Creating electricity from snowfall and making hydrogen cars affordable

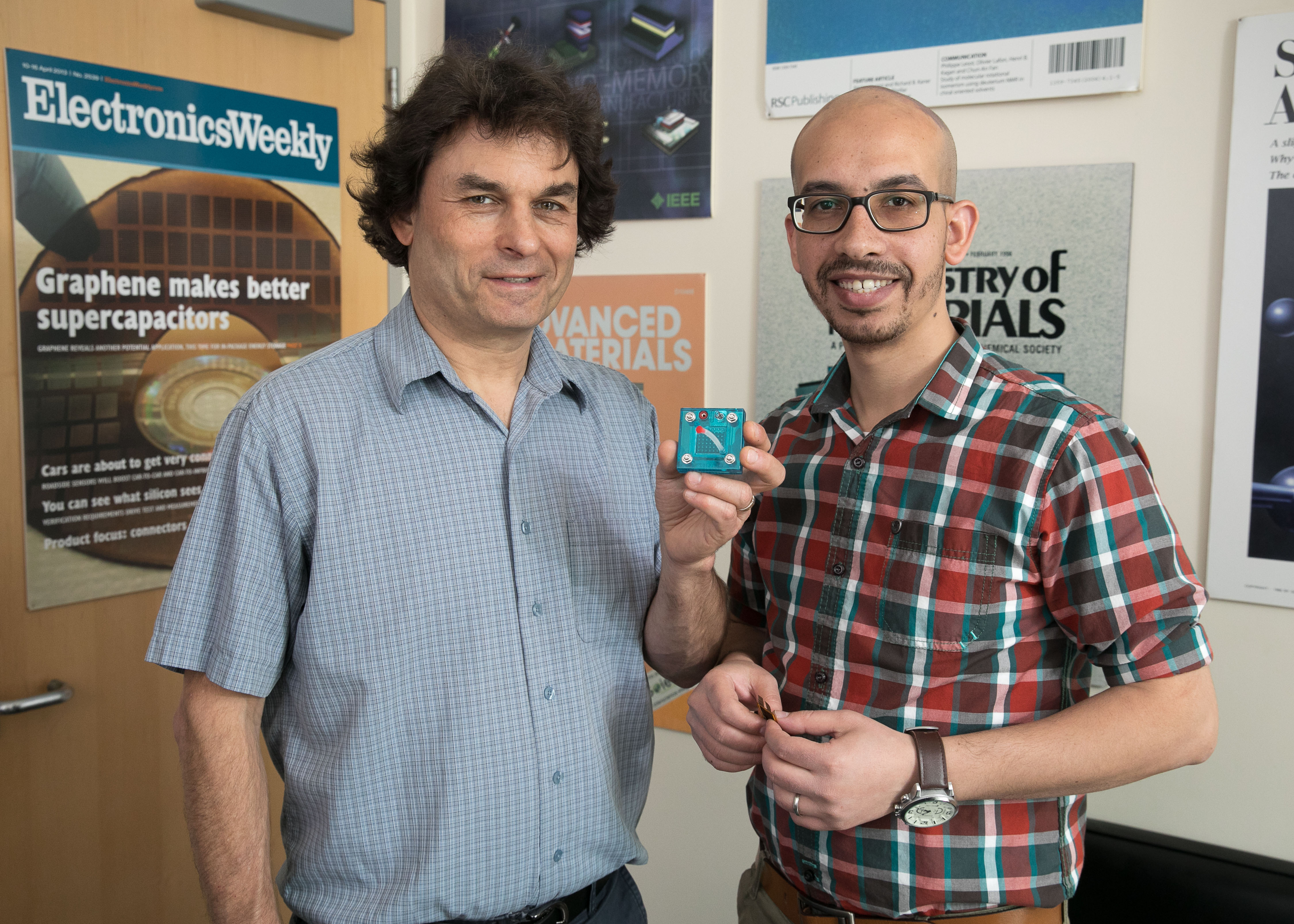

Richard Kaner, with Maher El-Kady, holding a replica of an energy storage and conversion device the pair developed. Photo credit: Reed Hutchinson

Professor Richard Kaner and researcher Maher El-Kady have designed a series of remarkable devices. Their newest one creates electricity from falling snow. The first of its kind, this device is inexpensive, small, thin and flexible like a sheet of plastic.

“The device can work in remote areas because it provides its own power and does not need batteries,” said Kaner, the senior author who holds the Dr. Myung Ki Hong Endowed Chair in Materials Innovation.“It’s a very clever device — a weather station that can tell you how much snow is falling, the direction the snow is falling and the direction and speed of the wind.”

The researchers call it a snow-based triboelectric nanogenerator, or snow TENG. Findings about the device are published in the journal Nano Energy.

The device generates charge through static electricity. Static electricity occurs when you rub fur and a piece of nylon together and create a spark, or when you rub your feet on a carpet and touch a doorknob.

“Static electricity occurs from the interaction of one material that captures electrons and another that gives up electrons,” said Kaner, who is also a distinguished professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and of materials science and engineering, and a member of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. “You separate the charges and create electricity out of essentially nothing.”

Snow is positively charged and gives up electrons. Silicone — a synthetic rubber-like material that is composed of silicon atoms and oxygen atoms, combined with carbon, hydrogen and other elements — is negatively charged. When falling snow contacts the surface of silicone, that produces a charge that the device captures, creating electricity.

“Snow is already charged, so we thought, why not bring another material with the opposite charge and extract the charge to create electricity?” said El-Kady, assistant researcher of chemistry and biochemistry.

“After testing a large number of materials including aluminum foils and Teflon, we found that silicone produces more charge than any other material,” he said.

Approximately 30 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by snow each winter, El-Kady noted, during which time solar panels often fail to operate. The accumulation of snow reduces the amount of sunlight that reaches the solar array, limiting their power output and rendering them less effective. The new device could be integrated into solar panels to provide a continuous power supply when it snows.

The device can be used for monitoring winter sports, such as skiing, to more precisely assess and improve an athlete’s performance when running, walking or jumping, Kaner said. It could usher in a new generation of self-powered wearable devices for tracking athletes and their performances. It can also send signals, indicating whether a person is moving.

The research team used 3-D printing to design the device, which has a layer of silicone and an electrode to capture the charge. The team believes the device could be produced at low cost given “the ease of fabrication and the availability of silicone,” Kaner said.

New device can create and store energy

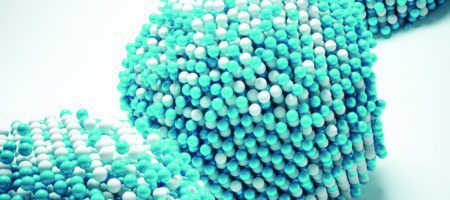

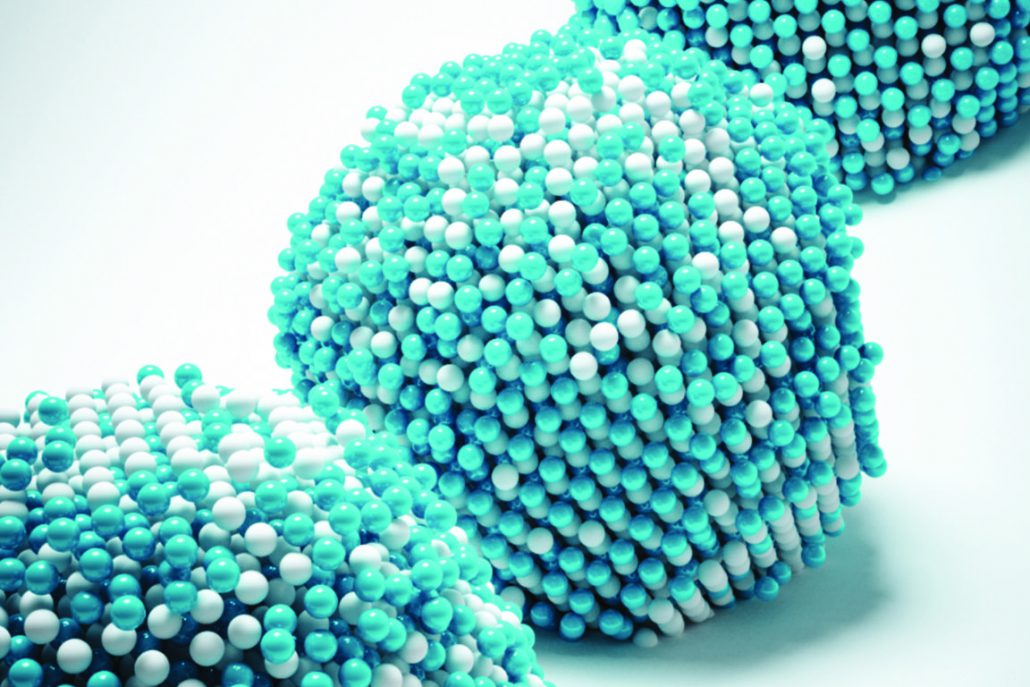

Kaner, El-Kady and colleagues designed a device in 2017 that can use solar energy to inexpensively and efficiently create and store energy, which could be used to power electronic devices, and to create hydrogen fuel for eco-friendly cars.

The device could make hydrogen cars affordable for many more consumers because it produces hydrogen using nickel, iron and cobalt — elements that are much more abundant and less expensive than the platinum and other precious metals that are currently used to produce hydrogen fuel.

“Hydrogen is a great fuel for vehicles: It is the cleanest fuel known, it’s cheap and it puts no pollutants into the air — just water,” Kaner said. “And this could dramatically lower the cost of hydrogen cars.”

The technology could be part of a solution for large cities that need ways to store surplus electricity from their electrical grids. “If you could convert electricity to hydrogen, you could store it indefinitely,” Kaner said.

Kaner is among the world’s most influential and highly cited scientific researchers. He has also been selected as the recipient of the American Institute of Chemists 2019 Chemical Pioneer Award, which honors chemists and chemical engineers who have made outstanding contributions that advance the science of chemistry or greatly impact the chemical profession.

Co-authors on the snow TENG work include Abdelsalam Ahmed, who conducted the research while completing his Ph.D. at the University of Toronto, and Islam Hassan and Ravi Selvaganapathy at Canada’s McMaster University, as well as James Rusling, who is the Paul Krenicki professor of chemistry at the University of Connecticut, and his research team.

More devices designed to solve pressing problems

Last year, Kaner and El-Kady published research on their design of the first fire-retardant, self-extinguishing motion sensor and power generator, which could be embedded in shoes or clothing worn by firefighters and others who work in harsh environments.

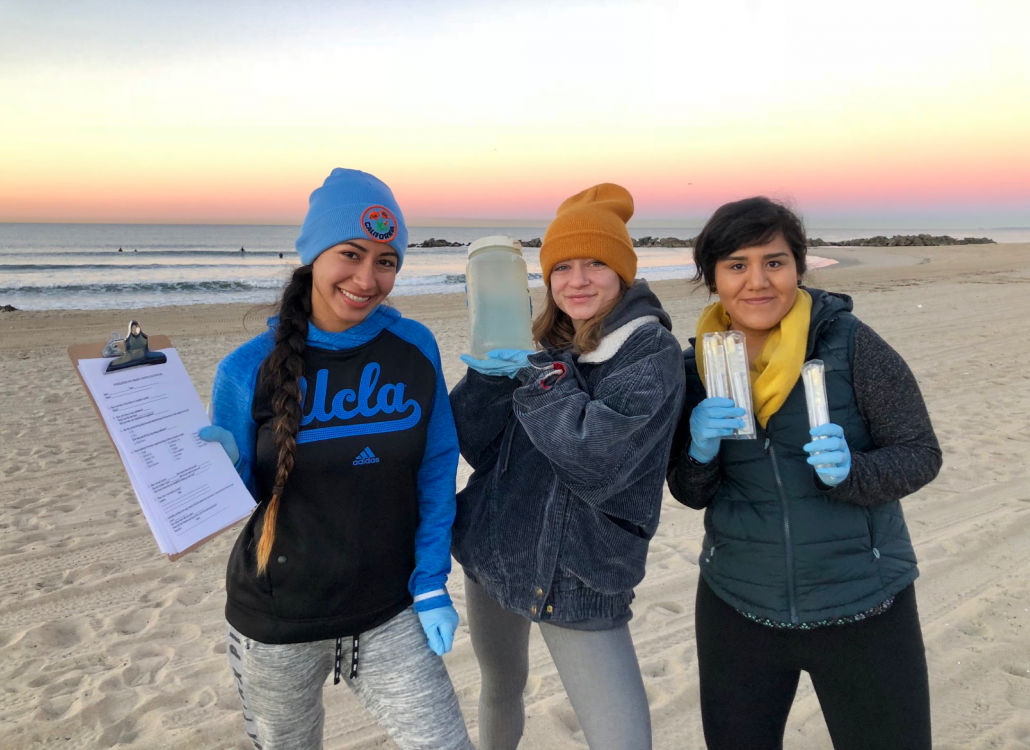

Kaner’s lab produced a separation membrane that separates oil from water and cleans up the debris left by oil fracking. The separation membrane is currently in more than 100 oil installations worldwide. Kaner conducted this work with Eric Hoek, professor of civil and environmental engineering.