Voices from UCLA Humanities share how the division’s academic rigor and creativity offer a global lens

By Kayla McCormack and Jonathan Riggs | Art by Katie Sipek

December 12, 2024

More than just a guiding principle, “Word to World,” the motto of the UCLA Division of Humanities, conveys how all disciplines in this area connect us to one another across geographic space and chronological time. In countless ways, the humanities open up vibrant avenues of travel, study, collaboration and creativity around the globe. Here are five prisms through which to view them.

Explore more by clicking on the puzzle pieces below.

WE ARE ALL INTERCONNECTED

The recent $31 million gift from Japanese executive Tadashi Yanai — the largest-ever gift to the UCLA Division of Humanities — will further advance the existing Yanai Initiative for Globalizing Japanese Humanities while supporting the Japan Past & Present initiative, an international resource.

According to UCLA Interim Chancellor Darnell Hunt, “Thanks to Mr. Yanai’s generosity, UCLA will continue to grow as a nexus for scholars across the world to come together to explore and exchange ideas, transcending political, linguistic and cultural boundaries.”

Similarly, thanks to an $11 million gift from the Persian Heritage Foundation, the university was able to establish the UCLA Yarshater Center for the Study of Iranian Literary Traditions last year, which is housed in the newly renamed UCLA Pourdavoud Institute for the Study of the Iranian World.

“In broad brushstrokes the Yarshater Center aims at preserving and introducing to the broader public the literary traditions of ancient and medieval Iran, by dint of an ambitious publication agenda,” said M. Rahim Shayegan, director of the center and institute as well as UCLA’s Jahangir and Eleanor Amuzegar Chair of Iranian Studies, at the launch event this past October. “All these endeavors are envisioned as collaborative works, authored by scholars throughout the world. We are committed that they be disseminated gratis in digital format, allowing scholars and global audiences to partake in their intellectual rewards.”

Another important effort in the division involves John Papadopoulos, distinguished professor of classics and professor of archaeology at UCLA, who also serves as director of excavations for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In that role, he is leading the excavation of the Athenian Agora, which is providing invaluable insights into the birth of democracy, arts and culture. This past summer, Dean of Humanities Alexandra Minna Stern and Dean of Social Sciences Abel Valenzuela visited the site as part of their respective divisions’ continued synergy.

“We are so impressed with the interdisciplinarity of this project and what it can teach us about ourselves and our work,” said Stern. “You can’t fully explore the past without the crucial tools inherent to both humanities and social sciences, nor can you fully navigate the future.”

STUDY ABROAD

For humanities students, the world outside the classroom holds the richest lessons. Whether strolling through Madrid’s historic parks, savoring the flavors of Seoul or standing before timeless works of art in Copenhagen, the immersive experience of studying abroad offers transformative learning moments. For a select group of UCLA students, this experience is made possible by the Komar Shideler Study Abroad Scholarship, which funds such opportunities for undergraduates in the humanities.

Beyond academic learning, scholars who study abroad increase their cross-cultural understanding, develop language skills and build personal resilience as they adapt to life far from home.

For David Montoya, a history and Spanish major, the experience was life-changing. His time exploring cities throughout Spain allowed him to engage with various cultures, traditions and languages. He met new people, navigated cities and expanded his culinary horizons by trying local specialties.

“Traveling broadens your perspective of the world and how interconnected history, culture and language are,” Montoya said. “This experience deepened my academic knowledge and inspired me to continue exploring and learning from different cultures.”

In 2016, professors Ross Shideler and Kathleen Komar recognized the importance of making these experiences accessible to more students. They established a scholarship in their names to support humanities students studying abroad, particularly undergraduates who are pursuing studies in comparative literature and Scandinavian languages or who participate in programs in Scandinavia. The scholarship supported a first cohort in 2019; since then, 13 students have benefited from it.

“We give to support the study of languages and literature at UCLA because we need to understand other cultures and traditions now more than ever,” Shideler and Komar said.

Ensuring Bruins from all backgrounds can participate thanks to scholarships that ease their financial burden inspired these donors and others like them.

“Scholarships such as the Komar Shideler are critical to fostering interest in the humanities at UCLA,” said Magdalena Barragán, executive director of UCLA’s International Education Office. “The number of students who major in humanities has decreased overall at UCLA over the past decade, so funding like this encourages students and creates opportunities for exploration and experiential learning.

“For several years, for example, the scholarship has made the ELTS travel study program ‘In the Footsteps of Hans Christian Andersen’ a reality for students who could not otherwise afford to participate,” she added. “Through this program, students learn about the fairy tales and work of the renowned Danish author in an immersive manner that furthers their learning and understanding of the author.

“Incomparable experiences supported by scholarships are essential to create globally minded and intellectually curious Bruins,” Barragán concluded. “These unique learning opportunities are kept viable and available to all through this type of financial support.”

Claudia Chen, who graduated in 2024 with majors in comparative literature and Asian languages and linguistics, was able to study abroad in Seoul, South Korea as a recipient of the Komar Shideler scholarship.

“Because of this scholarship, I was able to worry less about the financial costs of this study abroad experience, whether tuition-wise or the extra costs like flight, food, et cetera,” said Chen. “This also helped me maximize my experience in Korea by allowing me to explore more places, cultural events and more, without having to worry as much about how to afford it.”

Komar Shideler alumna Kendall Vanderwouw said her time studying in Copenhagen gave her the confidence to live abroad. She graduated from UCLA in 2024 and is currently living in Sweden, where she is pursuing a master’s in applied cultural analysis in a joint program at Lund University and the University of Copenhagen.

“It feels so difficult to push yourself to go out into the world,” said Vanderwouw. “But once you do it, you realize what you’re capable of and you can figure it out. You really grow the most as a person when you put yourself in uncomfortable situations.”

Meet four of the Komar Shideler Scholarship recipients:

Kendall Vanderwouw ’24

Kendall Vanderwouw ’24

Copenhagen, Denmark

Vanderwouw graduated with degrees in anthropology and linguistics and a minor in Scandinavian studies. During her time abroad, she studied mutual intelligibility in Scandinavian languages — that is, how linguistic similarity affects how people who speak Scandinavian languages understand each other.

“I speak Swedish, so I wanted to experience firsthand how that understanding comes about,” she said. “Trying to speak to people in Denmark using Swedish was a very interesting experience, and I think it gave me a much deeper understanding than I would have gotten anywhere else.”

Claudia Chen ’24

Seoul, South Korea

Chen graduated with degrees in comparative literature and Asian languages and linguistics. During her time in Seoul, Chen studied English under the context of Korean culture.

“It was quite the eye-opening experience to hear about well-known English texts through the perspective of native Korean students, who had a different outlook on society and morals than I was used to,” Chen said. “It really opened my mind up to considerations outside my own upbringing and American bubble, and I not only learned much about the texts I read in an academic sense, but I was also able to develop a deeper social understanding of literature in general.”

David Montoya ’23

Granada, Barcelona and Madrid, Spain

Montoya graduated in 2023 with degrees in history and Spanish. During his time in Spain, Montoya was able to immerse himself in Spanish language, culture and history.

“Exploring historic sites like the Alhambra in Granada and the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona gave me a deeper understanding of and appreciation for Spanish culture,” he said. “Additionally, interacting with Spaniards and communicating in the language broadened my communication skills and allowed me to make the cultural and historical elements more meaningful.”

Gabrielle Lopez ’27

Copenhagen, Denmark

Lopez is set to graduate in 2027 with a degree in world arts and cultures. Studying abroad gave her the opportunity to explore a variety of disciplines, from Scandinavian literature to ancient Nordic literary traditions to exploring gender roles in Scandinavian society.

“My biggest takeaway was just how intertwined so many different disciplines are with one another,” Lopez said. “And how important it is to consider different perspectives and approaches when exploring certain social or cultural questions or issues.”

GLOBAL VOICES

In addition to opportunities including summer language travel study and the English department’s immersive literary-themed study abroad programs, UCLA’s humanities faculty offer an invaluable global perspective, as embodied by the shared wisdom of the division’s seven newest faculty hires.

Nina Duthie, Asian languages and cultures, studies narrative literature from early medieval through medieval China (220–907 CE), with an emphasis on texts from the northern dynasties. Her current project explores the representation of the Tuoba Xianbei rulers of the Northern Wei state (386–534 CE) through the sixth-century Wei shu, and incorporates issues of mythology, ritual and Buddhist writing. She teaches undergraduate courses in premodern Chinese narrative and fiction, classical Chinese and early Chinese philosophy, as well as the survey course “Chinese Civilization.”

Nina Duthie, Asian languages and cultures, studies narrative literature from early medieval through medieval China (220–907 CE), with an emphasis on texts from the northern dynasties. Her current project explores the representation of the Tuoba Xianbei rulers of the Northern Wei state (386–534 CE) through the sixth-century Wei shu, and incorporates issues of mythology, ritual and Buddhist writing. She teaches undergraduate courses in premodern Chinese narrative and fiction, classical Chinese and early Chinese philosophy, as well as the survey course “Chinese Civilization.”

When did you fall in love with your field?

In retrospect, the moment that I became enchanted with Chinese cultural history was while browsing a tiny shop in Boston’s Chinatown as a teenager and finding a statue of Guan Yin, a female bodhisattva in the Buddhist tradition who embodies compassion. I asked the shopkeeper about her, and though I hadn’t had any exposure to the Chinese language at that time, I wrote down a phonetic transcription of her name, then headed to the public library to delve into this intriguing statue and the exalted status she held in both premodern and everyday Chinese cultural imagination.

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

One motivation for my research into medieval Chinese history-writing is to uncover an understanding of how non-Chinese ethnicities thought about their identity and about how to belong to a tribe that often defined itself in opposition to the earlier, more powerful Han court that ruled the territory of early China. In this regard, aspects such as language, dress and even how skilled one was at riding a horse were all profoundly meaningful. I often reflect on this salient human desire to “perform” one’s cultural identity — a desire which was very much in play for the non-Chinese ethnicities I study.

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

Although my field of medieval Chinese history falls between the two very well-known dynasties of the Han (202 BCE – 220 CE) and the Tang (618 – 907 C.E.) and is comparatively more obscure, almost everyone has heard of one individual who lived during the period of the Northern Dynasties around the fifth or sixth century, and that is the female warrior named Mulan.

Where on Earth inspires you?

New York City is where I attended graduate school, and for me, it will always be a place that I feel is simply overflowing with possibilities for who one can become. The experience of visiting the Metropolitan Museum and viewing the collection of stelae from the Northern Wei dynasty — my own research focus — was always breathtaking.

Dieter Gunkel, classics and Indo-European studies, specializes in the development of ancient Greek, Latin and related Indo-European languages and will be teaching courses on those topics. He is also interested in how language is set to poetic meter and melody, and he is currently researching the relationship between the melody of speech and song in ancient Greek vocal music.

Dieter Gunkel, classics and Indo-European studies, specializes in the development of ancient Greek, Latin and related Indo-European languages and will be teaching courses on those topics. He is also interested in how language is set to poetic meter and melody, and he is currently researching the relationship between the melody of speech and song in ancient Greek vocal music.

When did you fall in love with your field?

It happened in Vienna in the fall of 2001. I was studying abroad there as a junior in college. I had just taken a very intensive introduction to ancient Greek at the Latin/Greek Institute in New York, and wanted to continue taking Greek, so I signed up for a course on “Historical Grammar of Greek,” taught by a wonderful scholar by the name of Martin Peters. The “Grammar of Greek” part sounded right, but I didn’t know why “Historical” was in the title. It turned out to be a course on the development of the language — on the history of the words and the grammar. That was my first exposure to Indo-European linguistics, and I immediately fell in love with it.

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

I spend a fair amount of time closely reading texts that were composed in distant places and times — texts from ancient Greece, Rome and Vedic India, to name a few. To come to an understanding of the texts, you really have to reconstruct the authors’ way of thinking. You find some fascinating differences there, of course, but the vast majority of their hopes, fears, desires and the like are very familiar. I would attribute that mainly to constants in human nature and experience. As for what it means to be human, I don’t know; what do you think?

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

In the same way that Spanish and Italian were once the same language (Latin), English and Hindi were once the same language (Indo-European).

Where on Earth inspires you?

I like to watch a storm roll in over the ocean, but I can’t tell you why.

Allison Kanner-Botan, comparative literature, is a scholar of the literary cultures of early Eurasia, specializing in Arabic and Persian literature of the Persianate world — roughly from the Balkans to Bengal. Her interdisciplinary research extends across the fields of the history of sexuality, madness and disability studies, Mediterranean and Central Asian literary history, and global south studies. She enjoys teaching broad comparative courses that bring into dialogue European and Middle Eastern materials around themes such as love, madness and animality.

Allison Kanner-Botan, comparative literature, is a scholar of the literary cultures of early Eurasia, specializing in Arabic and Persian literature of the Persianate world — roughly from the Balkans to Bengal. Her interdisciplinary research extends across the fields of the history of sexuality, madness and disability studies, Mediterranean and Central Asian literary history, and global south studies. She enjoys teaching broad comparative courses that bring into dialogue European and Middle Eastern materials around themes such as love, madness and animality.

When did you fall in love with your field?

I would say when I first started reading Persian romantic epics in graduate school. Having written about medieval Islamic philosophy for my B.A. thesis, I was struck by how Persian poetics could play with and reimagine the gendered vocabulary of philosophical discourse while still retaining its richness.

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

I hope that my work can speak to the broad question of what it means to love, which is a question of how the self relates to other/others. As a fundamental part of understanding subjectivity, studying love also means studying gender and the body and how we as gendered bodies can act in any given society at different historical moments. Moreover, as someone who studies love, I admire scholarship that attends carefully to political questions of historical discourses on this cross-cultural and trans-temporal phenomenon and yet that remains unfurled by the topic’s popular interest.

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

In the medieval Islamic world, ʿishq — a term often translated as érōs or romantic desire — was thought to be a disease of the brain, which was a notion inherited from Greek humoral theory. However, unlike their Greek predecessors, Islamic physicians such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna, d. 1037) theorized ʿishq as an etiological cause of a severe form of madness (junūn), which underscored the emergence in the 9th century of the literary figure Majnun (whose name, majnūn, or the madman, derives from the same root as junūn). Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine served as a central medical text across Eurasia until the spread of germ theory in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Where on Earth inspires you?

I always like returning to Istanbul — as a central, literal meeting point of Europe and Asia, Istanbul is also a metropolitan city where those from the global north and the global south regularly interact in a way that may even exceed New York City given visa restrictions on travel. I also think Istanbul’s archives and scholarly networks make it a great research center for scholars working on Arabic, Persian, French, Turkish, English or Kurdish.

Anything else?

I enjoy working with students whose research exceeds the confines of my own interests — be that through medieval or early modern studies in different regions of the world, or on aspects of sexuality and madness in different time periods of Persian or Arabic literature, for example. I find that locating meeting points between scholars of different interests and backgrounds is oftentimes some of the most rewarding work in the academy.

Jonah Katz, linguistics, studies the physical and perceptual nature of speech sounds, the way that different types of sounds pattern together in natural languages, and the relationship between these two areas. He also conducts research on the structure and cognition of music and its relationship to language. At UCLA, he will teach graduate and undergraduate classes at all levels on spoken-language phonology, or the nature and structure of linguistic sounds.

Jonah Katz, linguistics, studies the physical and perceptual nature of speech sounds, the way that different types of sounds pattern together in natural languages, and the relationship between these two areas. He also conducts research on the structure and cognition of music and its relationship to language. At UCLA, he will teach graduate and undergraduate classes at all levels on spoken-language phonology, or the nature and structure of linguistic sounds.

When did you fall in love with your field?

It was sometime near the end of my undergraduate degree at the University of Massachusetts, where I’d mainly been focused on a music major. In my final year, however, one of the linguistics faculty took me under her wing and put me in charge of implementing an acoustic speech-production study that she’d been thinking about. I was given a university laptop and use of the UMass phonetics lab, and basically encouraged to do the study as best I could. I remember the thrill of being able to use some of the knowledge I’d acquired in my classes to help design the study and, in particular, conduct acoustic analysis of the materials we elicited. This was really my first contact with the scientific method since K–12, and it was intoxicating.

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

A big part of contemporary linguistics is the search for universal principles of learning, computation or communication that underlie all human linguistic knowledge. Because humans are the only animals with linguistic ability (human languages are categorically different than other animal communication systems), it means that if we succeed in finding such principles, it will tell us something about what makes us uniquely human. A somewhat more peripheral topic in linguistics, but one that I’ve been deeply involved with, is the question of what language shares with other cognitive systems; I’ve been particularly involved in this type of question as it pertains to music, another human cultural universal. So there are big questions about whether things that music and language share are part of some special human endowment for music and language, or whether they reflect more general principles of perception, cognition and computation.

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

In a few of my studies, I’ve tested English-speaking college students on their ability to learn made-up “words” in a made-up “language” in the laboratory. It turns out that, even though most listeners in these experiments don’t think they’ve learned anything at all from listening to a few minutes of nonsense speech, they’re actually able to distinguish “words” that occurred frequently in the study from “non-words” that didn’t occur as often. And they’re even better at this learning task when the “word” units in the language are reinforced by some of the common cross-linguistic sound patterns that I study. Here’s the kicker, though: those patterns are not generally present in English! Meaning that listeners don’t have any evidence from experience that these are useful patterns for discovering words; there instead seems to be something inherent to the sounds involved that reinforces segmentation of the speech stream.

Where on Earth inspires you?

Sardinia has played a big role in my research over the years, and it’s also an extraordinarily beautiful and welcoming place. The Sardinian language is not a variety of Italian: it’s a separate Romance language with a distinct history going back over 2,000 years, though of course there’s been a lot of borrowing and influence from Italian for the last couple hundred. And my work has examined some very famous, tricky and confusing sound patterns in the variety spoken in the south of the island, called Campidanese. I went there to record speakers in 2016, and was welcomed into many Sardinian homes. The island really has rich history, culture and cuisine. And because they see less foreign tourism than many other places in the Mediterranean (especially in the non-seaside towns I was in), people there were genuinely pleased to have a foreign visitor, they were generous about my mediocre Italian and they were really eager to share aspects of their traditional language and culture. I’m hoping to make it back within the next few years to work on a different sound pattern pertaining to vowels, which has also tied linguists in knots for years.

Anything else?

I’m extraordinarily fortunate and very happy to be at UCLA. This is one of the best linguistics departments in the world, and the faculty here are extraordinary scholars. I’m looking forward to seeing what I can bring to the department!

Nancy Alicia Martínez, comparative literature, works on the histories of recorded knowledge, including technologies like writing and books, and how they impact communication across languages and cultures. She focuses on the cultures of Central America and Central Europe from the 20th century to the present, addressing how indigeneity, decoloniality, coloniality and empire influence creative production and its reception.

Nancy Alicia Martínez, comparative literature, works on the histories of recorded knowledge, including technologies like writing and books, and how they impact communication across languages and cultures. She focuses on the cultures of Central America and Central Europe from the 20th century to the present, addressing how indigeneity, decoloniality, coloniality and empire influence creative production and its reception.

When did you fall in love with your field?

There’s a long trail of moments that have encouraged me to keep studying languages and writing with comparative literature, but there are some more recent ones that stand out. I started learning K’iche’, one of many modern Maya languages, the summer before I started graduate school. I was completely unfamiliar with it before, and the distinct differences from the languages I already knew made the task both daunting and exciting. At first, a summer program seemed far too brief for me to start making sense of the language. But by the end of the program, the once unfamiliar orthography could shine through with a new clarity when I read it on the page. It reminded me that connection through language, written or spoken, comes through once we work with the variety of ways that other people make meaning. Working toward understanding a new language is more than just a skill; it’s a chance for connection with other communities and histories.

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

I think in recognizing the universal, we see new value in the specific. My work with Maya and German creative traditions looks to create more dialogue between how the literary traditions of the German world and the multimedia knowledge recording of the Maya world reveal new possibilities for communication. To see variation as exciting difference is to celebrate how the specific circumstances of our time and place cultivate unique perspectives and habits. We learn from those differences, whether that be something like the accordion structure of Maya codices that creates a new reading experience or Ernst Jandl’s sound poetry that reminds us that meaning isn’t only communicated by grammatically correct language, but by the emotions connected to sounds. Humans can be adaptive to difference, and not only afraid of it.

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

Despite common misconceptions, Maya people have been speaking their languages and developing their artistic traditions up to the present. There are over 20 languages officially recognized and spoken in Guatemala alone. Being able to experience some of that rich linguistic variety by working with K’iche’ and its various dialects helps put into focus how personal language can be and the importance of recognizing variation on different scales of use. This can range from regionally specific ones to the unique usage of language by an individual.

Where on Earth inspires you?

I’m always between regions with my work, so I’ll go with two: Copán, Honduras and Vienna, Austria. In Copán, you can visit the remains of a Maya city that continues to be an active site of research. Between the already-visible ruins and the partially unearthed sections, I can’t help but feel excited by the knowledge there is to work with. The histories of the Americas of the precolonial period have been traumatically separated from the Indigenous peoples that continue to cultivate their traditions. Seeing that extensive history of creative and intellectual production continue to be brought to the surface encourages me to learn from and with that knowledge so that it continues to contribute to the present and future.

In Vienna, I work with excavation of a different sort. I like to spend time at the Literature Archive of the Austrian National Library to pore through the manuscripts, correspondences and other ephemera of different writers. Like the ruins in Copán, every slip of paper has traveled through the friction of time to tell stories that were both intentionally and unintentionally recorded. The physical evidence of life and thought is a site to imagine the emotions that accompanied them, to make visceral lives that are no longer here. Getting to go back to the archive and the ruins helps break down the distance that time creates. It’s like continuing a conversation.

Anything else?

Comparative literature as a field often highlights sites temporally and geographically where connection is fostered despite linguistic difference. I encourage anyone who is curious about the world to spend time learning another language. What gets translated is just a glimpse at the rich histories and cultures that have grown with that language, and you’ll be surprised by the new worlds that exist within the nuances of the grammar, vocabulary and modes of expression. Perfect fluency does not have to be the goal; having the chance to listen and share is what makes it worth the effort.

Roberta Morosini, European languages and transcultural studies, investigates Dante and, more generally, medieval and early modern visual and literary culture within a pan-Mediterranean perspective. Her studies revolve around blue humanism, and her teaching and research raise awareness of forced migrations, displacement and slavery of and in the Black Mediterranean. She is teaching courses on Archipelagic-Mediterranean Dante and on Boccaccio and women at the sea.

Roberta Morosini, European languages and transcultural studies, investigates Dante and, more generally, medieval and early modern visual and literary culture within a pan-Mediterranean perspective. Her studies revolve around blue humanism, and her teaching and research raise awareness of forced migrations, displacement and slavery of and in the Black Mediterranean. She is teaching courses on Archipelagic-Mediterranean Dante and on Boccaccio and women at the sea.

When did you fall in love with your field?

I grew up close to the Mediterranean in Salerno, Italy, and with parents who received little education but who bought me and my sisters books, including ones on — this is so dear to me — the masters of medieval and Renaissance painters. Also, my older sister Nunzia, who left us in 2022, loved art and introduced me to the love of bookbinding quires, like in medieval times. She became a book restorer and a paleographer. I was always attracted to painters such Cimabue and Giotto, whose trees are so poetically small and would convey a sense of peace and the promise of something good, as much as I was inspired staring at Piero Della Francesca’s linear vision of a city in these tiny books my parents bought. I would realize only later that imperfect poetry of an “imperfect” perspective would be the very reason that as a student at the University of Federico II in Naples, I would ask my professor of romance philology, Costanzo Di Girolamo, to direct my thesis on knights that save women from dangerous dragons, and would write my thesis on Marie de France’s Fables, in particular the fables with human characters. I guess the attraction to imperfection is an acceptance of being human.

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

I answer with something Dante uses in his poem, the Commedia: as he is in the dark wood, first he tells us that he does not know how he got there, then when he looks back at the dark wood, he says that he feels like he almost shipwrecked. What Dante does is to first and foremost accept the human condition: he is not perfect, and he is accountable as he admits his fragility, the acceptance of uncertainty, of a nonlinear time and a nonlinear space, and to trust Virgil, who represents reason.

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

The one I cherish the most is related to the first semester I taught in Italy, at the L’Orientale di Napoli. I was teaching a course on women and geocritical transgressions in Boccaccio’s Decameron to freshmen. Two students came to see me; one had drawn a portrait of me while I was teaching: Black, with a lot of curly hair. The other thought she never wanted to be a teacher like her mother. They came to see me to tell me: “You remind me of a Brazilian activist, and now I want to be a teacher myself.” I cannot deny that a tear of joy came along my face.

Where on Earth inspires you?

The South — the Italian south within the global south of the world; that is where I am proudly from. I believe that coming from a small town in southern Italy has shaped me in and out of the classroom to be intentionally committed to give voice to those who don’t have any, the underrepresented, to study women dressed as men to be able to cross the sea, women slaves, Muslim and Christian girls traded in the medieval Mediterranean. There is so much work to do when it comes to shaping an intentionally inclusive society, and it starts in class, bringing literature back to society.

Anything else?

Related to bringing the local into the global here at UCLA, I want to say thank you. It is moving to see how the UCLA CMRS Center for Early Global Studies and the UCLA Division of Humanities cherish my story; here I feel part of a larger story, where each story counts. My commitment is to keep moving and contribute to sharing the passion, as we shape global citizens aware of other spaces and other voices — since, as Frantz Fanon says, “we are the other.”

Vetri Nathan, European languages and transcultural studies, studies a range of subjects, from the cultural foundations of environmental justice — and injustice — to national, racial and diasporic identities, particularly but not limited to Italy and the wider Mediterranean region. He is the founder and director of the Cybercene Lab, a new humanities lab that will start up at UCLA in the coming year. The lab is envisioned as a gathering space to study multispecies well-being, healing and habitability, the connections between cultural discourse in a digitally connected world, manufactured conflicts, climate change and habitat and biodiversity loss. His courses will explore various topics, such as Italian and global food studies, Black and migrant Italy and the multispecies humanities.

Vetri Nathan, European languages and transcultural studies, studies a range of subjects, from the cultural foundations of environmental justice — and injustice — to national, racial and diasporic identities, particularly but not limited to Italy and the wider Mediterranean region. He is the founder and director of the Cybercene Lab, a new humanities lab that will start up at UCLA in the coming year. The lab is envisioned as a gathering space to study multispecies well-being, healing and habitability, the connections between cultural discourse in a digitally connected world, manufactured conflicts, climate change and habitat and biodiversity loss. His courses will explore various topics, such as Italian and global food studies, Black and migrant Italy and the multispecies humanities.

When did you fall in love with your field?

I study and teach how global cultural identities and formations (nationhood, race, migration, gender, et cetera) shape our lives, and also how humans relate to the natural world and to other species of life on this planet. My parents cultivated my love and curiosity for both culture and nature by taking us for trips to experience the historical, natural and cultural riches of India as a kid, even though they didn’t have enough money for any “fancy” travel. My love for cinema stemmed from coming from Mumbai — the hub of Indian filmmaking — and from my mom’s habit of taking us for late-night trips to movie theaters. Then, in my high school junior year, I was introduced to an amazing way of seeing the world through literature by my talented English lit teacher. Now, I wish that all kids may have the good luck of getting such amazing parents, teachers and mentors in life!

What can your work help reveal about what it means to be human, regardless of time or place?

My work studying and analyzing how human societies globally use or misuse “culture” to constructive or corrosive ends reveals both some amazing and some terrible qualities about us humans. My newer work, especially through my new lab, seeks to press the humanities to look beyond the restricted limits of the species “homo sapiens,” and understand how we are intimately intertwined with “more-than-human” lives (plants, animals, fungi, microbes, et cetera). I am realizing that to truly understand humanity and our future as a species, we simply cannot continue to ignore our multispecies connections to the rest of life and the ecosystems that make us who we are.

What’s your favorite fun fact about your field?

My research takes me to different parts of the globe and gives me the privilege of bringing back all that energy and perspective to campus and to the classroom! I love introducing my students to the wonders of global culture: for example, I co-taught with a chef a food culture study abroad course in Italy for many years, and hope to restart such a course at UCLA. In this class, we cook constantly, we eat constantly and take a deep dive into the history of everyday Italy from the ancient Romans till today. I often have been told by many students that this was a life-changing experience for them. That is quite humbling to hear! It is also a privilege to be a visibly brown professor of European studies and to bring to the classroom the challenges and opportunities that this presents. It is a big responsibility and joy to represent the true diversity of what Europe is and can be — much more exciting and interesting and far beyond the limited stereotypical or “touristic” idea that is so prevalent both inside and outside Europe.

Where on Earth inspires you?

My first love is Italy — Rome, probably. To experience millennia of history all layered and scattered throughout the guts and skin of a city is to experience bliss. It is the closest we can get to time travel! My second place of inspiration are the vast natural landscapes of the American West. I feel like I am home when I am on this side of the Mississippi. I don’t know why…it just is!

Anything else?

This is my first year at UCLA and I cannot wait to meet and get to know everyone. I love America’s universities, and especially its public universities. I also believe that the humanities are the foundation of much that is just, sustainable and democratic in any nation, so I am very proud and happy to play a small part in supporting its important mission.

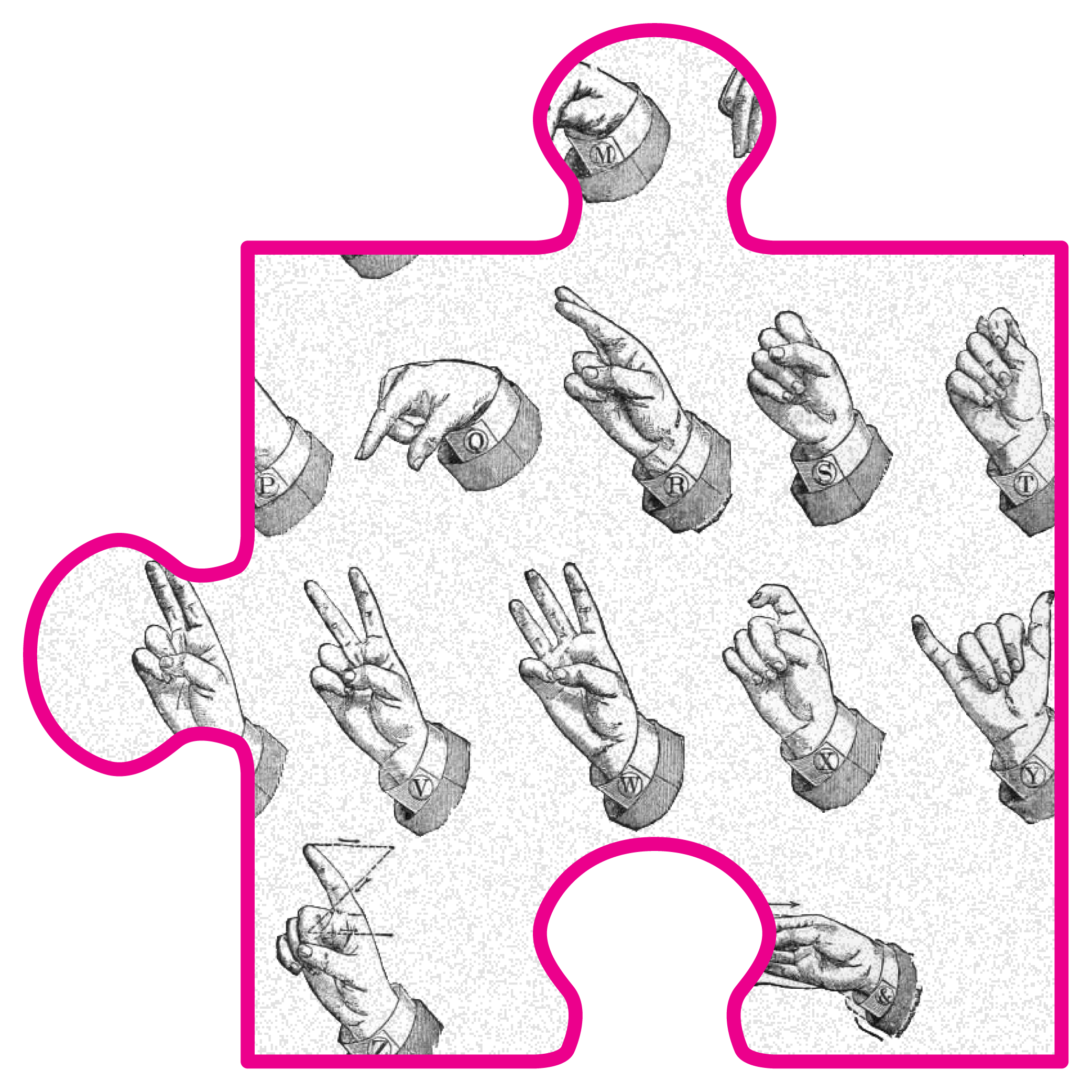

WINGS TO FLY

This year, UCLA hired a second ASL instructor, Jennifer Marfino, to join the existing team of instructor Benjamin Lewis and interpreter Mariam Janvelyan. We asked Marfino to share her thoughts.

Jennifer Marfino photographed by Damon Cirulli

What makes ASL such a special and impactful language to learn?

ASL is such a unique and powerful language because it goes beyond just words — it’s a visual language that incorporates facial expressions, body movements and even personality. Many people don’t realize how much knowing ASL can mean to the Deaf community. For example, something as simple as a cashier knowing a few signs can instantly brighten my day. I once had an experience where I was hit by a car, and the relief I felt when a firefighter knew some ASL was indescribable — it truly made me feel safe in that moment of crisis. This is why I’m so passionate about teaching ASL. The potential for my students to make a difference in fields like health care and education is huge, especially in bridging communication gaps and creating a more inclusive world for the Deaf community. UCLA offers an amazing platform to spread this knowledge and foster understanding about Deaf culture and ASL.

What should everyone know about the nuances of sign language?

Like spoken languages, there are regional differences. For example, signers in the Northeast tend to sign faster, while those in the South sign slower — kind of like having different accents or styles. Not everyone signs the same way, which makes it all the more interesting!

What does travel mean to you?

Travel, to me, is a form of therapy. It allows me to step away from the routine of daily life and immerse myself in new environments, cultures and experiences. There’s something incredibly healing about exploring unfamiliar places, meeting new people and learning about different ways of life. Travel pushes me out of my comfort zone and offers perspective, reminding me of how diverse and interconnected the world really is. Whether it’s the excitement of discovering a new city or the peacefulness of being in nature, travel helps me recharge, reflect and grow in ways I never could if I were to stay in one place. It’s a way to reset both mentally and emotionally, and I always return home feeling more grounded and inspired.

What’s your favorite travel adventure thus far?

One of my favorite travel experiences was in Chile, where I learned Chilean Sign Language before going. I had the chance to connect with the Deaf community there and even gave a presentation on improving accessibility for people with disabilities, especially those who are Deaf.

Anything else?

If there’s one thing I could leave everyone with, it’s this: learn ASL. You have the potential to change someone’s life, and you won’t regret it!

A WORLD OF COLLABORATIONS

Pin-Hua Chou

Another interdisciplinary effort spanning the divisions of humanities and social sciences — and the globe — came when history doctoral student Pin-Hua Chou was able to complete an internship in Taiwan’s Fubon Art Museum, thanks to the Maggie and Richard Tsai Endowed Fellowship.

“Honestly, I don’t think the differences between these two disciplines of humanities and social sciences are as vast as imagined. We both need to study a large number of historical materials, only the materials we focus on differ,” said Chou. “Since my research is on the history of museums, my work is highly interdisciplinary. The overlap between art history and history is inevitable; I need to examine the interpretive history of many objects in museums, the context of the era in which they were produced, the provenance research, etc. The artists/authors and the subsequent storytellers (curators or researchers) all become subjects of my research.”

What did this opportunity mean to you?

Though my internship was brief, I could sense that Fubon Art Museum has the potential to connect you to the world. It is located in the bustling heart of Taipei and was designed by world-renowned architect Renzo Piano. Since its opening in May this year, it has hosted numerous world-class exhibitions, including those of Rodin, Van Gogh and Susumu Shingu, and it is set to feature exhibitions by several female artists soon. The museum’s hardware and software are impressive, with global connections and collaborations with institutions from all over the world. What stood out most to me was that, while they strive to bring the world into Taiwan, they also aim to share the stories of Taiwanese collections with the world, which is the most exciting aspect I gained from this experience.

The main purpose of my internship at Fubon Art Museum was to assist the museum with collection research. It meant so much to me, as a Taiwanese, to be able to learn about these collections in such an important, newly built Taiwanese institution. This allowed me to understand the context of these collections within Taiwan, Asia or even the world, and what kind of dialogue they can create in these contexts, which was extremely important to me. Although my research isn’t directly related, the regional and temporal aspects, as well as the artists’ transnational experiences and self-identification, all complement my work. I was glad to be able to use some of my expertise to assist the museum, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to broaden my research directions through this experience.

What sparked your interest in your field?

My parents were history teachers, and since they volunteered at the National Palace Museum in Taiwan every weekend when I was a child, I practically grew up in the museum. When I reached high school, I also became a youth volunteer at the National Palace Museum, guiding tours. Perhaps influenced by my parents, I eventually majored in history in college. When I decided to pursue further studies in graduate school, museum studies naturally became my first choice. My love for museums has never faded, and I have always hoped to work in one. A significant turning point that led me to my current research came during my time in the museum studies program, where I was fortunate to receive an internship opportunity. This allowed me to participate in exhibition planning at the Muséum Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle and Musée de l’Homme in France. During this opportunity, I became interested in the history of France’s anthropology museums and the history of anthropology as a discipline. So, when deciding on the direction for my Ph.D. research, I resolutely returned to the history department, aiming to study the history of museums, the history of knowledge generated through museums, and the people associated with museums.

What does taking a global perspective mean to you and your work?

Initially, my research theme focused on the history of France’s ethnographic museums, but as time went by, I realized that ethnographic museums are deeply linked to imperial colonialism. Anthropology and ethnology as disciplines are also closely tied to France as an empire. So, if possible, I should pay more attention to the transnational experiences that were happening at the time, and the dynamics that existed in the relationship between the colonies and the metropole, or even between the colonies. This isn’t merely a mission of a single nation-state, but rather as part of a larger, interconnected world. In my research at Fubon Art Museum, adopting a global perspective helped me re-examine the collections, reassess the complicated context of the artists, and understand Fubon’s relationship with the world as a Taiwanese institution.