UCLA researchers determine the structure of a toxin that kills malaria-carrying mosquitoes

Results pave the way for genetically engineering the toxin to be lethal to other mosquito species transmitting Zika virus and dengue fever

By Katherine Kornei

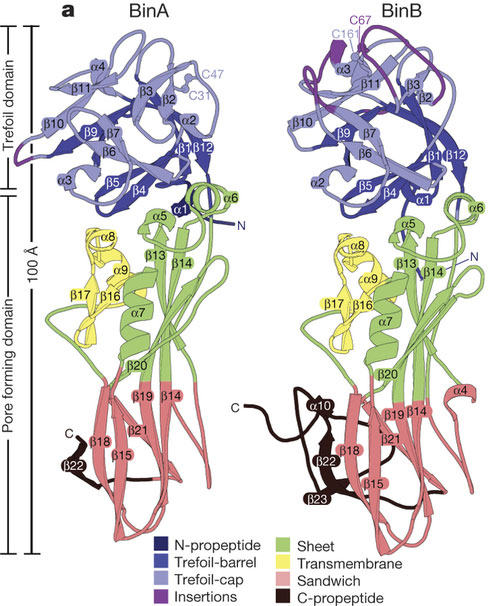

Figure showing BinA and BinB folds and carbohydrate-binding modules. BinA and BinB are structurally similar to each other. The most noticeable differences correspond to insertions in surface loops on the trefoil domains (purple). UCLA researchers used an X-ray laser to determine the arrangement of atoms.

An international team of scientists, including five UCLA researchers, has used X-rays to reveal the structure of a molecule toxic to disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk of contracting malaria, a life-threatening disease transmitted by mosquitoes. Chemical insecticides are often a first line of defense against mosquitoes, but their application can result in both environmental pollution and resistance to the pesticide. The research was published in the journal Nature.

Countries around the globe have recently begun killing mosquito larvae using a natural toxin derived from bacteria. Now UCLA scientists and their collaborators have used X-rays to determine the atomic structure of this larvicide, which is lethal to mosquitoes transmitting malaria and West Nile virus. These results reveal how the toxin functions, knowledge that will inform future efforts to genetically engineer it to also kill mosquitoes carrying Zika virus and dengue fever.

“This is a chance to have a positive effect on a lot of the world’s population,” said senior author David Eisenberg, UCLA’s Paul D. Boyer Professor of Molecular Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Eisenberg and his colleagues studied the larvicide known as BinAB, which is produced by soil-dwelling bacteria. The bacteria pack BinAB into tiny crystals, thousands of which could be stacked across the head of a pin. When these crystals are scattered into the watery environments in which mosquitoes thrive, hungry mosquito larvae eat the crystals. But the meal turns out to be a deadly one.

As the crystals pass through the larvae’s digestive tract, the gut juices of the larvae trigger the crystals to dissolve. The BinAB toxin is released, and its component molecules — called BinA and BinB — play distinct roles in entering the cells of the larvae’s guts and killing the young mosquitoes within 48 hours.

BinAB is toxic to the Culex and Anopheles species of mosquitoes — carriers of West Nile virus and malaria, respectively — but at this point is harmless to the Aedes species, the carriers of Zika virus and dengue fever.

“The toxin is this complex shape, and it has to fit with another shape on the intestine of the larvae. If the shapes don’t match up precisely, the toxin cannot get in the cell. It’s like a lock and key,” said Michael Sawaya, a staff scientist at UCLA involved in the study, to explain BinAB’s specificity.

Genetically engineering an effective toxin

Researchers are interested in genetically engineering BinAB to also kill the larvae of Aedes mosquitoes, work that requires a detailed understanding of BinAB’s atomic structure. However, the small size of the crystals containing BinAB has made it difficult for scientists to hold them securely in laboratory instruments for analysis.

The UCLA researchers and their colleagues, including Dr. Jacques-Philippe Colletier, a former UCLA researcher now working in France, overcame this size limitation by harvesting crystals from a particular strain of soil-dwelling bacteria engineered to produce larger crystals. The scientists then studied the precise shape of the BinAB toxin within the crystals using an X-ray laser. Eisenberg and his colleagues bombarded the crystals with an X-ray laser invented by a UCLA physicist.

“When we shine X-rays on the crystals, the X-rays are scattered into thousands of X-ray beams,” said Eisenberg, who is also a professor of chemistry, biochemistry and biological chemistry and a member of UCLA’s California NanoSystems Institute. “These beams contain information about the arrangement of the atoms that make up BinA and BinB.”

“It would be hard to find a problem that could potentially affect the health of more people.” – Senior author David Eisenberg

Novel use of X-ray laser

This type of X-ray laser has never before been used to study a sample with an unknown structure. “We can do entirely new types of experiments using these X-ray lasers,” said co-author Jose Rodriguez, a UCLA assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry.

The researchers found that the BinA and BinB molecules making up BinAB were crossed in an “X” shape. “They’re hugging each other,” Eisenberg said of the BinA and BinB molecules. This geometry helps ensure that the BinA and BinB molecules exist in equal numbers, which contributes to BinAB’s toxicity.

The scientists also isolated four special sites on the BinAB toxin that were most likely to be involved in the larvicide splitting into BinA and BinB, a transformation critical to the lethal nature of the toxin.

“You can think of the molecule as…having four latches,” Rodriguez said. “When these latches open, the molecule can change its shape. These crystals have to go through a lot of transformations before they actually reach the target location.”

The scientific world is now one step closer to genetically engineering BinAB to be lethal to the mosquitoes that carry Zika virus and dengue fever.

Eisenberg is optimistic. “It would be hard to find a problem that could potentially affect the health of more people,” he said.

Funding sources for the research include the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, W.M. Keck Foundation, National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science and Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

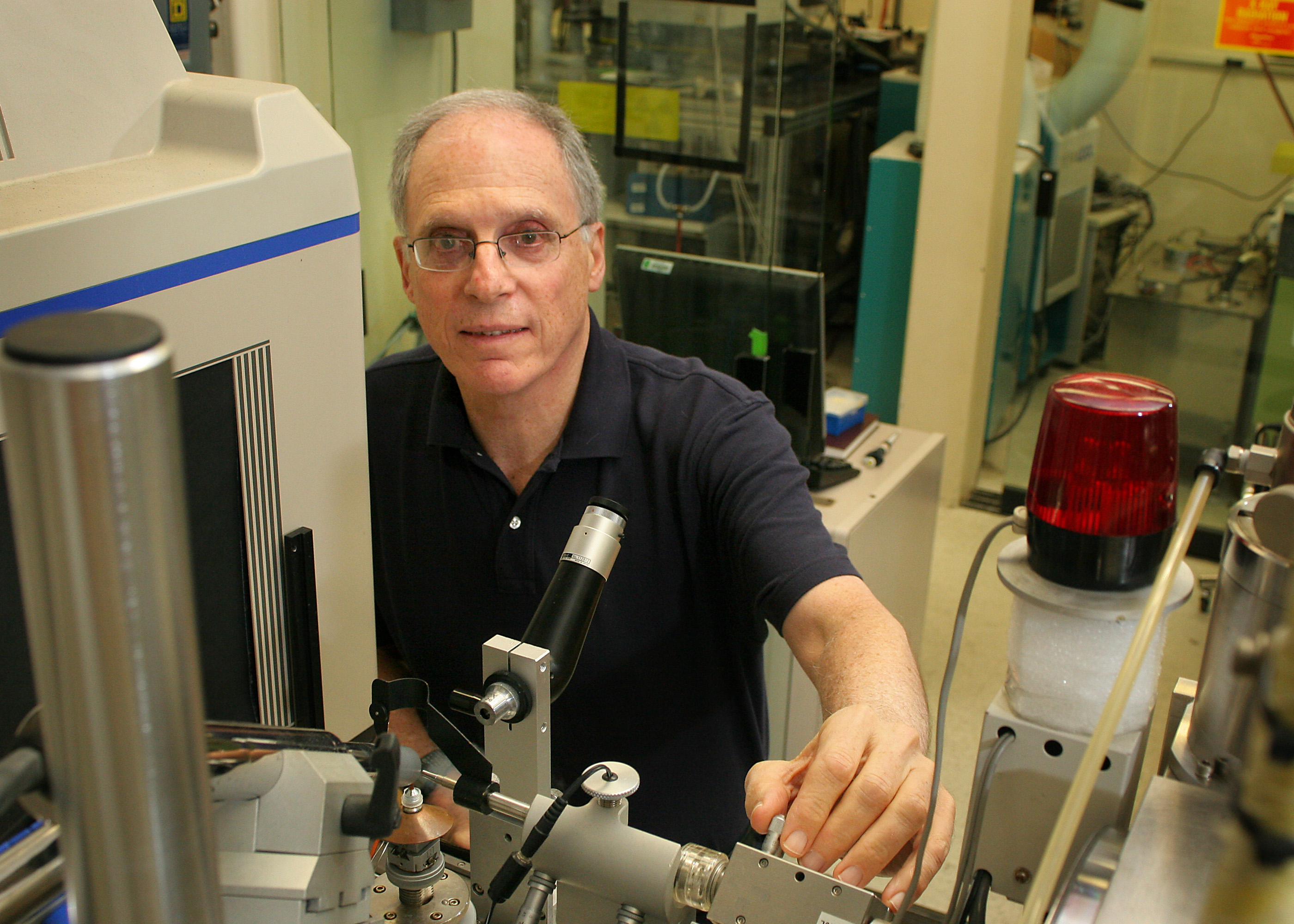

David Eisenberg, UCLA’s Paul D. Boyer Professor of Molecular Biology

Meet the Professor- In his own words

Meet the Professor- In his own words