A bird’s-eye view of history

Iconic aerial photo archives from the UCLA Department of Geography are a rich resource for researchers and the public

UCLA Geography Aerial Archives

By Jonathan Riggs

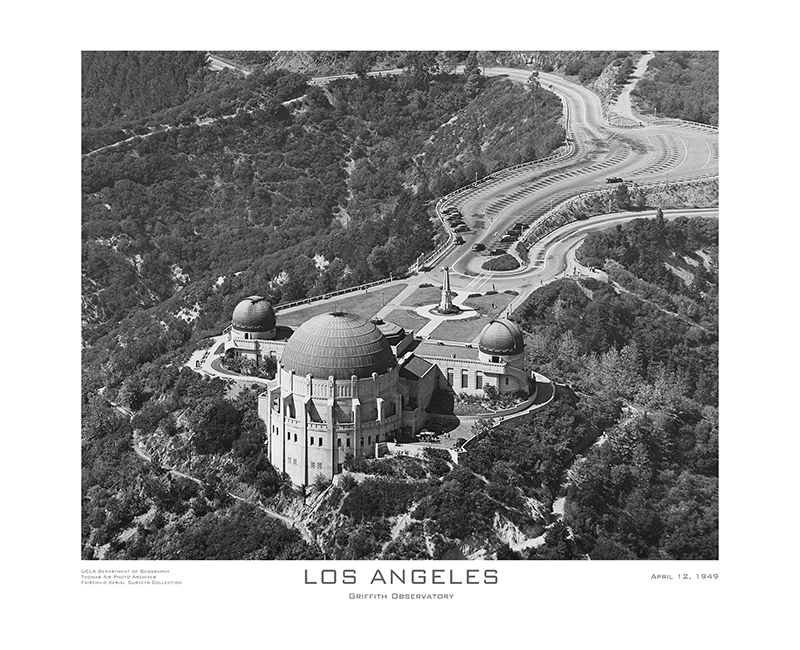

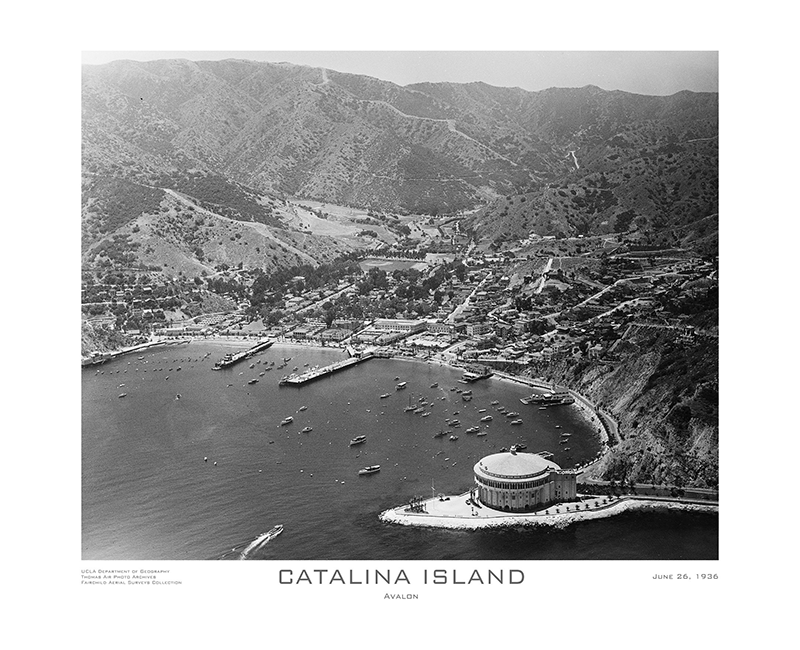

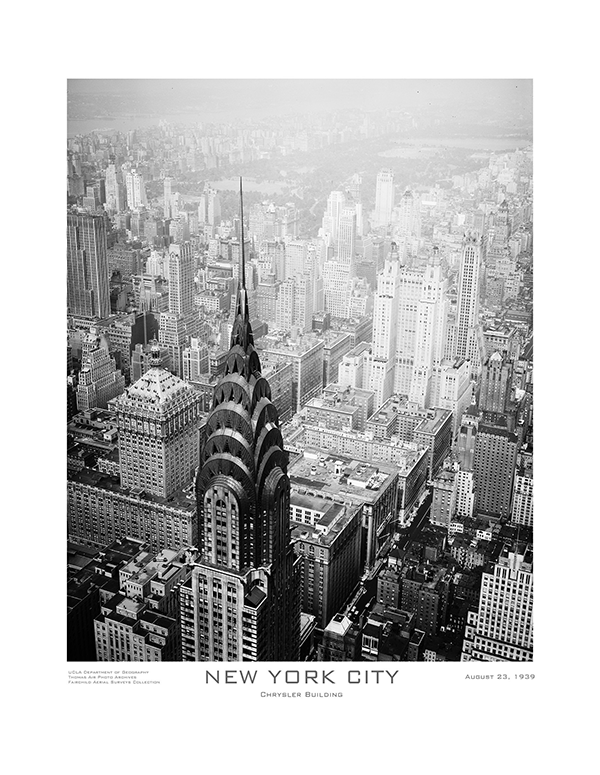

Today, anyone with a drone can capture dazzling images of the Earth below. But it wasn’t so long ago that would-be aerial photographers had to swing nearly 50-pound aerial cameras out of single-engine plane windows to do the same. The UCLA Department of Geography owns a huge number of such images in its Benjamin and Gladys Thomas Air Photo Archives, many of which detail California life and landscapes as far back as 1920. These remarkable images are as valuable artistically as they are historically.

In fact, the department has launched a new website featuring images from two of its collections, which are among the world’s best. Breathtaking images of Los Angeles and New York City—everything from a gorgeously moody shot of clouds over Manhattan on Oct. 15, 1931 to a view of UCLA and Westwood on Jan. 13, 1950—are available to purchase as fine art prints.

“The department was given these collections and has been maintaining them as best as possible for decades. However, some of the negatives are now over 100 years old and deserve better long-term treatment than we can give them,” says department chair Greg Okin. “Proceeds from the sale of images will allow us to preserve the physical images for posterity. It will also allow us to digitize them in order to ease access to the collection for generations to come.”

Overall, the Aerial Archives contain 120,000 black and white negatives, 100,000 black and white prints, and several hundred color images. What makes these collections so special is that they are exclusively oblique aerial photos, meaning they were taken from the side, rather than looking straight down as on a Google map. This angle captures a richness of detail that allows viewers to read signs, identify specific cars and even see what people were wearing.

UCLA Geography Aerial Archives

In addition to bringing the past to vivid life for members of the public, these archives are an incredible scholarly resource.

“We have students and faculty across the university as well as people in many industries who use this unique resource for their research,” Okin says. “We can see, for example, the development of the Los Angeles River as it was channelized. We can identify areas of beach erosion. We can see how specific areas of Los Angeles have changed through time. We can see how the city developed into the complex place that it is now as well as map the legacies of policies and attitudes in the region. The potential uses are endless.”

Another devoted user of the Archives is Kelly Turner, assistant professor of Urban Planning and of Geography and co-director of the Luskin Center for Innovation. She’s leading a multifaceted project to explore how the racist policy of redlining—and hundreds of other seemingly unrelated and everyday actions by homeowners and developers alike—caused the L.A. neighborhood of Watts to become nearly 5 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the overall city average.

“Our project aims to use innovative, interdisciplinary methods to say what land change occurred, why and how much it changed the temperature,” Turner says. “We hope to arm the community of Watts with data, and to enable them to pinpoint specific elements that can be effectively changed.”

UCLA Geography Aerial Archives

Turner and her team, which includes anthropologist Bharat Venkat collecting oral histories and historian Marquis Vestal with expertise in the intersection of race and land transactions, are using the Archives to create a painstakingly accurate model of historic Watts over the years. By simulating the built environment so accurately, they are able to replicate the past microclimate conditions and determine how the temperature felt for the average citizen on the street on a given day.

“This project wouldn’t be possible without these archives. We need to know the exact placement of features like walls and sidewalks to build the model,” Turner says. “This high resolution imagery allows us to revisit a place with methods that were not available in the 1920s or ’50s to glean new insights that are relevant to contemporary debates about heat and environmental justice.”

“Archival photos reveal the history of planning decisions,” adds Tiffany Rivera, an urban and regional planning graduate student who is assisting on the project. “I look at these images to inform more sustainable and equitable urban designs.”

It’s fitting that these collections landed at UCLA: Los Angeles was a nexus for early aerial photography, and early motion pictures used aerial photography starting in the 1920s. These two iconic industries essentially grew up together just a few miles from campus, making the Archives especially meaningful for the UCLA community.

“We invite anyone interested to check out this incredible world-class resource, either on our website or to reach out and make an in-person visit,” says Okin. “It’s a remarkable opportunity for everyone to see what the collection, and UCLA, have to offer while also providing the chance to own beautiful pieces of history.”

For more of Our Stories at the UCLA College, click here.

UCLA Geography Aerial Archives

UCLA Geography Aerial Archives

Photo by Fotoreserg

Photo by Fotoreserg