California has removed most obstacles to voting. Why are so many still not going to the polls?

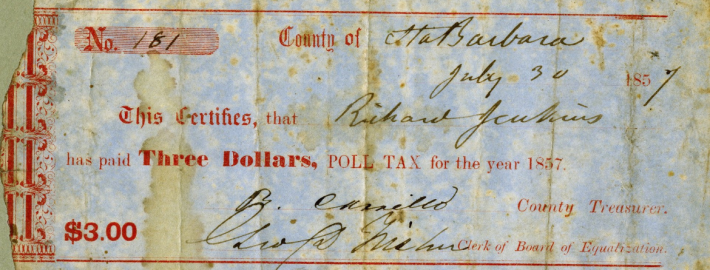

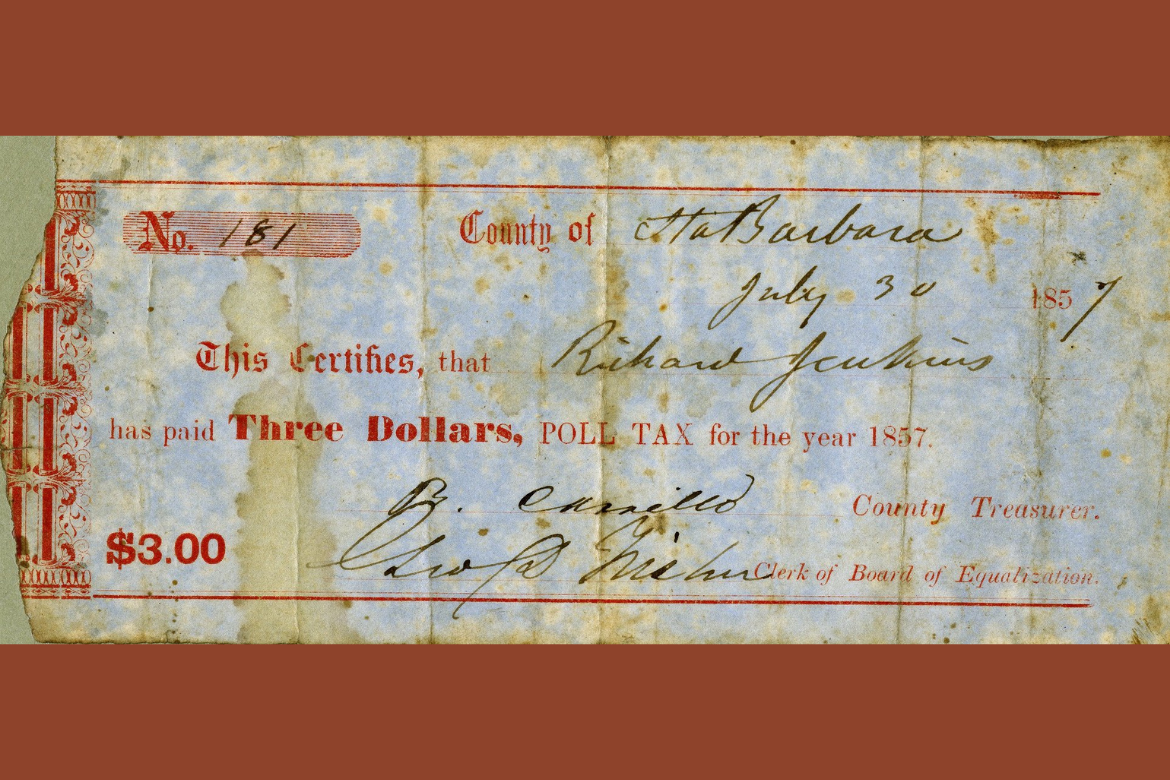

During California’s early years, paying a poll tax was considered an obligation of citizenship. (Photo Credit: Edson Smith Photo Collection/Courtesy of the Santa Barbara Public Library)

A new report by the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy takes a historical view to understand why, in 2020, the electorate in California remains demographically and socioeconomically skewed.

The authors contend that vote-by-mail, near-automatic voter registration, a vote-by-mail ballot tracing system and other practices have expanded voting rights to most Californians. Yet longstanding inequities in voting patterns persist.

Despite persistent statewide policy efforts to increase voting access since 1960, voter registration and turnout are lower among people of color than among white people, the report notes. And California voters today — especially those who vote by mail — tend to be older, wealthier and whiter than the state’s overall population. For example, in Los Angeles County, wealthier and whiter districts cast as many as 40% more votes than those with heavily Latino and working-class populations.

The paper suggests that ongoing factors like gerrymandering and the disenfranchisement of former felons who are on parole may explain part of that phenomenon. (If it passes in November, however, California’s Proposition 17 would enable people on parole for felony convictions to vote.)

“Notwithstanding the efforts of the past 60 years, California still has work to do,” said Alisa Belinkoff Katz, the report’s lead author and a fellow at the center, which is housed in the UCLA College. “California’s electorate does not reflect the diversity of its population. We can only meet the present moment if we understand and eliminate policies that have historically restricted the franchise.”

For the first hundred years after 1850, when California became a state, voting laws limited access to the franchise, in effect suppressing the vote of poor and minority populations. The state passed several such policies during the late 1800s, including English literacy tests. And the federal government banned citizenship for most Native Americans and all Chinese immigrants, excluding them from the franchise altogether.

California also implemented stringent voter registration rules that made voting more difficult for people with lower incomes and those without a settled address.

After World War II, however, state officials changed course. They worked diligently both to overturn discriminatory policies and to make it easier to register and vote, launching voter registration drives, expanding absentee voting, and experimenting with all-mail elections. The state has passed legislation designed to expand the franchise almost every year since 1960.

But the study reinforces the reality that structural inequality still keeps many Californians from participating in the political process.

“California, and American society at large, must reckon with and overturn the racial and socioeconomic barriers that discourage or prevent large numbers of eligible voters form voting,” said David Myers, a UCLA professor of history and director of the Luskin Center.

Other key takeaways from the report:

– California enacted voter registration — requiring a settled address — in 1866. This limited access to the vote for the working class, poor, immigrants and racial minorities.

-From the 1890s to 1924, voter turnout in presidential elections dropped dramatically across the United States, from around 80% of eligible voters to just 49%, in part because of voter registration laws.

-California suppressed the vote with an 1899 law requiring voters to re-register every two years. The state established permanent voter registration in 1930, but that law also purged thousands of registered voters from the rolls each year if they had failed to vote in prior elections.

-A constitutional amendment allowing absentee voting barely passed in 1922 after failing three previous times. But the use of absentee voting was limited until a series of reforms beginning in 1978. Today, the vote-by-mail option is open to all, but it has not been used by all Californians at equal rates.

-An English literacy requirement for voting remained on the books until the early 1970s. It was rarely applied to European or Asian immigrants, but in the 1950s it was sometimes used by political candidates to challenge Mexican American voters at the polls.

Katz is also associate director of the Los Angeles Initiative at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. The research team also included Zev Yaroslavsky, a senior fellow at the center; Izul de la Vega, a UCLA doctoral student; Saman Haddad, a UCLA undergraduate; and Jeanne Ramin, a recent UCLA graduate. As part of their research, the authors interviewed California Secretary of State Alex Padilla and Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk Dean Logan, two of the state’s most important elections officials.

This article, written by Maia Ferdman, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.