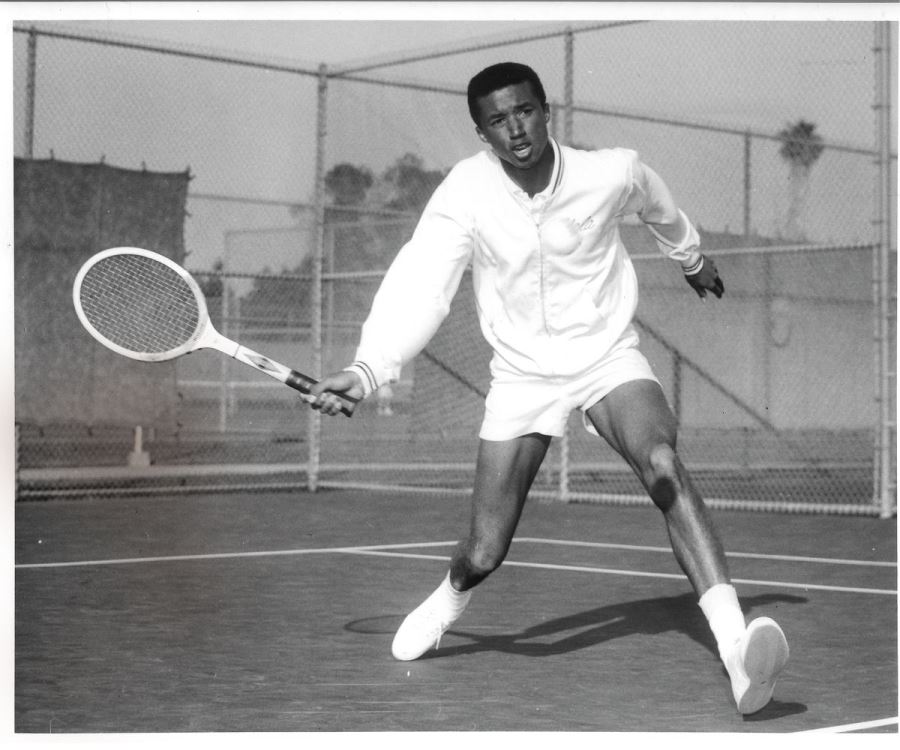

Fifty-one years ago, Arthur Ashe became the first (and last) African American man to win the U.S. Open, which begins tomorrow. As is fitting, last year the tennis community celebrated this remarkable achievement. This year, however, marks a 50-year milestone that likely meant much more to Ashe, and has truly shaped America’s communities with a positive and lasting effect that extends far beyond the sport of tennis, yet has received far less attention.

If we are looking to impact, and the ability to make a difference for young people from families of modest means, Ashe’s most meaningful contribution to the world – and there were many – arguably came as a result of a partnership with his fellow UCLA alum, Charles “Charlie” Pasarell and Sheridan “Sherry” Snyder (UVA) in the form of the National Junior Tennis League, now National Junior Tennis and Learning.

The three friends and accomplished athletes decided 50 years ago that the sport of tennis deserved the presence and participation of all Americans, including those who didn’t belong to country clubs or with the means to travel or hire coaches, all the accoutrements of success desirable in those days, and the result was the establishment of the NJTL. Ashe insisted that the organization be more than about bringing the talent of the inner city to tennis courts; he advocated for the creation of academic support programs for each chapter. This was idea was transformative.

Building the NJTL was not an easy feat – the founders had to convince the mayors of cities to endorse using their tennis courts for this programming. They convinced companies like Coca-Cola, Chase and many others to become financial sponsors. The friends diligently recruited competent coaches willing to work for a pittance with young people less privileged than those they may have coached in the past. Children of color had to be encouraged to see themselves as tennis players. To its credit, in 1985 the United States Tennis Association (USTA) took over the administration of NJTL, but Ashe, Pasarell and Snyder remained, as we say today, “all in.”

One of Ashe’s protégés shared with me the story of having Ashe himself watch him play tennis when he was a young man. As a black college student, he hoped tennis would be his ticket to success. Ashe watched him play several times and several times the tennis phenom couched his assessment that while the young man would be a good tennis player, he didn’t have the skill set to thrive at the professional level by saying, “So you are keeping up your grade point average, right?” The protégée took the hint, kept his GPA high and with that coaching, became a successful business man who now keeps up his tennis game at the country club where he holds a membership. This of course, is just one small example of Ashe’s personal impact.

To be sure, it is challenging to single out which of Arthur Ashe’s many accomplishments is the most significant. Because I teach a focused freshman seminar called Fiat Lux on Arthur Ashe and oversee the Arthur Ashe Legacy Fund at UCLA, I am often asked to weigh in on what he should be most remembered for. Given what he packed in during his 49-year life, this is a bit of a fool’s errand. After all, his tennis accomplishments are etched in the record books—in addition to the U.S. Open, he was the first (and last) African American male to win the finals at Wimbledon (1975).

But aside from his well-known successes on the court, off the court he was never still. He was a quiet but effective friend to the Civil Rights movement in the United States and became an ardent and respected advocate for the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. His commitment to social justice causes was life-long; within months of his death he was arrested for protesting what he had concluded was the unfair treatment of Haitian immigrants.

When Ashe was afflicted with heart disease in his mid-30s, he agreed to tell his story for the American Heart Association as part of its campaign to encourage Americans to know the warning signs of cardiac disease. While such a public proclamation seems tame today, in the 1970s, there was significant reputational risk in letting the public know of his weakened condition. His HIV-AIDS diagnosis in 1988 coincided with the dark early days when the disease and those who suffered from it endured enormous and often intractable stigma. While he didn’t immediately go public with his situation, once he did, he was all in as a spokesperson for research and fair treatment for sufferers. Prior to his death and thanks to the tireless efforts of his wife following it, millions of dollars were secured for research.

And yet, according to the many members of the NJTL community that are celebrating this 50-year anniversary, Ashe was to the very last devoted to the cause of raising up young people in diverse communities. He was as willing to run drills with and coach during the first years of the program, when he was a tennis star himself, as he was in the last summers of his life, when he was afflicted with HIV.

No male African American has surpassed Ashe’s tennis achievements—a dispiriting fact that would sadden him profoundly. But his other legacy, off the court, is just as compelling, if not more so, than his profound achievements as an athlete. It is not an exaggeration to say that because of the shared passion and unflagging engagement of Ashe, Pasarell and Snyder, tens of thousands of young people from New York, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Los Angeles and other cities went from their playgrounds to college to positions and lifestyles commensurate with their highest goals.

Ashe never stopped championing equality and community through the NJTL – a remarkable legacy that has resounding and relevant impact even today.

Patricia Turner is senior dean of the UCLA College, and dean and vice provost of UCLA’s Division of Undergraduate Education. Turner is an expert in World Arts and Cultures and African-American Studies, and teaches a freshman seminar on Arthur Ashe’s significant accomplishments.