UCLA graduate helps victims of Syrian war ‘rise again’

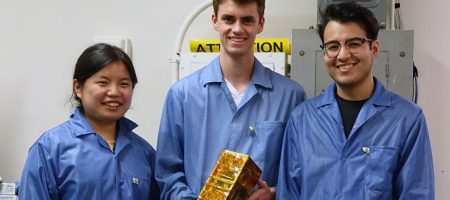

Through her non-profit, Haya Kaliounji has provided free prosthetic devices to more than 40 people who lost limbs in the Syrian civil war. Credit: Rebecca Kendall/UCLA

Haya Kaliounji’s nonprofit provides wounded people in her home country with free prosthetic limbs

When Haya Kaliounji thinks of Iron Man, she doesn’t envision the Marvel superhero. Instead she sees the 6-year-old boy who lost his legs after his home was struck by a missile as he played on his balcony.

“He was under the rubble and his mother was looking for him,” said Kaliounji, who will graduate from UCLA this week with a bachelor’s degree in physiological sciences. “I don’t think he was crying, she just saw his hair from under the rubble and they took him out.”

Today, he runs and plays like other kids and is healing psychologically and physically.

“His friends call him Iron Man,” she said.

It is children like him who were on her mind in 2015 when Kaliounji, a Syrian immigrant, founded Rise Again, a non-profit organization that provides free prosthetics to people — mostly children — who have been victims of violence during the ongoing war in Syria. It is their stories Kaliounji tells when she’s trying to raise money and awareness about the losses these children and their families have experienced and continue to experience.

When Rise Again started it was estimated that there were 40,000 people living with war-related amputations. That number is even larger now, Kaliounji said.

According to the World Bank, more than 400,000 people have been killed in Syria since the conflict began in 2011. In addition, 5 million have sought refuge in other countries, including thousands who have come to the United States. Another 6 million people have been displaced within Syria. And 540,000 people continue to live in areas under siege.

Rise Again began as a project designed to help Kaliounji earn her Gold Award, the most prestigious honor given by the Girl Scouts. Her goal was modest — to help three people.

Naim Maraashly, a well-known medical technician in Syria, remembers the day Kaliounji called him to tell him about her project.

“I didn’t really believe it,” said Marasshly, who produces the prosthetics and teaches the recipients how to walk and use their new limbs. “I told myself it would be for a recipient or two. But she surprised me with her work and dedication.”

Over the years Kaliounji has raised money for Rise Again by speaking to community groups, organizing fundraisers at St. Anne Melkite Catholic Cathedral in North Hollywood, and through a GoFundMe campaign, recycling drives and sales of hand-made crafts. One of her professors at Pasadena City College, which she attended prior to enrolling at UCLA, even wove Rise Again into a graded fundraising opportunity for her class.

During the past four years, Rise Again, with assistance from St. Anne’s, and Maraashly, have assessed, fitted and supplied more than 40 individuals, ranging in age from 3 to 60, with prosthetic limbs, which range from $300 to $1,000 depending on if the device is being fitted for a child or for an adult and how many joints the prosthetic has.

“I feel like it gives them hope,” Kaliounji said.

One recipient was 4-year-old who got fitted with a new hand. There was the young man who lost a leg and who has since been able to return to his job as a baker. There was also the mother of six who lost both legs above the knee and whose inability to walk and work left her and her children in desperate need.

“Helping her meant I was helping an entire family,” said Kaliounji, whose dream is to expand Rise Again so she can provide sustained service in Syria and to become a doctor to help underserved communities around the world.

Maraashly, who works out of a small clinic that has also endured several bombings, said the need remains desperate.

“The war has been on for eight years now, with no electricity, no gas, no fuel,” he wrote in an email. “Medications and food are very expensive compared to income. It’s very hard to find work, people are displaced from their homes. Some children are able to go to school, others can’t.”

He said Haya’s work is imperative because there are many people in need who don’t have the means to pay for prosthetics or to replace them.

“We always try to find the poorest of people, especially those who show the will to go back to school and work after getting the device,” Maraashly wrote, noting that many people who have benefited from Rise Again have resumed their studies and employment.

Kaliounji has fond memories of growing up in Aleppo. She attended a local French school, took painting and drawing classes and piano lessons, was a dedicated Girl Scout and a member of the Syrian national under-14 tennis team. Then in 2011 violence erupted. She was 13.

By February 2012, Aleppo was under siege and enveloped in the violence. In the months that followed there were shootings and noise bombs, Kaliounji said.

“Our piano was next to the balcony window,” she recalled describing a day her lesson was interrupted. “Our house shook and we saw smoke in the horizon.”

When Kaliounji’s school closed, the family decided to move to neighboring Lebanon until it reopened. Her sister was already in Beirut for college and her brother was set to enroll at school there that fall.

“After three or four months we realized that the situation was getting worse and worse and that it was not a good idea to go back to Syria, especially for the safety of the kids,” said her mother, Fadia Kaliounji.

The family was able to move to Southern California, where some of their extended family had settled. They arrived in 2013.

“I feel like a lot of people got lucky to be able to leave, but there are so many people still there and they don’t have anything left,” Haya said. “This is why I do this work.”

Haya’s mother, who was a Girl Scout leader for 28 years in Syria, said that she wasn’t surprised by her youngest child’s ambitions because she has always been a kind-hearted person who thinks about and cares about others.

“I was so proud of her that she wanted to give back to her community in Syria,” mom said. “Especially for these young kids who have nothing to do with this war, but are affected.”

When the family enters UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion on June 14 to attend Haya’s graduation, they will take pride in knowing that she will be the second one to earn a UCLA degree. Haya’s brother, Aboud, graduated magna cum laude, with a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry in 2017 and is entering his second year of medical school in Grenada.

“I feel so proud of Haya and so proud for the family because we had the chance to have two children graduate from UCLA,” Fadia said. “Coming from Syria and from the war and have the opportunity to have two children graduate from UCLA, one of the best in the nation, is a big deal. I am so proud of them because they really worked hard.”

This article originally appeared on the UCLA Newsroom.