Exhibition puts viewers in midst of WWII-era removal of Japanese Americans

‘BeHere / 1942,’ presented by the Yanai Initiative of UCLA and Tokyo’s Waseda University, opens May 7

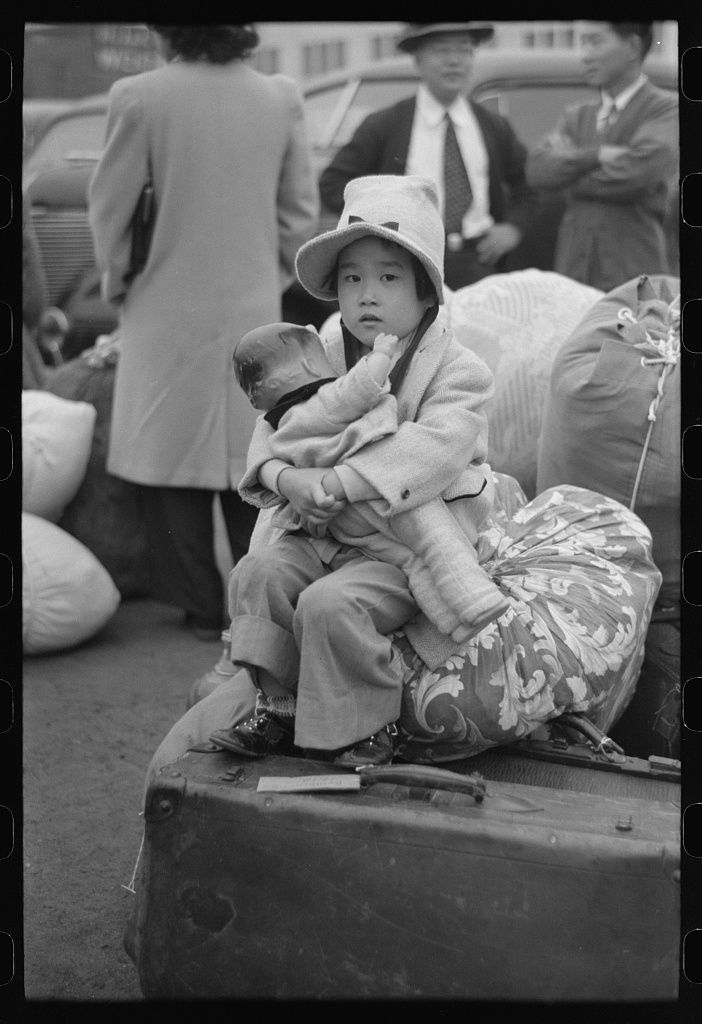

Cameramen record Michi Tanioka, 5, as she waits to be sent from Los Angeles to the Manzanar prison camp in April 1942. This image, taken by photographer Russell Lee, and others by Lee and Dorothea Lange documenting forced removals along the West Coast were used as inspiration for Masaki Fujihata’s immersive AR re-creation. Image credit: Library of Congress/Russell Lee

By Alison Hewitt | May 2, 2022

Eighty years ago, during World War II, the U.S. government forcibly removed Japanese Americans from the West Coast, incarcerating 120,000 in concentration camps. This May, an exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum lets visitors step into those dark days of 1942 through an augmented reality re-creation at the very site where thousands of Japanese Americans living in downtown Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo neighborhood were ordered to report before trains and buses took them to the camps.

“BeHere / 1942: A New Lens on the Japanese American Incarceration,” which opens May 7, is presented by the Yanai Initiative for Globalizing Japanese Humanities, a joint project of UCLA and Japan’s Waseda University, in collaboration with the museum.

The brainchild of pioneering Japanese media artist and former UCLA visiting professor Masaki Fujihata, the exhibition draws on thousands of historic photographs of the 1942 removal, including many taken by government-employed photographers Dorothea Lange and Russell Lee.

While Fujihata incorporates scores of these images into his exhibition, he also reexamines and transforms them to shed new light on the dynamics of the expulsion tragedy. He reimagines some as AR videos and hyper-enlarges others to reveal for the first time the reflections in subjects’ eyes, allowing visitors to see what they saw: reporters and government officials hovering just outside the frame.

“This is an exhibit about what photographs reveal and what they conceal,” said UCLA Professor Michael Emmerich, director of the Yanai Initiative. “On one level, it is about what happened here in Little Tokyo and all along the West Coast in 1942, but it is also about the present. Even 80 years later, we are still grappling with anti-Asian violence and racism and still dealing as a society with the same civil rights issues.”

Opening during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, “BeHere / 1942” launches almost 80 years to the day — May 9, 1942 — that 3,475 residents of Little Tokyo lost their homes, their possessions and their freedom. It was among the largest of the wartime Japanese American removals. About 37,000 Los Angeles residents of Japanese descent were incarcerated, including many who departed in April 1942 from the former Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, now known as the Historic Bulding on the museum’s campus.

A behind-the-scenes look at the making of the AR re-creation in Los Angeles | By David Leonard

In the museum’s outdoor plaza, facing the historic temple building, visitors can use smartphones (with the “BeHere / 1942” app) or museum-provided devices to view Fujihata’s massive 200-person AR installation. By aiming their device at the building and nearby spaces, they’ll see a series of historically inspired 3D videos overlayed on the physical environment, recreating a scene like the one that occurred May 9 and up and down the West Coast. The installation will remain visible even after the exhibition concludes on Oct. 9.

Drawing inspiration from the photographs of Lange and Lee, the digital re-creation involved dozens of volunteer “actors” in both Los Angeles and Tokyo who donned period costumes — some even got 1940s-style haircuts — then entered special film studios to have their likenesses recorded through a new technique called volumetric video capture and integrated into the AR app. Three of these volunteers were among those sent to the camps in 1942, including Michi Tanioka, 85, who was expelled from Little Tokyo with her family as a 5-year-old.

Left: Michi Tanioka, 85, participating in the augmented reality re-creation. Image by Masaki Fujihata. Right, Tanioka at age 5, waiting to be sent to a prison camp. Image: Library of Congress/Russell Lee.

“It was a major part of my young life to be taken away at that age,” said Tanioka, who recalled spending many years ashamed of her imprisonment before becoming a docent at the museum. “My family was just starting to have a better lifestyle, but then all of that stopped. After 9/11, I saw the same thing could happen to others if we weren’t vigilant and outspoken. Hopefully this exhibit sends the message that nothing like this should ever happen again.”

Tanioka was also among those photographed during the removal. A picture of her clutching a doll while a Japanese woman, possibly an interpreter, kneels next to her and two white cameramen record her is featured on the exhibition’s catalog. Fujihata used this image for reference in one of his AR scenes. He reviewed dozens of photos to depict one such moment frozen in time, with the camera panning to reveal the intimidating scene Tanioka and other children encountered.

The exhibition also encourages visitors to put themselves in the photographers’ shoes by imagining they’ve been dispatched to document the removal. Inside the museum is a smaller AR installation, a re-creation of downtown Los Angeles’ Santa Fe train depot from which Japanese American residents were sent to the camp at Manzanar. The scene is viewable only through specialized replicas of the Graflex camera used by Lange, and the installation displays pictures visitors take.

“I tried to understand how these photographs were made — the relationship of the subject and the photographer — and to find ways to look at these pictures, not just as a consumer of the image but from the perspective of the person behind the camera,” said Fujihata, who conceived the exhibition while a Regents’ Professor at UCLA in 2019–20. “When a cameraman came and asked to take your photograph, you couldn’t say no, especially in a situation like the forced removal, over which you had no control. There was a clear hierarchy then, as there is now, with the camera becoming a sort of weapon.”

This dual perspective invites deeper engagement with the removal and incarceration, inspiring deep sympathy with those being incarcerated while at the same time forcing visitors to see through the eyes of the photographers — some of whose photos, like Lange’s, so deliberately invoked the injustice that they were censored by the government.

Using new technology to teach about the forced removal and incarceration is a vital way to communicate about the importance of civil rights, especially after the survivors are gone, said Ann Burroughs, president and CEO of the Japanese American National Museum.

“It has been 80 years since people of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from their homes in Little Tokyo, yet issues of racism, discrimination and exclusion remain starkly present,” she said. “The need to advocate for inclusion and social justice remains urgent. By combining our historic knowledge with new and innovative technology to tell these important stories, we honor this legacy and help to reimagine a just future.”

Read more about the Japanese American removal and incarceration on UCLA Newsroom:

► A lesson in state-sanctioned injustice

► Understanding today’s anti-Asian violence by looking at the past

► Documentary explores the site of the Manzanar camp

► Bruins imprisoned in camps return 70 years later to receive degrees

‘I know I have civil rights’: How the incarceration resonates today

June Aoichi Berk (far right) with her family at the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, where they were incarcerated. Image courtesy of June Aochi Berk

June Aochi Berk, now 90 and a docent at the museum, vividly recalls preparing to go to the camps 80 years ago. Her parents and neighbors had a few days to sell most of their belongings, and, fearing arrest as they saw community leaders taken away, they built backyard bonfires to destroy family heirlooms suggesting connections to Japan.

“My older sister was very upset, and I remember she said, ‘I know I have civil rights. They can’t do this to us. We’re American citizens,’” said Berk, who participated in the AR re-creation. Though she used to avoid discussing her past, she now speaks about the incarceration to groups of students, many who have never heard of the camps or only know about them from a single paragraph in history books.

“When you start to blame people for where they come from, we get into very dangerous territory,” Berk said. “I’ve never been to Japan. There was nothing my family could have done to stop the war. American Muslims didn’t cause 9/11. American Russians didn’t invade Ukraine. We have to speak out, because when one person’s civil rights are taken away, everyone’s civil rights are diminished. This exhibit reminds us to be vigilant so nobody goes through this again.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom. For more news and updates from the UCLA College, visit college.ucla.edu/news.

Image credit: Library of Congress/Russell Lee

Image credit: Library of Congress/Russell Lee

UCLA

UCLA