Bruin Bookshelf Spotlight: Professor George Baker

‘Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography’ by George Baker, UCLA professor of art history

By Álvaro Castillo | February 15, 2024

When George Baker was asked to write an essay on photography for an exhibition in 2008, unbeknownst to him, he had begun the journey toward completing “Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography.” In it, the UCLA art history professor sets out to investigate how a generation of women artists is invigorating photography in the age of digitization by returning to earlier, incomplete or unrealized moments in the field’s history.

For the first installment of the new UCLA College Q&A series, Bruin Bookshelf Spotlight, we spoke with Baker to get a snapshot of the approach and inspirations of his latest work, how a resurgence in analog photographic techniques is expanding the landscape of modern photography and why the arts at UCLA and across Los Angeles continually inspire Bruins.

What inspired you to write this book?

I have been an active art critic for almost 30 years, and have been having longstanding dialogues with contemporary artists. Many are now friends who challenge me with what they are making, what they are reading, what they are thinking about in the culture today. These dialogues were the direct impetus to the writing of this book.

An artist with whom I am close, Paul Chan, sent me an essay to read by the philosopher Theodor Adorno on the “late style” of the composer Beethoven’s final works. Why was my friend inspired by this difficult text? It was motivating a series of his new pieces. Then, when I read the essay, I found immediately that it connected to the writing I was doing on tracking and understanding changes in how contemporary artists use photography. The critical idea of a cultural “lateness” seemed to align with the situation of photography now.

And that is the other inspiration for the book: photography itself.

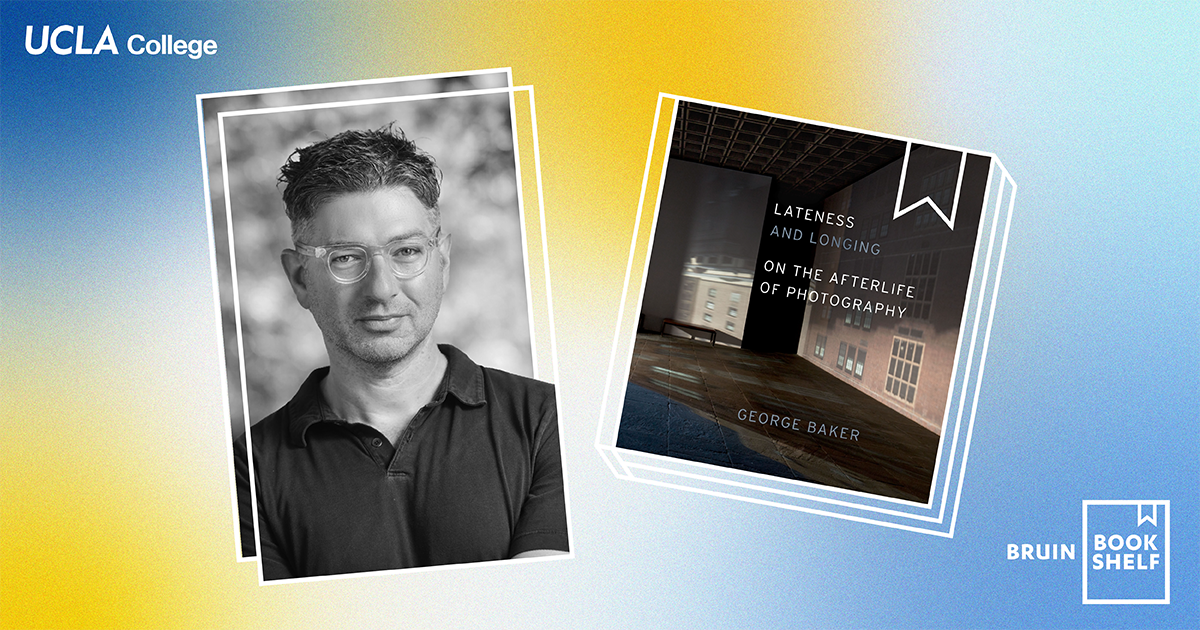

Zoe Leonard / Whitney Museum of American Art

In a 2014 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Zoe Leonard transformed a section of the Museum’s fourth-floor gallery into an immersive camera obscura.

Photography has never been more a part of our daily lives; almost all of us carry sophisticated digital cameras in our pockets everywhere we go. Yet there is the wide-ranging understanding that, perhaps, the old ideas around photography have now “died,” and that we have lived through a fundamental change in what photography is and can be.

I wanted to write a book that, in a strange and counterintuitive way, would dive into the changes around photography we have been living through. I wanted to write a book on artists who continue to use the old analog photographic techniques, but use them in paradoxically new, even radical ways. I wanted to understand photography and how it is being altered, transformed and expanded today. All of the art projects explored deeply in my book are made by women artists; there is a feminist story here about photography too that I wanted to explore, a critical use of photography that is essentially new.

How does “Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography” fit into the ongoing conversation around photography?

My book hopes to be in a dialogue with the many extraordinary texts that are generally understood to amount to the “theory of photography.” The writings on photography by philosophers and critics from the past, like Walter Benjamin or Roland Barthes, are central and my book hopes to move the conversation on photography forward from their ideas.

And I lean on a series of thinkers and books that are not themselves about photography, but allowed my thinking to develop in this realm, For example, Edward Said’s last unfinished book on “lateness” and late style, the extraordinary literary critic Svetlana Boym’s “The Future of Nostalgia,” classic cultural texts like Susan Stewart’s “On Longing,” ideas from recent art criticism such as Hal Foster’s notion of cultural “aftermath.” These writers and books, among others, form what I would call the productive constellation from which this book emerges.

Can you share any memorable anecdotes of writing this book?

This book had a long gestation. After beginning my dialogue with my artist friend, I was asked to write an essay on photography for an exhibition in Italy. To date this moment: I was at the opening celebration for this exhibition the night President Obama was first elected. At the opening dinner that very night, three Italian art critics whose names I had known since I was myself a student in college were seated at the table with me. They all agreed when one of them turned to me and said, perhaps sarcastically, that the (long) essay I had written for the exhibition catalog should really be a book. Slowly, it dawned on me that I should listen to them. Over years, while I worked on other projects, the book took shape in intense bouts of writing, mostly during my breaks from teaching at UCLA.

With a long writing process like this, I have many anecdotes I could share. Actually, I weave some stories about the process of my writing into some of the chapters in the book, especially the last chapter on an artist named Moyra Davey, who writes as much as she photographs, both often in a diaristic style. I believe quite often that writing insightfully about contemporary art involves entering into dialogue with the art about which you are writing — I resist the fantasy of academic “objectivity,” or writing in a more distanced way about art.

“It is said you don’t really know what you are wishing for sometimes, until it befalls you — that is how I feel about having arrived at UCLA as an art historian, art critic and teacher.”

—GEORGE BAKER

In this chapter, I confess all the many things that were happening to me while I was writing the text. I wanted some of the moments from everyday life to rhyme with ideas about photography — accidents that happen to you, chance events, sudden revelations, all of which have long been linked to the way we think about what a photograph itself is. And so I found myself writing about the birds that visited my study’s window, scratching at the screens and the old idea of augurs and the omens such chance encounters might entail.

On a walk I took while taking a break from writing, I ran into something extraordinary: a nest of baby owls in a platform carved by birds into the top of a palm tree in a park near my home. I had never seen such a thing before. I visited these birds, this palm tree, every day while writing this chapter. By the end, just as I was about to finish, I came back to find the baby owls were now all gone, except for one left behind, on the ground, struggling to learn how to fly.

However strange this sounds, the chance events, the old ideas of superstition and almost magical occurrences — these inspired new insights in the writing at that time, insights into photography.

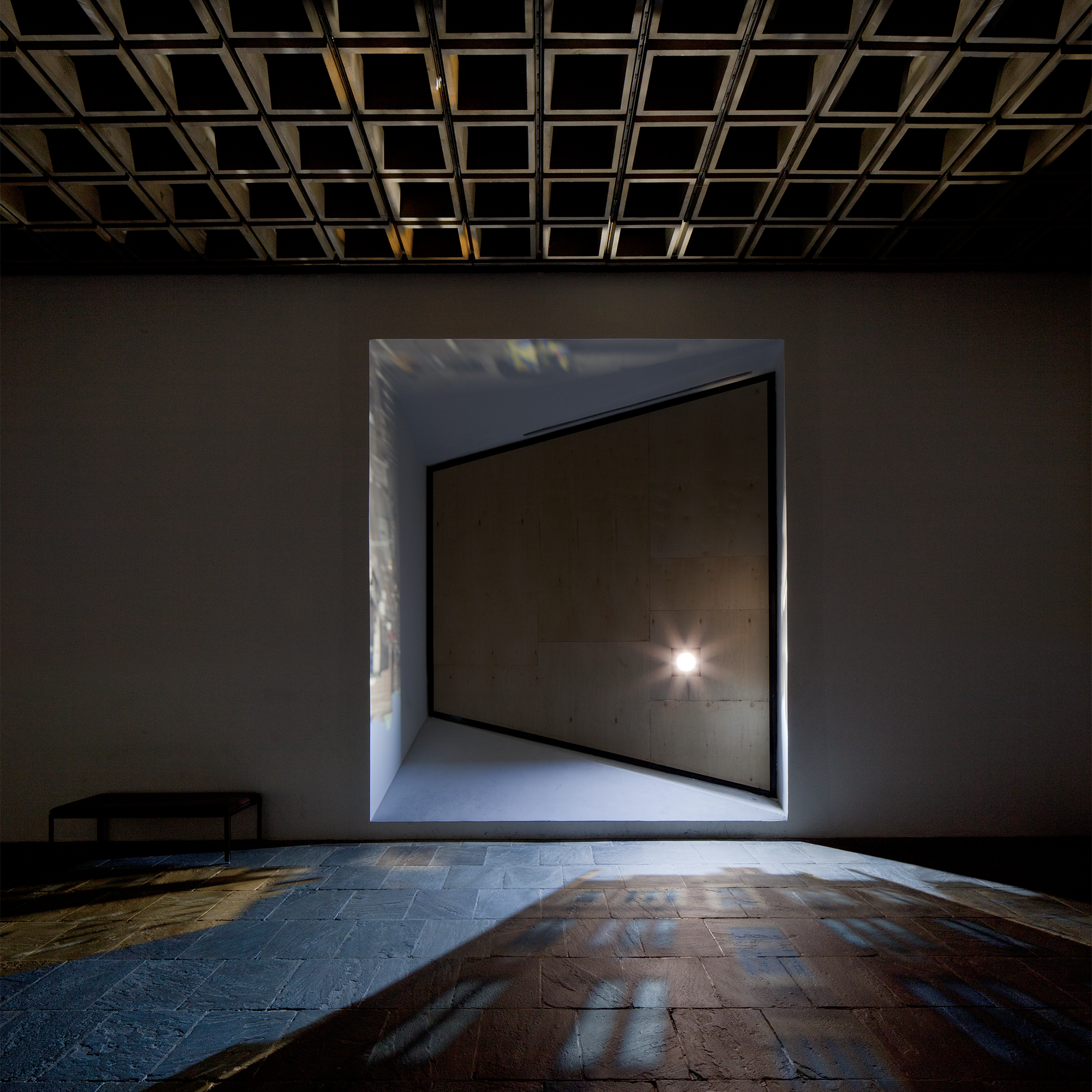

Tacita Dean / Frith Street Gallery

Featured artist Tacita Dean’s 2011 “FILM” is a montage of black-and-white, color, and hand-tinted images. It used in-camera and studio techniques such as masking, double-exposure and glass matte painting.

What role has the UCLA College played in your research and scholarly work on photography?

For 20 years, the UCLA College has been the testing ground for my thinking on photography. I regularly teach its history as one of my main lecture courses and offer smaller seminars on photography for undergraduates, graduate students and art students alike. UCLA is also a “photography” university and Los Angeles, similarly, a photography town. What I mean is that when I arrived at UCLA, I found myself immediately inserted into a community of major thinkers and artists, themselves teaching photography. And I had little idea — until I moved to Los Angeles — how passionate the photography community in this city is.

It is said you don’t really know what you are wishing for sometimes, until it befalls you — that is how I feel about having arrived at UCLA as an art historian, art critic and teacher. This place has grounded, supported and transformed my work in ways I am sure I do not even myself fully understand.

Is there anything Bruin art aficionados should consider about UCLA?

Take in everything UCLA has to offer in the realm of the arts. Go to the Hammer and the Fowler. See all the shows. Visit the student exhibitions on the campus — the work is often extraordinary. Duck into the Luskin Center and walk the ground floor hallways, filled with art by UCLA teachers and artists. Take in the contemporary art institutions around the city.

Or start more simply: get yourself to the UCLA Sculpture Garden. Discover all its secrets. It has secrets! The students at UCLA have taught me many of them over the years.

What projects will you work on next?

Lately, I have been writing a series of essays on contemporary painting. I am writing currently on the work of a Russian-born painter named Sanya Kantarovsky, whose work no one really understands yet, but many seem to agree is a major new figure. I am trying to figure out why the work is so compelling — this is the existential crisis of the art critic, the leap into the unknown, the imperative to find language to bring new artworks into a provisional understanding.

After this project, I will spend some time on a visiting fellowship pondering and researching the “artist’s artist” Paul Thek (1933-1988), another painter but also major sculptor. I worked a decade ago on the first U.S. retrospective given to Thek, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. But like my photography project, the essay I wrote then always seemed to me something that should become a longer book. Thek expatriated from the U.S. after the 1960s, at a point in time when he was briefly as famous as Andy Warhol. He moved to Italy and the work completely changed. I am exploring the ways in which Thek confronts the culture of the Italian South, popular culture and working-class culture.

There is a story here that I find fascinating — a cultural encounter by an American queer artist that opens up new ways for art to be political, to engage new audiences, to define its place in a “culture.” In the late 1960s, Thek wound up living and working on an island in the sea between Rome and Naples called Ponza. It shows up in all his work. I had the opportunity this past summer to travel to the island, on the trail of Thek. There are still families there with whom he lived, figures with whom he worked, paintings and artworks he left behind. It felt like being on the trail of hidden treasure, a joyous period of research now begun.

Follow George Baker on Instagram.

If you are a member of the UCLA College community who has published a book, tell us about it.