Q&A: Bridging theory and practice in linguistics

UCLA double alumnus and donor Tom Bye on his linguistics journey and commitment to education

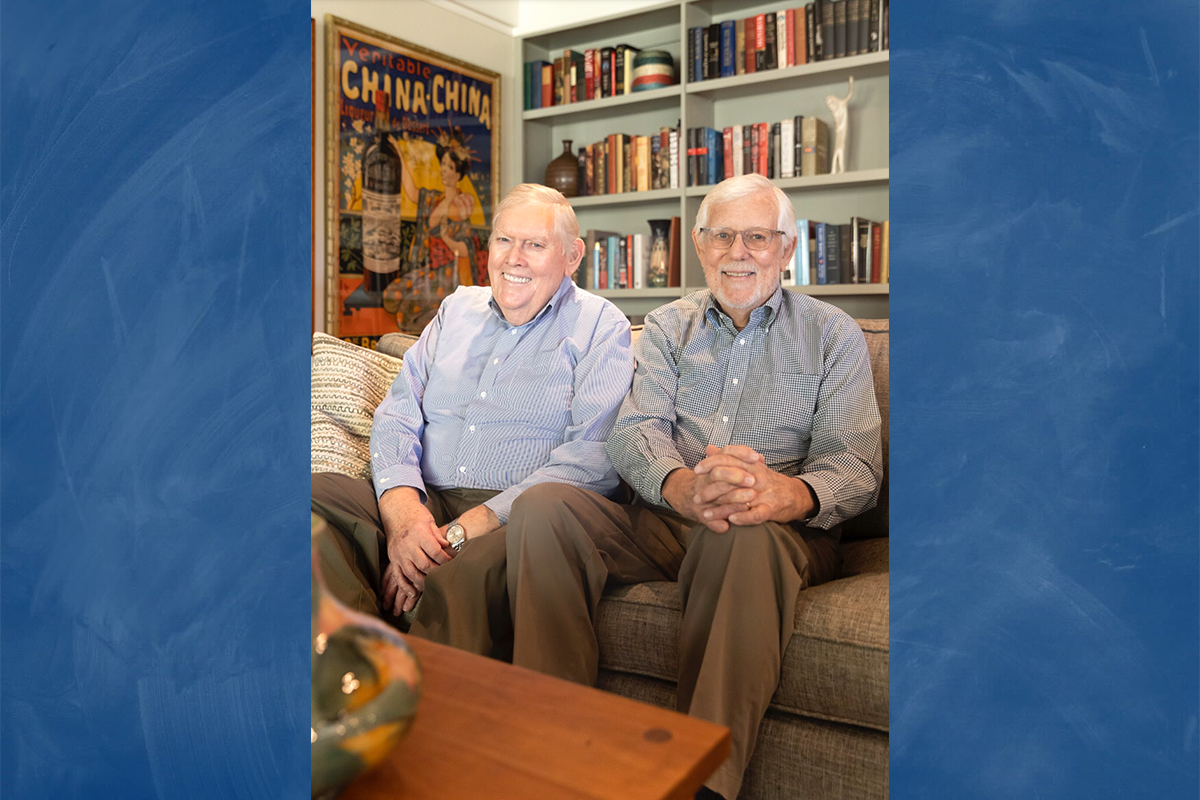

Husbands David Bohne and Tom Bye

Brittany Hosea-Small

By UCLA College | December 3, 2024

For anyone interested in a career in linguistics, Tom Bye’s initial advice might seem simple: “Be ready to work hard. Attempt to have fun.” But the graduate of UCLA’s linguistics master’s and Ph.D. programs — and his husband David Bohne — agree that this balance can be a challenge to achieve. Doing so, however, has afforded them the ability to give back while moving the field forward. But what inspired Bye to begin his linguistics journey in the first place, and what does he hope his impact will make possible for it?

We spoke with Bye to hear more.

What first sparked your interest in studying linguistics?

Because I had been a foreign language major, I had thought linguistics might be a great next step. I did my homework and discovered that the linguistics department at UCLA enjoyed — and still enjoys — a stellar reputation. This was a daring move since I had no undergraduate coursework in linguistics. I remember that I was very worried about getting admitted. On my application letter, I indicated that I was interested in machine learning — not really true but prescient (!) — and happily, I was accepted.

What are some memorable moments from your UCLA grad school experience in the field?

I loved the friends I made and enjoyed interacting with my professors, many of whom treated graduate students as colleagues. Most of all, I loved working hard and experiencing success in a challenging field in which I had very little preparation. Fortunately, I had the love and support of my future husband, who not only had a job that made this possible but even mowed the lawn as I wrote my dissertation.

How would you describe your particular research focus to a layperson?

I would tell my story: I was blessed to have Sandra Thompson as my chair! Sandy was interested in discourse and I had an interest in children’s acquisition of communicative competence. I first spent three or four months at a Montessori school — watching, listening and involving myself in children’s work and play activities. I determined at some point that I would examine how children produce locative directions — getting from one place to another.

Here’s how it worked: I designed a simulation — a game — involving an imagined house fire and a phone call to the firehouse to report the fire. I built a village to scale that included houses and a fire station. For the game, I donned a firefighter’s hat and covered my eyes with a mask. I provided both the child (whose house was on fire) and myself (the firefighter) with a telephone. I asked the child to call me and give directions for getting to the burning house. Children aged three to ten were involved in the task, and the language was, of course, recorded and examined.

What I learned: My research confirmed the developmental nature of discourse competence as well as the link between language and cognition. Crucially, as children grow older, they show an increased awareness of the listener — taking into account what the listener knows and doesn’t know — and they use language that reflects this understanding. We see greater saliency. Sentences become increasingly well formed and syntactically complex.

You spent five years in graduate school in a very theoretical field — but didn’t follow an academic career path. You needed to get a job. What did you do?

Sandy put me in touch with several colleagues of hers who were involved in the National Origin Desegregation Assistance Center for Northern California — an agency charged with delivering technical assistance to school districts found out of compliance with the Civil Right Act of 1964 because of failure to provide special services to English learners. I was the “linguist” on the team, helping schools design effective instructional programs and utilize best teaching practices in ESL and bilingual education. From there, I moved to a Bay Area school district, where I served in various district-level administrative positions for nearly 20 years. And, for the final years of my career, I provided consultant services to school districts in program planning, development and evaluation — always focusing on English learners. I also authored ESL programs for both Prentice Hall and for McGraw Hill Education, utilized by schools in the U.S. and the Middle East.

The lesson: there is a life after grad school!

Why is applied linguistics so important and impactful?

Linguistics potentially offers answers to questions that educators, journalists, policymakers, the courts and the public might have about language use in a variety of settings and for a range of purposes.

What is your ultimate hope for the impact of your chair?

I’m hopeful that every holder of the chair will be seen as an effective advocate for bridging theory and practice. I also hope that future graduate students will see how linguistics can provide pathways to careers in both academia and the outside world of work.