‘Jump-starting’ the brain of a patient recovering from a coma

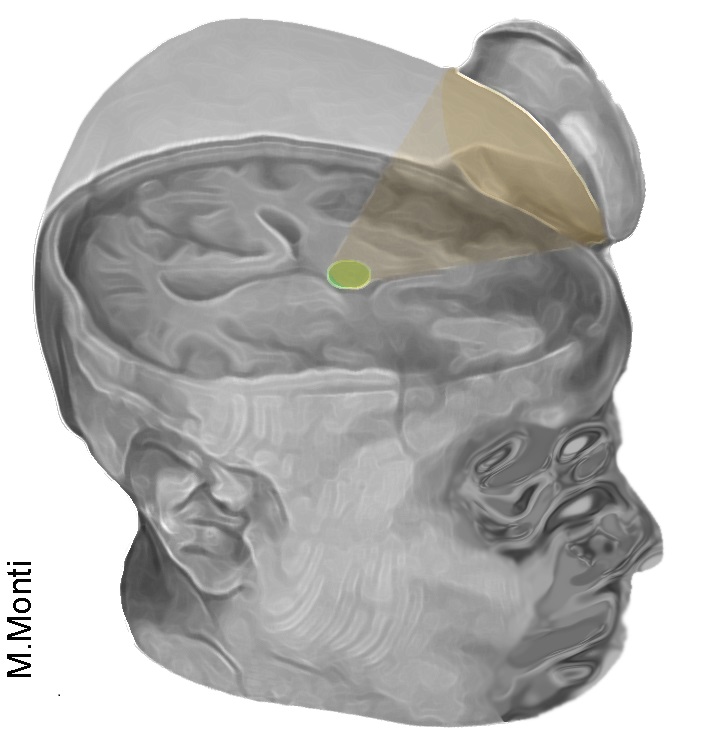

Image: Representation of ultrasonic stimulation of the brain’s thalamus in a post-comatose patient.

New noninvasive technique could result in low-cost therapy for patients with severe brain injury

By Stuart Wolpert

A 25-year-old man recovering from a coma has made remarkable progress following a treatment to “restart” his brain using ultrasounds, a team of UCLA scientists reported in a letter published in the journal Brain Stimulation. This is the first time such an approach to severe brain injury has been tried.

“Our technique uses sonic stimulation to excite the neurons in the thalamus – almost as if we were jump-starting them back into function,” said lead author Martin Monti, associate professor of psychology and neurosurgery. “Until now, the only way of achieving this was for a patient to undergo brain surgery and have electrodes implanted directly inside the thalamus – an egg-shaped structure which serves as the bustling central hub for information flow within the brain – a risky procedure known as deep brain stimulation. Our approach directly targets the thalamus, but is noninvasive.”

This new technique, called low intensity focused ultrasound pulsation (LIFUP), has been pioneered by co-author Alexander Bystritsky, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences in the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior and founder of Brainsonix, which provided the experimental device for this research. In this approach, a small device, about the size of a coffee cup saucer, is placed by the side of a patient’s head. The device creates a small sphere of acoustic energy that can be aimed at different regions of the brain to excite or inhibit brain tissue. Monti said the technique is quite safe, partly because the amount of energy from each stimulation is small. The researchers repeated it 10 times over 10 minutes.

The changes in the patient’s brain were remarkable, Monti said. Before sonic stimulation, the patient could show only minimal signs of being conscious and of understanding speech. By the day after the sonic stimulation, he was able to show greater responses and started vocalizing responses. Three days later, the patient was fully conscious, had regained full language comprehension, could reliably communicate by gesturing “yes” or “no” with his head, and even gave a fist-bump.

“This result is exactly what we expected,” Monti said.

However, he cautioned that this is only one patient. “It is possible that we were just very lucky and happened to have stimulated the patient just as he

was spontaneously recovering,” Monti said. “This is why it is so crucial, before we get too excited, that we repeat this procedure in more patients.”

Joining with Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center

Monti and his colleagues, under the direction of UCLA professor Paul Vespa, are planning to perform this procedure in several more patients at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, working with UCLA’s Brain Injury Research Center, and with funding from the Dana Foundation and the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation.

If the researchers are able to demonstrate that the recovery in this patient was linked to the ultrasound stimulation, the potential for this technique could be very large. There are currently few effective treatment options for patients in a coma, Monti said.

Monti’s long-term goal is to one day be able to build a small portable device, perhaps a helmet, that could be brought to the bedside of a patient who is in a coma and, with no surgery, help the brain return to normal levels of function, leading to the return of cognitive functions and consciousness.

Hope for an entirely new treatment

Monti said he hopes his technique could be the beginning of a new noninvasive, low-cost therapy to help wake up patients in a coma — perhaps even patients in a vegetative state and in a minimally conscious state, for whom there is almost no effective treatment.

The idea behind this new approach is that when patients fail to fully recover from a coma, and awaken to a state of deeply impaired mental function, this is due partly to an impairment in the functioning of the thalamus. Pharmacological treatment targets the thalamus only indirectly.

Co-authors are Vespa, who holds UCLA’s Gary L. Brinderson Family Chair in Neurocritical Care, and is a professor of neurology and neurosurgery at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, and director of neurocritical care at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center; Caroline Schnakers, a UCLA researcher in neurosurgery; Bystritsky; and Alexander Korb, a researcher in the Semel Institute.

Meet the Professor- In his own words

Meet the Professor- In his own words

By Martin Monti

In my laboratory we focus on two of the most fundamental aspects of being human:

1. What is the relationship between language and thought?

Does language make us special? One of the most striking features of human cognition is the ability to generate an infinite number of ideas by combining a finite set of elements according to structure-dependent principles. This ability is most clearly displayed in language, but also characterizes other aspects of our cognition such as drawing inferences, performing mental arithmetic or music cognition. Does language enable other types of structure-dependent cognition? Does the structure of natural language provide a scaffolding on which to build other forms of high-level cognition? In my research I employ behavioral and fMRI tools in healthy volunteers and patients to address these questions.

2. How is consciousness lost and recovered after severe brain injury?

How do we ever know that someone, other than ourselves, is conscious? Philosophical considerations aside, this issue is at the heart of one of the most challenging and least understood conditions of the human brain: the Vegetative State. This is a condition in which, after severe brain injury, patients are awake but not aware. In my research I focus on brain processing and consciousness in these patients, to try to ameliorate diagnostic procedures and to develop new interventions that may help recovery.

Watch it here Professor Monti on “The Mystery of Consciousness and the Vegetative State” at TEDx Claremont Colleges