LOS ANGELES HOUSING CRISIS REMAINS CRITICAL WITH THE DEFEAT OF PROPOSITION 10

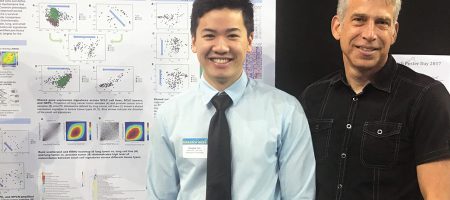

The new report documents decades of the city’s rent control policy, including the introduction of a rent stabilization ordinance in the 1970s. Pictured: A 1978 rent control march on City Hall.

By Jessica Wolf

California voters rejected Proposition 10, which would have repealed the Costa-Hawkins act of 1995 and allowed cities across the state to implement broader rent control policies as a response to California’s current affordable housing crisis.

It’s an issue that the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy tackled in its first major publication since the center’s founding in 2017. The paper, titled People Simply Cannot Pay the Rent, was released well before Election Day in an effort to inspire dialogue around and contextualize the history of rent control in Los Angeles. It also presented several options (including the repeal of Costa-Hawkins) that could help ameliorate the economic vulnerability and anxiety of the growing number of people who cannot afford rent in Los Angeles.

The center’s mission is to bring historical perspective to contemporary policy issues, and UCLA researchers will continue to push for meaningful policy decisions when it comes to this crisis.

“The defeat of Prop. 10 does not solve the problem of affordable housing,” said David Myers, a professor of history and the center’s director. “The logic of rent control as a valuable policy tool remains as valid as ever. This is what our working paper showed – that rent control can be an effective instrument to protect the most vulnerable residents of a city. We hope that it is read with growing interest as politicians and policy leaders continue to grapple with the acute housing crisis in California.”

Offering a historical perspective

Aimed at city and state officials, as well as concerned citizens, the report documents the history of rent control policy in Los Angeles from World War II through the present day, focusing on three important milestones: the implementation of federal rent controls during World War II; the introduction of the city’s current rent stabilization ordinance in response to high inflation in the 1970s; and today’s crisis.

Recent data indicate that Los Angeles residents face the nation’s largest rent burden, with median renters spending 47 percent of their income on rent. According to 2011 data, 57 percent of Los Angeles renters were considered “rent burdened,” up from 37 percent in 1980, when rent control was first established. The trend has also contributed to the region’s homelessness epidemic – approximately 53,000 people in Los Angeles County are homeless.

“Los Angeles is experiencing a perfect storm of affordable housing shortfalls, rising rents and dropping incomes,” Myers said. “It is crushing the poorest citizens of the city, particularly Latinos and blacks, with disproportionate force, and this interplay has exacerbated homelessness – the great social and moral scourge of our time, and an epidemic that threatens the life and soul of our city.”

The report also suggests that public engagement is critical. Options proposed include requiring landlords and tenants to sign property registration forms so that tenants are aware of their rights, and a public relations campaign that would cast the crisis as a serious social and public health problem. Both of those actions were undertaken by the federal government during World War II, the paper notes.

A contentious issue

“Nearly $100 million was spent to defeat Prop. 10, four or five times what the proponents spent,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, a former Los Angeles County supervisor, current senior fellow at the

center and author of the study’s introduction. “Money does make a difference. The legislature would be well-advised to pass legislation that removes some, if not all, of the shackles

that the Costa-Hawkins law places on local governments to address the affordable housing crisis. If they don’t, there will be another Initiative in 2020 to repeal the whole thing.”

The report’s author is Alisa Belinkoff Katz, fellow with the center and associate director of the LA Initiative, housed in UCLA’s Luskin School. Historical information was contributed by doctoral candidates Peter Chesney, Lindsay Alissa King and Marques Vestal.

During a campus panel conversation the center hosted leading up to the election, Ph.D. candidate Vestal said he thinks taking the historical long view can help depressurize the contentious issue.

Rent control policies date back to 1600s Rome when the Catholic Church imposed restrictions on Christian landlords who owned buildings in Jewish ghettos. Most countries in Europe immediately implemented rent control policies after World War II to benefit recovering economies, he pointed out.

“To an extent, housing crises are just a part of urban life,” he said. There is widespread agreement that more development is crucial to address Los Angeles’ current crisis, but even the most optimistic projections say it could take a decade to make a dent in that need, said state Assemblyman Richard Bloom.

“The issue is how to help those people who are suffering now and in this moment and over the next 10 years,” he said. “We can’t simply write them off and say this is a lost generation who will not have housing or who will have a lower quality of life. That’s the main reason I took on the Costa-Hawkins debate in the first place.”

Bloom was the first lawmaker to introduce legislation that would revise or repeal Costa-Hawkins. It died in committee. He thinks legislation is a more elegant solution than a ballot measure, and said he is certain there will be “folks banging on my door.”