The parallels of female power in ancient Egypt and modern times

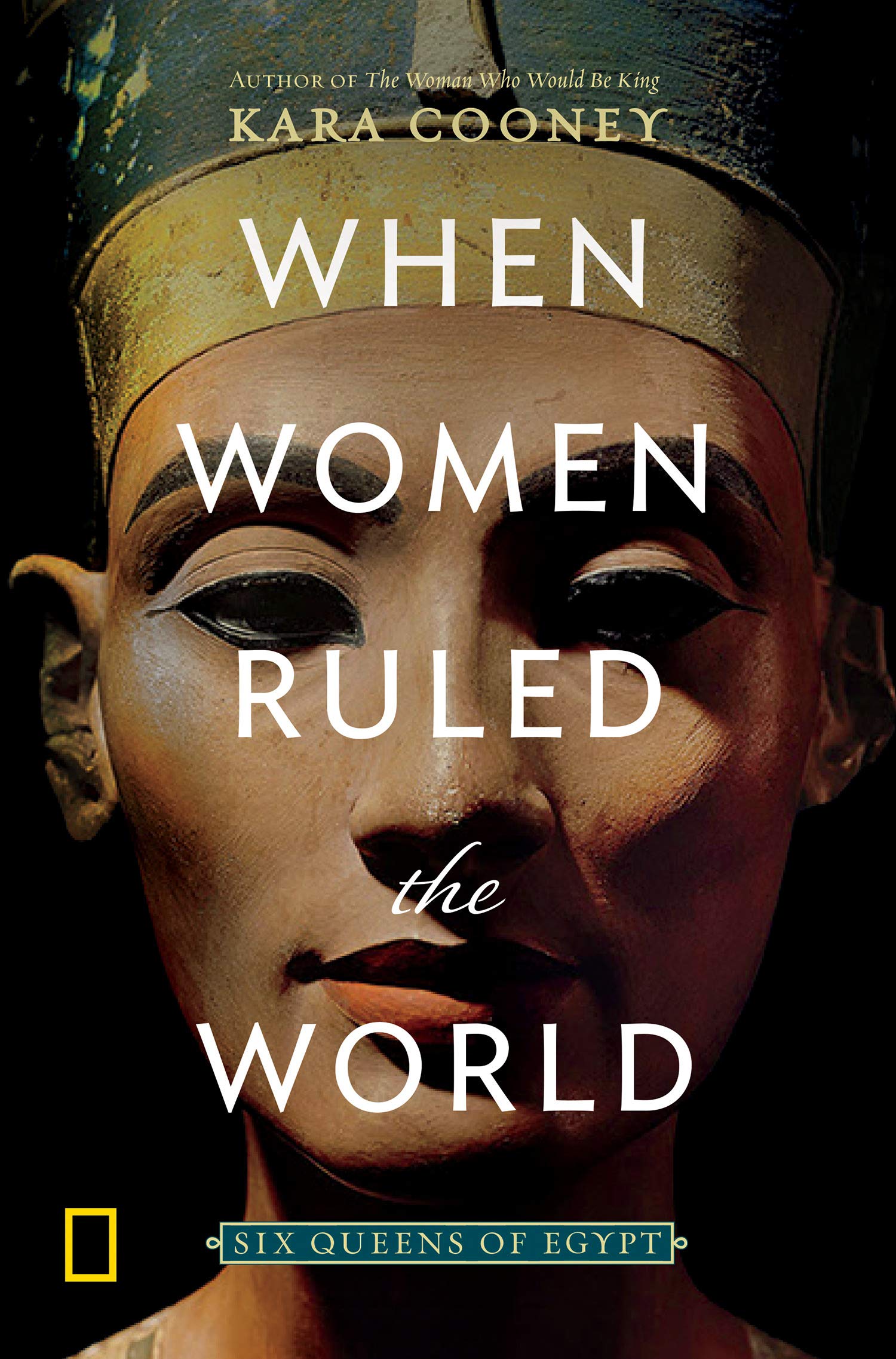

Kara Cooney, professor of Egyptian art and architecture at UCLA.

Over the course of 3,000 years of Egypt’s history, six women ascended to become female kings of the fertile land and sit atop its authoritarian power structure. Several ruled only briefly, and only as the last option in their respective failing family line. Nearly all of them achieved power under the auspices of attempting to protect the throne for the next male in line. Their tenures prevented civil wars among the widely interbred families of social elites. They inherited famines and economic disasters. With the exception of Cleopatra, most remain a mystery to the world at large, their names unpronounceable, their personal thoughts and inner lives unrecorded, their deeds and images often erased by the male kings that followed, especially if the women were successful.

In her latest National Geographic book, “When Women Ruled the World” Kara Cooney, professor of Egyptian art and architecture and chair of the UCLA Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, tells the stories of these six women: Merneith (some time between 3000–2890 B.C.), Neferusobek (1777–1773 B.C.), Hatsepshut (1473–1458 B.C.), Nefertiti (1338–1336 B.C.), Tawroset (1188–1186 B.C.) and Cleopatra (51–30 B.C.).

As we ponder Women’s History Month, and look forward toward a U.S. presidential primary campaign that includes more women candidates than ever before, we asked Cooney about themes of female power and what Egypt can illuminate for us.

Your book illustrates that Egyptian society valued and embraced women’s rule when it was deemed necessary, but these are not instances of feminism. Their attempts to rule was really about keeping the set structure in place.

Studying Egypt is a study of power, and specifically of how to maintain the power of the one over the many. That story also always includes examples of how women are used as tools to make sure the authoritarian regime flourishes. This is the most interesting part to me because then the whole tragedy of the study, of the book, is that this is not about feminism at all. It’s not about feminists moving forward, it’s not about the feminist agenda. It’s not about anything but protecting the status quo, the rich staying rich, the patriarchy staying in charge and the system continuing. We still do this, us women. Women work for the patriarchy without thinking about it, all the time. In the end, did women rule the world? Yes, they did rule the world but did it change anything? No.

I want to look at our world the same way. It doesn’t matter if we have a female president. What matters is how people rule and whose agendas are served.

People who have been to Egypt probably know the name Hatshepsut and maybe Nefertiti, but clearly the most pervasive female cultural Egyptian reference is Cleopatra. Why is she the one? Do we just have more materials related to her?

No, it’s because when you are successful, you can very easily be erased. Cleopatra failed in her efforts to hold on to power and hold onto native rule in Egypt. When you are a failure, it’s aberrant, strange and it spins a good tale. It’s a great story, failure. Whereas success is doing what everyone did before you and what everyone will do after you. It’s the same and nobody cares. It’s the same as being a successful female in a meeting or a successful female who shares a great idea with her boss and her boss takes that idea into the meeting while she sits there meekly, letting the boss take it for his or her own because it’s a successful, great idea.

So it’s the women who are the greatest successes in the story who are the most successfully erased. The women who did it all wrong and didn’t leave their land better than when they found it, who are remembered as cautionary tales. That’s our cultural memory. That’s why everyone can pronounce the name Cleopatra and no one has any idea how to pronounce Hatshepsut. She is not in our cultural memory. It doesn’t serve our patriarchal system to add her to it.

But remember, in the Egyptian mindset Cleopatra wasn’t a failure. She fought Rome and lost, but in the Arabic sources Cleopatra is remembered as an adherent to Egyptian philosophy, a freedom fighter against Rome and as a learned patriot to her people.

How does the framework of Egypt’s long and relatively well-documented history and culture inform our perspectives on power as American citizens, a country of such a comparatively short history and governance?

Egypt is such a gift. When I get asked — and I do — “Why bother devoting your life to this place that’s been gone for 2,000 years and studying people that are as old as 5,000 years?” the answer is that Egypt provides me with 3,000 years of the same cultural system, religious system, government system and language system. I can follow them through booms and busts, through collapse and resurgence and see human reactions to prosperity and pain. That’s really useful. We are in this infancy of 250 years and we think we are so smart, we think we are post-racial, post-sexist and all of these things. But we’re not. Egypt is a huge gift to compare the situation that you are in to the past to see how you might better face the future.

It must be difficult to unearth women’s stories because of the ways in which historical records from around the world largely excluded information about them.

That’s the frustration of working with Egypt. We can’t forget that this is an authoritarian regime. It’s not a competitive place where I can get a speech from a competitor and try to understand a different viewpoint and agenda. It’s my responsibility as a historian of this regime to try and break it down and see what the truth is between the lines. For these women in power it’s even harder because so many of them were erased when their stories did not fit the patriarchal narrative. My job is to be a historical reconstructionist without being a revisionist. I’m interested in seeing how people work within a system and why we are so opposed, even hostile, to female power.

Why are we so hostile to female power?

The stereotype is that the female is going to use emotionality, her own and others, to manipulate and lie, to shame and guilt people into doing something. The man somehow won’t do that. He will be a straight shooter.

There is the idea that there is the masculine emotionality and a female emotionality. This female emotionality, which many men also bear, is the reason we don’t allow them to wield power because they’re happy, sad, up, down. They feel too many emotions that cannot be allowed.

The men that we ask to lead must suppress those emotions and show this even-keeled strength or only anger and no other softer emotions and then only strategically. We demand a kind of emotionality from our leaders that I find quite stunted and I want to know what the evolutionary biology of that is because a lot of this is a knee-jerk reaction to what serves us better in a short-term, acute time of crisis. I think we all need to discuss what it is about that female emotionality, of connecting with our own emotions and others or even manipulating our emotions for our own gain, that is so problematic.

As of now, six women have announced Democratic presidential campaigns for 2020. What does our historical knowledge of what happens to women when they seek power bode for the coming election season?

I get rather cynical about it, to be honest. Already I see the dialogue revolving around deceit and not being a straight shooter.

Again, it’s that double standard that you wouldn’t necessarily get with a man. It’s interesting to see how people are judging women based on emotionality and how much of that they show, how ambitious they seem to be and how duplicitous they may or may not be.

That possibility for deceit is something we are quite obsessed with for female candidates. The possibility of lies by the female is that much more powerful than the outright, absolute fact of deceit by a male candidate or leader. That is very interesting to me. The female is assumed to be a liar, but when a man lies he’s doing it for a reason and he’s on my side so I’m cool with it.

We’ve been discussing racism for some time but we do not discuss our hostility towards females in power. Unless we start to talk about it and openly discuss it, it won’t change.