The stone faces and human problems on Easter Island

Excavation of Moai 156 (left) and 157. The visible difference in color and texture, and thus in preservation, is due to soil and depth coverage.

Archaeologist Jo Anne Van Tilburg continues to seek insight from the statues and for the living descendants of their makers

In 1981, UCLA archaeology graduate student Jo Anne Van Tilburg first set foot on the island of Rapa Nui, which is commonly called Easter Island, eager to explore her interest in rock art by studying the iconic stone heads that enigmatically survey the landscape.

Van Tilburg was one of just a few thousand people who would visit Rapa Nui each year back then. And though the island to this day remains one the most remote inhabited islands in the world, a surge in annual visitors has placed its delicate ecosystem and archaeological treasures in jeopardy.

“When I went to Easter Island for the first time in ’81, the number of people who visited per year was about 2,500,” said Van Tilburg, director of the Easter Island Statue Project, the longest collaborative artifact inventory ever conducted on the Polynesian island that belongs to Chile. “As of last year the number of tourists who arrived was 150,000 from around the world.”

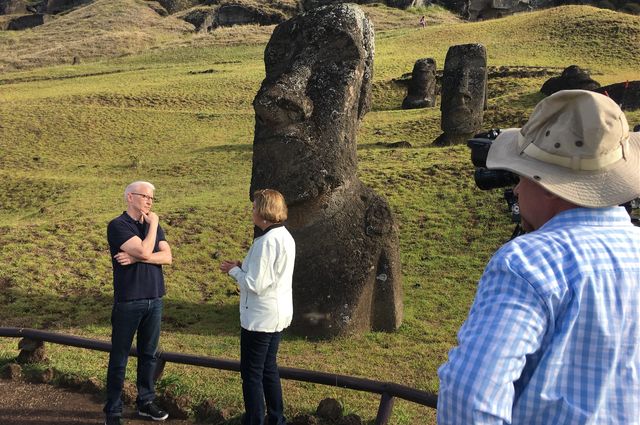

On April 21, which is Easter Sunday, CBS’ “60 Minutes” will air a special interview with Van Tilburg and Anderson Cooper filmed on the island, talking about efforts to preserve the moai (pronounced MO-eye) — the monolithic stone statues that were carved and placed on the island from around 1100 to 1400 and whose stoic faces have fascinated the world for decades.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg, right, and Cristián Arévalo Pakarati

Back in 2003, Van Tilburg, who is research associate at the UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology and director of UCLA’s Rock Art Archive since 1997, was the first archaeologist since the 1950s to obtain permission from Chile’s National Council of Monuments and the Rapa Nui National Park, with the Rapa Nui community and in collaboration with the National Center of Conservation and Restoration, Santiago de Chile, to excavate the moai, which most people didn’t know included torsos, which are buried below the surface, prior to her work and the publicity surrounding it.

Her success in obtaining permission to dig on the island, she credits to a philosophy of “community archaeology.” She has spent nearly four decades among the people of Rapa Nui, listening, learning, making connections, making covenants with the elders of the society, reporting extensively on her findings. Major funding has been provided by the Archaeological Institute of America Site Preservation Fund.

“I think my patience and diligence was rewarded,” she said. “They saw me all those years getting really dirty doing the work. What they don’t like is when people come and think they have all the answers and then leave. That feels to the Rapanui like their history is being co-opted.”

Van Tilburg credits the sustained and generous support of UCLA’s Cotsen Institute as critical to her continued work on the island. She has also made it a point to include UCLA undergraduates from a variety of academic disciplines in the hands-on work on Rapa Nui, including Alice Hom who began as a work study student 20 years ago and who now serves as project manager for the Easter Island Statue Project.

Van Tilburg, who received her doctorate in archaeology from UCLA in 1989, is working on a massive book project harnessing her vast archive that will serve as an academic atlas of the island, its history and the meaning behind the moai. She used the proceeds of a previous book to invest in a local business, the Mana Gallery and Mana Gallery press, both of which highlight indigenous artists. And she helped the local community rediscover their canoe-making history through the 1995 creation of the Rapa Nui Outrigger Club.

Jo Anne Van Tilburg being interviewed by Anderson Cooper of “60 Minutes”

Her co-director on the Easter Island Statue Project, Cristián Arévalo Pakarati, is Rapanui and a graphic artist by trade. Van Tilburg exclusively employs islanders for her excavation work. She’s traveled the world helping catalog items from the island that are now housed in museums like the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and the British Museum in London. Van Tilburg does this to assist repatriation efforts.

Rapa Nui is more commonly known as Easter Island because Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen first landed there on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1722. But the people who already lived there (Polynesian descendants of a massive human migration more than 500 years earlier), simply called the place “home,” Van Tilburg said.

“Very few pacific islands originally had names,” Van Tilburg said. “What was named was a landmark or a star or something that brought you to it, but not necessarily the island itself.”

The “60 Minutes” interview also focuses on how current residents of the island are coping with increasing waves of tourism, which is almost always a double-edged sword, but is especially so in a fragile ecosystem, Van Tilburg said.

The now 150,000 annual visitors pale in comparison to the vast numbers of travelers who flock to Egypt’s pyramids and awe-inspiring archaeological sites, she noted.

The intricate rock art on the back of Moai 157.

“But by Rapa Nui standards, on an island where electricity is provided by a generator, water is precious and depleted, and all the infrastructure is stressed, 150,000 is a mob,” she said.

What’s more disheartening is the frequent disrespectful nature of some travelers who ignore the rules and climb on the moai, trample preserved spaces and sit on top of graves all in service of getting a photo of themselves picking the nose of an ancient artifact, Van Tilburg said.

The masses and the increasingly harmful glibness of the travelers are something the 5,700 residents of the island must grapple with. Only in the last decade or so have they been given governance of the national park where the moai are located. In 1995, UNESCO named Easter Island a World Heritage Site, with much of the island protected within Rapa Nui National Park.

Van Tilburg’s original impetus behind studying the moai is rooted in her curiosity about migration, marginalized people and how societies rise and fall.

“Rapa Nui was the last island settled probably in the whole westward movement that took place from southeast Asia across the Pacific,” Van Tilburg said. “I’m interested in what that might signal to us about today and why people are moving around the world the way they are.”

Rapanui society was traditionally hierarchical, led by a class of people who believed themselves God-appointed elites. These leaders dictated where the lower classes could live, how they would work to provide food for the elites and the population at large. The ruling class also determined how and when the moai would be built as the backdrop for exchange and ceremony.

“This inherently institutionalized religious hierarchy produced an inequitable society,” Van Tilburg said. “They were very successful in the sense that their population grew and they were good horticulturists, agriculturists and fisherman. But they were unsuccessful at understanding that unless they managed what they had better, and more fairly, that there was no future.”

Population growth and rampant inequity in a fragile environment eventually led to wrenching societal changes, she said. Internal collapse (as outlined in UCLA professor Jared Diamond’s book “Collapse”) along with colonization and slave-trading in the 1800s caused the population of Rapa Nui to drop to just 111 in the 1870s.

As an anthropologist, Van Tilburg is deeply interested in equity.

“I’m interested in asking why do we keep replicating societies in which people are not equal, because in doing so, we initiate a crisis,” she said. “Inequity is at the heart of our human problems.”

This story originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.