Mapping the costs of incarceration in Los Angeles

Million dollar hoods website provides unprecedented access to jail data

By Jessica Wolf

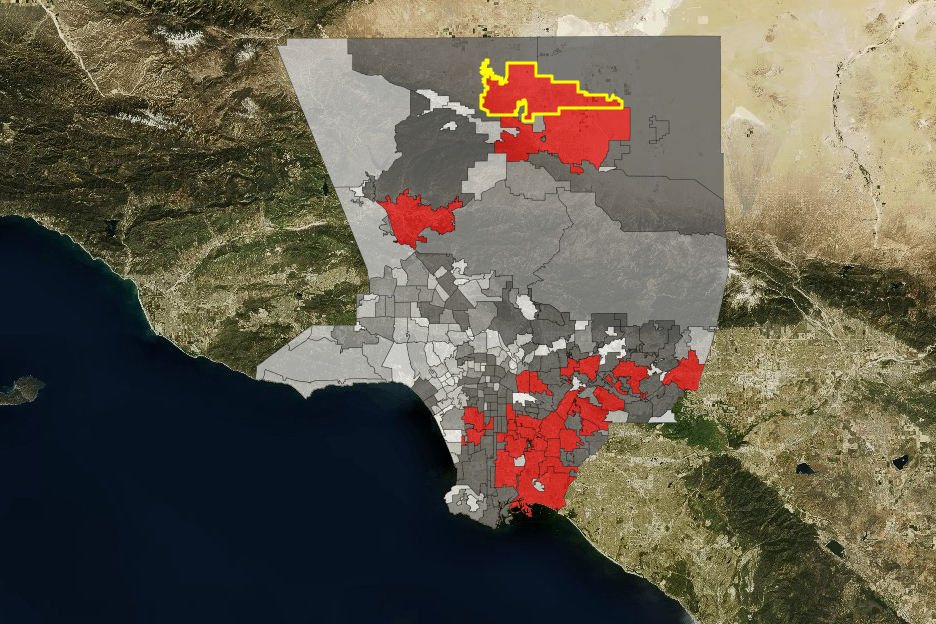

Image: The Million Dollar Hoods website lets users examine incarceration data for dozens of areas in Los Angeles County. In this screen grab from the site, the red sections of Los Angeles County show where the most money is spent locking up people from that area.

As the realities of mass incarceration face increased scrutiny across the nation, UCLA researchers have launched Million Dollar Hoods, a website and digital mapping project that shows the disparate impact of the Los Angeles jail system — the largest in the United States.

Million Dollar Hoods maps how much money the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and the Los Angeles Police Department spend per neighborhood to incarcerate residents in county and city jails.

The project’s goal is to provide unprecedented public access to jail data in Los Angeles and identify patterns of incarceration throughout the county. The maps also let users examine the data by race, gender, type of crime and leading cause of arrest for every neighborhood.

“What we have uncovered is that L.A.’s nearly billion-dollar jail budget is largely committed to incarcerating residents of just a few neighborhoods,” said Kelly Lytle-Hernandez, UCLA professor of history and African American Studies. “In some neighborhoods, such as Lancaster, Palmdale and Compton, tens of millions of dollars have been spent since 2010.”

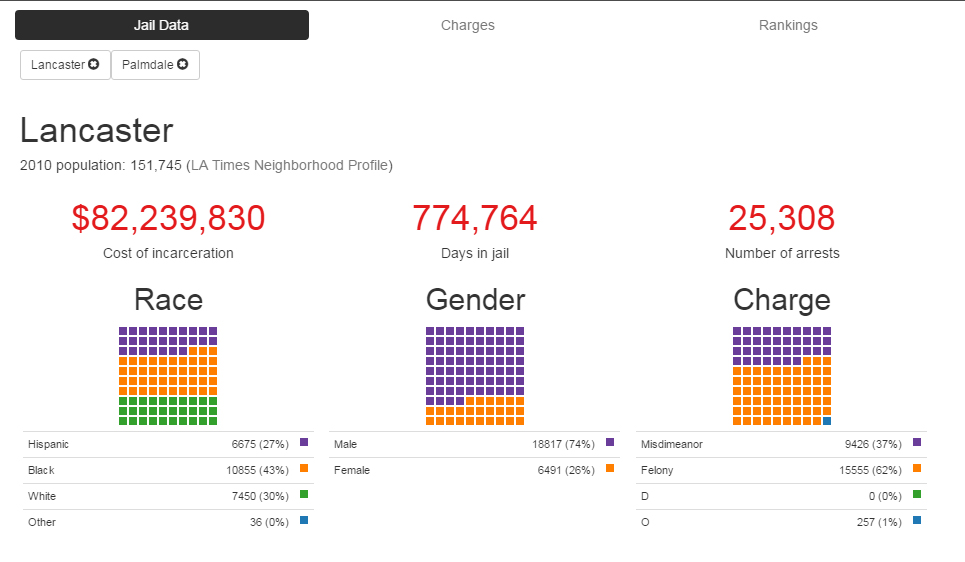

Breaking down a billion-dollar jail budget

Since 2010 Los Angeles County spent more than $82 million incarcerating residents from Lancaster and more than $61 million incarcerating people from Palmdale, with DUI and possession of a controlled substance the top two causes of arrest. In that time, nearly $40 million was spent incarcerating residents from Compton, where the top cause of arrest was possession of a controlled substance.

Lytle-Hernandez, who led the project, secured the required data via requests to the sheriff’s department and LAPD through the California Public Records Act. The sheriff’s department repeatedly denied her requests but granted access in January 2016. Since then, she has worked with a team of UCLA geographic information systems experts to bring to Los Angeles a robust mapping database that has been successfully used in New York, Chicago, New Orleans and elsewhere.

“Much like the Million Dollar Blocks projects in New York and Chicago, we are looking at the costs of incarceration by identifying the communities where the most has been spent to incarcerate residents,” Lytle-Hernandez said. Million Dollar Hoods differs from those projects in that it uses local jail data versus state prison data.

Image: Los Angeles County Men’s Central Jail in downtown. Los Angeles operates the largest jail system in the United States. PHOTO: Mike Fricano/UCLA

“We made this choice because Los Angeles operates the largest jail system in the United States and we wanted to betterunderstand the impact of L.A.’s jails and lockups,” Lytle-Hernandez said.

Lytle-Hernandez pointed out that the dollar amounts posted on the Million Dollar Hoods map are conservative estimates owing to gaps in how the departments track this information. For example, the sheriff’s department does not record the number of days spent incarcerated by people who may have posted bail but then returned to custody after trial. The data also do not capture information on prisoners transferred into the L.A. County jail system from city police departments or the California state prison system.

For many of the communities mapped in this project, the total cost of incarceration to the L.A. County jail system is actually much higher, Lytle-Hernandez said.

Connecting data to personal stories

“But the costs of incarceration are more than fiscal,” Lytle-Hernandez added. “So we are committed to also sharing the personal experiences that residents of L.A.’s Million Dollar Hoods have had with arrest and incarceration, allowing for a fuller accounting of the social costs of incarceration, to families, communities and society at large.”

The Million Dollar Hoods research team has partnered with the Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations, which is currently holding a series of public hearings on policing in Los Angeles. At these hearings, the commission is inviting community members to share their experiences with law enforcement officers and agencies. The Million Dollar Hoods website hosts video footage of testimony from these hearings.

Geographic information systems technologists Yoh Kawano and Albert Kochaphum from UCLA’s Institute for Digital Research and Education coded and mapped the data and built the website. Robert Habans, a fellow at the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, identified data trends and developed the formulas that revealed the rate of daily incarceration costs per prison bed.

Image: Incarceration data for Lancaster, California. PHOTO: milliondollarhoods.org

Collaborating with law enforcement, advocacy groups and media

The team plans to work with LAPD and the sheriff’s department to regularly add information to the maps. Million Dollar Hoods research partners also include several community-based organizations that are working to reform systems of incarceration in Los Angeles. Representatives from Critical Resistance-Los Angeles, Californians United for a Responsible Budget, Dignity and Power Now, and Youth Justice Coalition are collaborators in the Million Dollar Hoods project.

Million Dollar Hoods also has partnered with Los Angeles public radio station KCRW for a six-episode series that launched Sept. 13. Off the Block will examine how a trip to jail, even for just a few hours or days, can upend many lives, tracing the path from city block to jail block and back.

Lytle-Hernandez will also release her new book City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles this spring. It is a history of incarceration in the city from the days of Spanish conquest to the outbreak of the 1965 Watts Rebellion.

In City of Inmates she marshals two centuries of evidence to show that incarceration has historically and consistently operated to remove, banish, and otherwise eliminate unwanted communities from the city. Across time, some of the communities most targeted for incarceration have been indigenous peoples, sexual minorities, non-white immigrants and African Americans.

UCLA’s Million Dollar Hoods project is supported by the John Randolph and Dora Haynes Foundation, the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, and the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

LEARN MORE:

Visit Million Dollar Hoods at http://milliondollarhoods.org

Listen to episodes of KCRW’s Off the Block at http://kcrw.co/2ejmN5t

Meet the Professor- In his own words

Meet the Professor- In his own words