What wolves’ teeth reveal about their lives

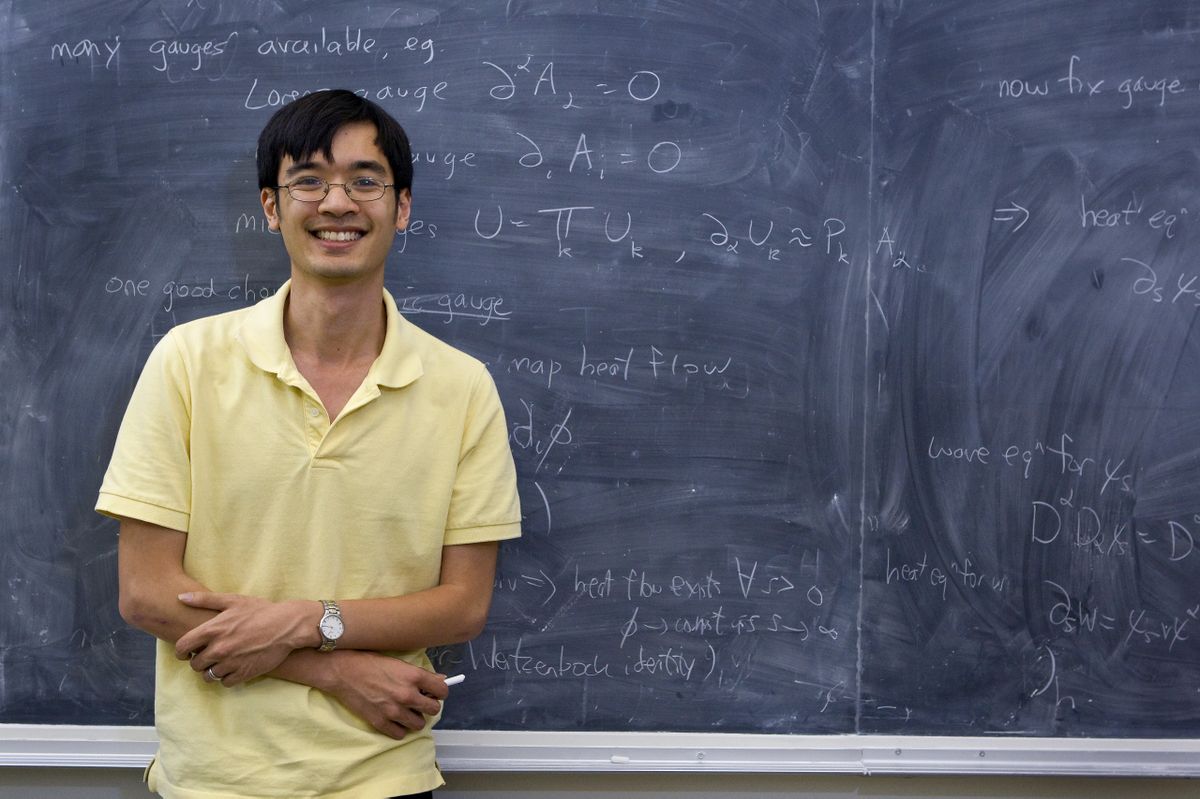

Biologist Blaire Van Valkenburgh has spent more than three decades studying the skulls of large carnivores. Here she displays a replica of a saber-toothed cat skull. At left are the skulls of a spotted hyena (in white) and a dire wolf (the black skull). Photo credit: Christelle Snow/UCLA.

UCLA evolutionary biologist Blaire Van Valkenburgh has spent more than three decades studying the skulls of many species of large carnivores — including wolves, lions and tigers — that lived from 50,000 years ago to the present. She reports today in the journal eLife the answer to a puzzling question.

Essential to the survival of these carnivores is their teeth, which are used for securing their prey and chewing it, yet large numbers of these animals have broken teeth. Why is that, and what can we learn from it?

In the research, Van Valkenburgh reports a strong link between an increase in broken teeth and a decline in the amount of available food, as large carnivores work harder to catch dwindling numbers of prey, and eat more of it, down to the bones.

“Broken teeth cannot heal, so most of the time, carnivores are not going to chew on bones and risk breaking their teeth unless they have to,” said Van Valkenburgh, a UCLA distinguished professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, who holds the Donald R. Dickey Chair in Vertebrate Biology.

For the new research, Van Valkenburgh studied the skulls of gray wolves — 160 skulls of adult wolves housed in the Yellowstone Heritage and Research Center in Montana; 64 adult wolf skulls from Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior that are housed at Michigan Technological University; and 94 skulls from Scandinavia, collected between 1998 and 2010, housed in the Swedish Royal Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. She compared these with the skulls of 223 wolves that died between 1874 and 1952, from Alaska, Texas, New Mexico, Idaho and Canada.

Yellowstone had no wolves, Van Valkenburgh said, between the 1920s and 1995, when 31 gray wolves were brought to the national park from British Columbia. About 100 wolves have lived in Yellowstone for more than a decade, she said.

In Yellowstone, more than 90% of the wolves’ prey are elk. The ratio of elk to wolves has declined sharply, from more than 600-to-1 when wolves were brought back to the national park to about 100-to-1 more recently.

In the first 10 years after the reintroduction, the wolves did not break their teeth much and did not eat the elk completely, Van Valkenburgh reports. In the following 10 years, as the number of elk declined, the wolves ate more of the elk’s body, and the number of broken teeth doubled, including the larger teeth wolves use when hunting and chewing.

The pattern was similar in the island park of Isle Royale. There, the wolves’ prey are primarily adult moose, but moose numbers are low and their large size makes them difficult to capture and kill. Isle Royale wolves had high frequencies of broken and heavily worn teeth, reflecting the fact that they consumed about 90% of the bodies of the moose they killed.

Scandinavian wolves presented a different story. The ratio of moose to wolves is nearly 500-to-1 in Scandinavia and only 55-to-1 in Isle Royale, and, consistent with Van Valkenburgh’s hypothesis, Scandinavian wolves consumed less of the moose they killed (about 70%) than Isle Royale wolves. Van Valkenburgh did not find many broken teeth among the Scandinavian wolves. “The wolves could find moose easily, not eat the bones, and move on,” she said.

Van Valkenburgh believes her findings apply beyond gray wolves, which are well-studied, to other large carnivores, such as lions, tigers and bears.

Extremely high rates of broken teeth have been recorded for large carnivores — such as lions, dire wolves and saber-toothed cats — from the Pleistocene epoch, dating back tens of thousands of years, compared with their modern counterparts, Van Valkenburgh said. Rates of broken teeth from animals at the La Brea Tar Pits were two to four times higher than in modern animals, she and colleagues reported in the journal Science in the 1990s.

“Our new study suggests that the cause of this tooth fracture may have been more intense competition for food in the past than in present large carnivore communities,” Van Valkenburgh said.

She and colleagues reported in 2015 that violent attacks by packs of some of the world’s largest carnivores — including lions much larger than those of today and saber-toothed cats — went a long way toward shaping ecosystems during the Pleistocene.

In a 2016 article in the journal BioScience, Van Valkenburgh and more than 40 other wildlife experts wrote that preventing the extinction of lions, tigers, wolves, bears, elephants and the world’s other largest mammals will require bold political action and financial commitments from nations worldwide.

Discussing the new study, she said, “We want to understand the factors that increase mortality in large carnivores that, in many cases, are near extinction. Getting good information on that is difficult. Studying tooth fracture is one way to do so, and can reveal changing levels of food stress in big carnivores.”

Co-authors are Rolf Peterson and John Vucetich, professors of forest resources and environmental science at Michigan Technological University; and Douglas Smith and Daniel Stahler, wildlife biologists with the National Park Service.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and National Park Service.

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.