Q&A: David Paige on the Mars Perseverance landing

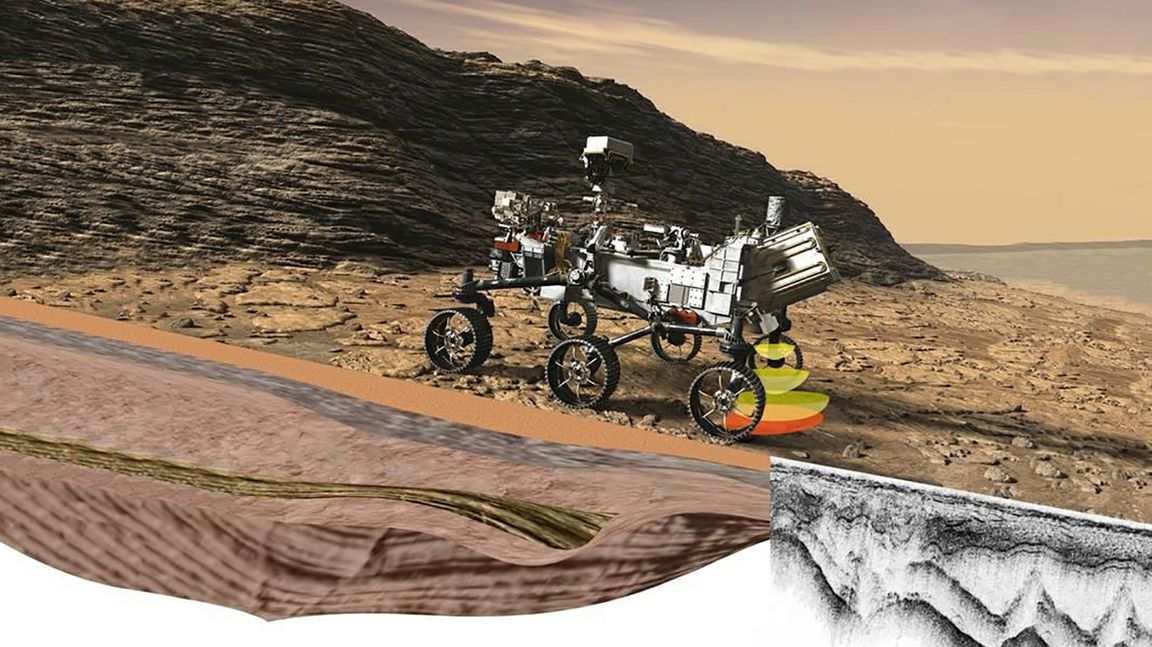

Rendering of the NASA Perseverance. The rover’s RIMFAX technology will use radar waves to probe the unexplored world that lies beneath the Martian surface. (Photo Credit: NASA/JPL/Caltech/FFI)

NASA’s Perseverance rover is scheduled to land on Mars on Feb. 18 after a six-and-a-half month flight. Over the next two years, it will explore Jezero Crater, which is in Mars’ northern hemisphere, for signs of ancient life and for new clues about the planet’s climate and geology.

Among other tasks, it will collect rock and soil samples in tubes that a later spacecraft will bring back to Earth, and the experiments will lay the groundwork for future human and robotic exploration of Mars.

Perseverance, which is about the size of a car, is outfitted with seven different instruments, including the Radar Imager for Mars‘ Subsurface Experiment, or RIMFAX. RIMFAX will probe beneath the planet’s surface to study its geology in detail, and its deputy principal investigator is David Paige, a UCLA professor of planetary science.

In an email interview with UCLA Newsroom, Paige discussed his hopes for the mission. Some answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Why do you want to study Jezero Crater’s geologic history?

Jezero Crater is a very interesting location on Mars because it looks like there was once a lake inside the crater, and that a river flowed into the lake and deposited sediments in a delta. We plan to land near the delta and then explore it to learn more about Mars’ climate history, and maybe something about ancient Martian life. What we’ll be able to see once we start roving and what we will actually learn is anybody’s guess.

RIMFAX will provide a highly detailed view of subsurface structures and help find clues to past environments on Mars, including those that may have provided the conditions necessary for supporting life.

David Paige (Courtesy of David Paige)

What are you hoping to discover?

Well, the first thing to know about RIMFAX is that it’s an experiment. We’ve never tried using a ground-penetrating radar on Mars before, so we can’t really predict what types of subsurface structures we might be able to see.

But we have done some fairly extensive field testing of RIMFAX on Earth to learn how to use it and how to interpret the data. Here, ground-penetrating radars can be very useful for clarifying subsurface geology, but with any kind of imaging system, the science of ground-penetrating radar comes from the interpretation of the images, and interpretation relies on context.

Frankly, if we are able to usefully interpret anything we see in the RIMFAX data, the experiment will be a success. Any discoveries we make beyond that will be icing on the cake.

Are you hopeful of finding water, or evidence of water, beneath the planet’s surface?

There are all kinds of evidence for past liquid water all over Mars. At Jezero, there must have been a lot of water at some point, but we don’t expect that the ground beneath the rover will still be wet.

Mars today is a very cold place, and any water in the shallow subsurface should be frozen at Jezero. What we’re interested in finding are geologic features that wouldn’t be expected to form under present climatic conditions, as those would be especially interesting targets to search for signs of past life.

However, searching for past life on Mars may be very difficult, and we should not expect instant success. After all, we know the Earth was literally crawling with life, but definitive evidence for past life on Earth, especially ancient life, is very rare.

What is your role in the research?

My role is to help plan the observations and analyze the results. Since the rover will be working on Mars time, in which the days are 24.5 hours long, responsibility for the operation of RIMFAX will pingpong between Norway and UCLA every two weeks. Having operations centers on two continents will make it easier to keep up with the mission and stay on a reasonably normal schedule.

In fact, RIMFAX was designed, paid for and built by our colleagues in Norway. I teamed up with my colleague, Svein-Erik Hamran of the University of Oslo, to propose the instrument to NASA, and it has been a rewarding experience to work with the international RIMFAX team.

Are UCLA students involved?

Yes. Mark Nasielski, a UCLA graduate student in electrical engineering, is part of our operations team. And Max Parks and Tyler Powell, graduate students in Earth, planetary and space sciences, are part of our science team.

This article, written by Stuart Wolpert, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.