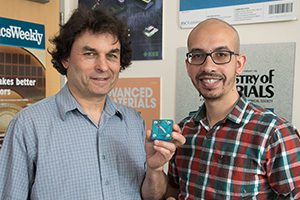

Monica Smith. Photo credit: Paul Connor

The only thing a person really needs to be an archaeologist is a good sense of observation, UCLA professor of anthropology Monica Smith proclaims in her most recent book, “Cities: The First 6,000 Years.”

Advanced degrees and research experience are useful of course, but successful fieldwork is rooted in “noticing,” she said.

Archaeologists are always looking down noticing traces of what’s been left behind, and the stories detritus can tell, she said. These days at UCLA that might mean traces of glitter bombs launched by graduates during the last several weeks.

“We walk along and there’s all this glitter on the ground, and even though it gets cleaned away, you can never get it all so then you start to see little traces of glitter everywhere, because people are tracking it on their shoes all around campus,” Smith said. “We’re not only walking through an archaeological site, we’re making one.”

Smith is amused at the thought of future archaeologists encountering and interpreting the meaning behind those trace elements of shimmer in the dust around this particular area in one of Earth’s largest cities.

In vivid style, Smith’s latest book examines ways in which human civilization has organized itself into city life during the last 6,000 years, a relatively short time span in the grand scheme of human existence. Today, more than half of the world’s population resides in cities, and that number will continue to grow. But that wasn’t always so.

In “Cities,” Smith tracks the ways metropolitan hubs in different parts of the world emerged unrelated to one another, but in eerily similar forms, revealing the inherent similarities of humans’ needs regardless of what part of the world their civilization evolved.

“I started asking myself, ‘Why do these places all look the same even though they’re different times, different areas, different cultures and different languages?’” she said. “What is it about our human cognitive capacity that leads us to have the same form over and over and over again?”

She imagines how the first Spanish warriors to arrive in Cuzco in Peru, or Tenochtitlan in present day Mexico City, encountered the layout of ancient Inca and A

ztec cities, with shops and open squares and marketplaces resembling what they would see at home — despite the cultures never having had contact before.

“The similarities suggest that humans developed cities because it was the only way for a large number of people to live together in a single place where they could all get something new they wanted, whether that was a job, entertainment, medical care or education,” Smith said.

For the purposes of her analysis, Smith defines a city as a place with a dense population of multiple ethnicities; a diverse economy with an abundant variety of readily available goods; buildings and spaces of religion or ritual; a vertical building landscape that encompasses residential homes, courts, schools and government offices; formal entertainment venues; open grounds and multipurpose spaces; broad avenues and thoroughfares for movement.

Before cities, the human population was scattered across larger agrarian swaths, with families having everything they needed to survive in their own homes. People would come together for trading festivals or sacred ceremonies. These most likely began to last longer and longer, Smith said, creating a permanent collective settlement around places conducive to providing food, water, shelter and entertainment. Humans essentially took the bold step of living away from their immediate food supply to live in cities among larger groups of other humans.

Takeout food vendors have been a staple of cities stretching about as far back as you can get, with evidence of takeout food in ancient cities like Pompeii and Angkor, Smith notes in her book.

And cities allowed for the evolution of all kinds of new jobs and enterprises — bookkeeping, the service industry and managers — constituting a newly emergent middle class that found new opportunities to thrive in dense populations.

Some aspects of city life accelerated long-standing tendencies. Humans are a unique species in the animal kingdom due to our deep dependence on objects, a fact that aids archeologists in their work of noticing. Ancient cities also struggled with some of the same things we do in modern times — trash for example, Smith said.

“We think of ourselves as bad modern people because we have all this trash,” Smith said. “But everyone everywhere has trash. Ancient cities are full of trash. Modern cities are full of trash because people want more stuff.”

Archaeologists are obsessed with trash, Smith said. They learn much and encounter new questions from what was considered disposable to our ancestors.

Smith’s book also offers a descriptive window into day-to-day life on an archaeological dig, sharing challenges and the excitement of new technologies that help identify potential dig sites. People working to excavate subway tunnels and building foundations in modern Athens, Rome, Mexico City, Istanbul, Paris and other places are constantly finding new evidence of these metropolises’ earliest incarnations.

Much like current generations of young adults and children who cannot imagine a world without the internet, cities are here to stay, Smith said.

“From this point forward, there is no way that humans can live without urbanism, there is no ‘going back to the land,’” she said. “We can take a sort of comfort in the fact that the challenges we face like infrastructure, transportation, water sourcing, pollution and trash have essentially been a part of city life from the very beginning.”

Smith said one of the goals of her writing is to inspire people to think of cities as dynamic and adaptable.

“We can work to make cities not only more efficient, but more equitable, in the sense of social justice and greater opportunities for larger numbers of people, along with greater diversity,” she said. “Cities are not just inherited configurations, but are places with potential for growing into the better societies that we wish for ourselves and others.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.