Study finds cultural differences in attitudes toward infidelity, jealousy

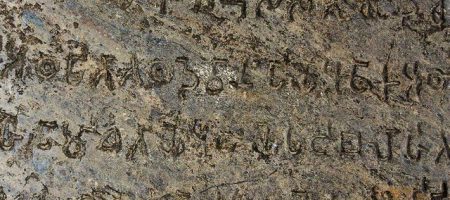

The 11 societies studied included the Namibian community of the Himba, where this father and child live. Photo credit: Brooke Scelza.

In cultures where fathers are highly invested in the care of their children, both men and women respond more negatively to the idea of infidelity, a cross-cultural study led by UCLA professor of anthropology Brooke Scelza found.

Jealousy is a well-examined human phenomenon that women and men often experience differently, but the study published this week in Nature Human Behavior also examined cultural differences in the experience of jealousy, by surveying 1,048 men and women from 11 societies on five continents.

Scelza wanted to use established evolutionary science to go beyond the idea that a phenomenon of human behavior is either universal or variable.

“In studying jealousy we find evidence for both,” she said. “Almost everywhere men tend to be more upset than women by sexual infidelity,” she said. “At the same time, cultural factors lead to population-level differences in how infidelity is viewed.”

For example, in places where men are not expected to be as involved in day-to-day care of children, people were less prone to jealousy. And in cultures that are more accepting of what Scelza describes as “concurrent” sexual relationships, responses to questions about jealousy were more muted.

The study harnessed expertise from a dozen researchers who have worked extensively in the populations surveyed. Eight were small-scale societies, including the Himba, a pastoral community in Namibia, and the Tismane, indigenous people of Bolivia. Three populations of respondents were from urban settings, such as Los Angeles, India and Okinawa, Japan.

Researchers used a five-point scale to determine attitudes about infidelity and jealousy.

“Very few people of either sex said that either sexual or emotional infidelity was ‘very good’ but responses of ‘OK’ and ‘good’ were not uncommon,” Scelza said. “What is most interesting is that we were able to not just show that cross-cultural variation in jealous response exists, which by itself is not very surprising, but we were able to explain some of that variation using principles from evolutionary theory about the relative costs and benefits of infidelity, including how common extramarital sex is, and whether men are very involved in child-rearing.”

Another surprising finding of the study was that in the majority of populations studied, both men and women found sexual infidelity more upsetting than emotional infidelity. In only four of the populations, including Los Angeles and Okinawa, a majority of women responded that emotional infidelity was more upsetting. These responses echoed what women surveyed in smaller communities like the Himba and Tsimane reported to researchers — that sexual infidelity leads to fears of loss of paternal support and resources for children.

“Typically, we tend to think that emotional infidelity is more likely to lead to loss of resources, which is why it is thought to be more upsetting to women, but we found the opposite,” Scelza said.

This study is part of a growing body of work over the last decade from social scientists who seek to be more inclusive and not just focus their research on western, educated, industrial, rich and democratic — also known as WEIRD — societies, Scelza said.

“For a long time in psychology there was a tendency to use student samples from U.S. and European universities, and if they found a consistent result, extrapolate that as something that could be a ‘human universal,’” she said. “But there are many reasons to believe that people from WEIRD populations are unlikely to be representative of humanity more generally.”

For example, Scelza’s idea for the study was sparked by her ongoing work with Himba pastoralists living in rural Namibia. In her work on marital and family dynamics she found that both women and men frequently had multiple concurrent sexual partners but still experienced happy marriages.

“Over and over I was told that one could love both their husband and another man, and that in fact, many people would be uninterested in having a spouse who could not attract other partners,” she said. “It made me wonder whether or not people in this culture experienced jealousy at all. It turns out they do, but those findings inspired me to take a broader look at how jealousy is treated around the world, and try to understand where and why people view it differently.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.