‘I could be killed at any time’: The anguish of being wrongfully convicted of murder

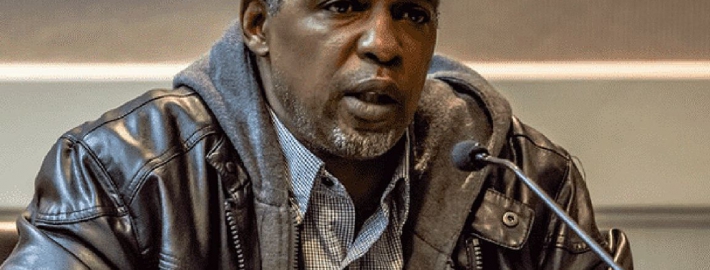

Maurice Caldwell. Photo credit: David Greenwald/The People’s Vanguard of Davis

By Stuart Wolpert

Maurice Caldwell spent 20 years in prison before his wrongful conviction for a 1990 murder in San Francisco was finally overturned.

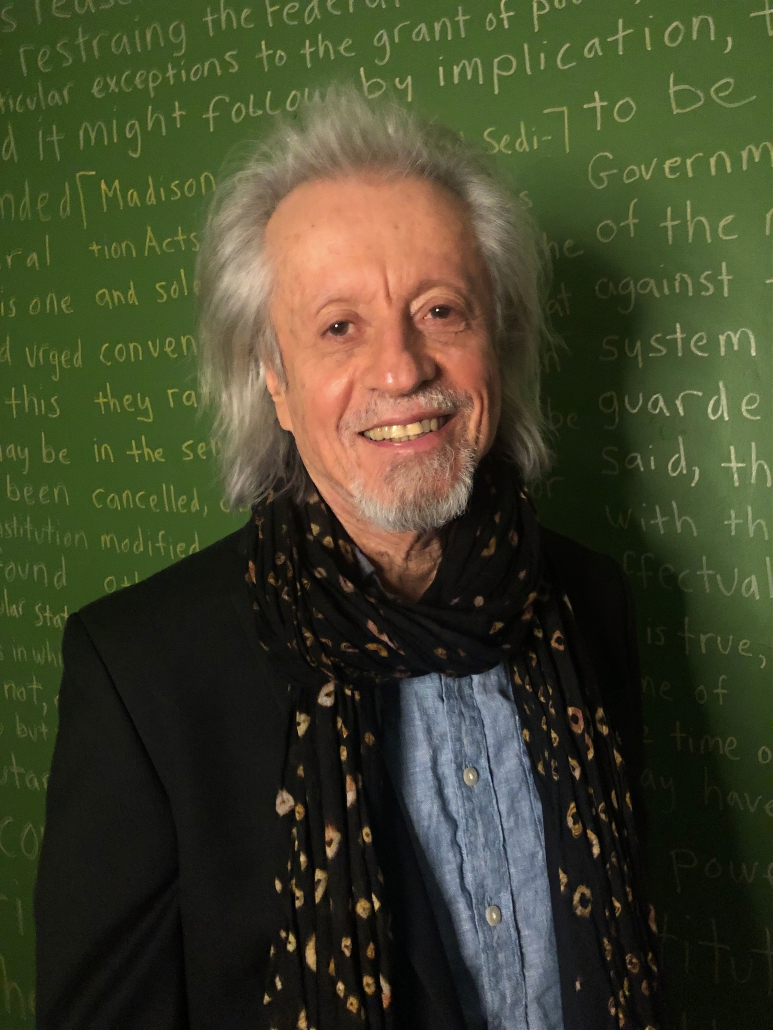

Paul Abramson, a UCLA professor of psychology who was hired as an expert by Caldwell’s legal team to assess the psychological harm Caldwell suffered, conducted 20 extensive interviews with Caldwell between 2015 and 2020, in addition to interviewing prison correctional officers and reviewing court hearings and decisions, depositions, psychological testing results and experts’ reports.

In a paper published in the peer-reviewed Wrongful Conviction Law Review, Abramson provides an overview of the case and a comprehensive psychological analysis detailing the devastating and ongoing effects of Caldwell’s wrongful conviction and imprisonment. He also examines the historically contentious relations between police and communities of color and asks why corrupt and abusive officers rarely face punishment for their actions.

Caldwell’s 1991 conviction was overturned on March 28, 2010. The San Francisco District Attorney’s Office dismissed the case, and Caldwell was released from prison in 2011. He settled his decade-long civil suit against the county and city of San Francisco, the police department and one SFPD officer just weeks before the scheduled start of the trial, and this month, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors approved an $8 million payout to Caldwell, who was 23 at the time of his conviction.

‘Appalling injustice’: The wrongful conviction of Caldwell

In January 1990, San Francisco Police Sgt. Kitt Crenshaw was among several officers who chased a group of young Black men who had allegedly been firing weapons at streetlights in the city’s Alemany public housing project. Caldwell was apprehended but not arrested. Caldwell alleged that Crenshaw physically abused him and threatened to kill him, and he filed a complaint against the officer with the city’s police watchdog agency.

About five months later, a man was shot to death in the Alemany projects. Crenshaw, who was not assigned to the homicide division, volunteered to search the projects for offenders and made Caldwell his primary subject, write Abramson and his co-author, Sienna Bland-Abramson, a UCLA undergraduate psychology major (and Abramson’s daughter) who worked on the case as a senior research analyst at two civil rights law firms.

On the strength of a dubious eyewitness claim and Crenshaw’s investigation notes, Caldwell was ultimately convicted of second-degree murder and two other charges and sentenced to 27 years to life in prison. Another man eventually confessed to the murder. Bland-Abramson concluded that San Francisco police officers had committed racial profiling, harassment and acts of corruption.

► Watch a video and read more on Caldwell’s case (Northern California Innocence Project)

Crenshaw, who retired from the San Francisco Police Department in 2011 with the rank of commander, had 67 civilian complaints lodged against him over the course of his career but never faced repercussions for purportedly fabricating his notes to frame Caldwell for murder, Abramson and Bland-Abramson write.

Catastrophic suffering and profound distress

Caldwell endured catastrophic suffering, profound and overwhelming stress throughout his incarceration in various prisons, Abramson writes. How did Caldwell’s experiences affect him?

About 2 1/2 years after Caldwell entered the California prison system, he was brutally stabbed in the head, shoulder and chest by another inmate who used an improvised 6-inch-long knife made from a metal rod filed to a sharp point. At the time, he was an inmate at California State Prison, Sacramento, also known as New Folsom’s Level 4 Prison.

Caldwell said the stabbing changed his life. “I knew at that very moment I could be killed at any time, on any day,” he told Abramson.

Psychology professor Paul Abramson, who conducted 20 interviews with Caldwell over a five-year period, said the former inmate is suffering from complex PTSD.

A retired correctional officer, Chris Buckley, who knew and had supervised Caldwell while he was incarcerated in a Northern California maximum-security prison, told Abramson last year, “A Level 4 prison is like the worst neighborhood you could imagine. Something terrible always might happen. Besides all of the stabbings, there are so many sexual assaults. Fear of dying in prison is a legitimate concern.”

Caldwell routinely observed violent struggles and riots throughout his incarceration, and repeatedly saw lethal weapons in the possession of inmates. He never felt safe any time he walked outside his cell, always fearing for his life. His closest family members — his grandmother, mother and brother — all died while he was in prison. He was prohibited from attending their funerals and became suicidal, feeling he had nothing, and no one, to live for, Abramson and Bland-Abramson write.

“Being in prison was like going to war every day,” Caldwell told Abramson. “It’s only when I was in my cell at night that I felt I was safe. I was depressed every day in prison. I don’t sleep. I suffer every day. I can understand how someone would go postal. I wouldn’t do something like that, for my kids, for all kinds of reasons. But I can understand.”

Caldwell suffers from what is known as complex post-traumatic stress disorder — a form of deeply entrenched severe psychological distress also experienced by Holocaust survivors, prisoners of war and victims of childhood abuse, domestic abuse and torture — the result of having experienced sustained and repetitive agonizing events, Abramson said. Complex PTSD is often marked by rage and an unyielding depression, as in Caldwell’s case, according to Abramson.

“Mr. Caldwell could very well be an archetype for complex PTSD,” Abramson writes. “Maximum-security prisons maintain complete coercive control through 24-hour armed surveillance, locked cell blocks, 24-hour visibility of every aspect of a prisoner’s life, routine strip searches and thoroughly structured daily routines; all of which is encompassed within a fortress that is distinguished by outside perimeter barriers, and surrounded by razor wire with lethal electric fences designed to eliminate the possibility of escape.”

The many traumas Caldwell, now 54, experienced while in captivity imposed such an emotional burden on him that he disintegrated psychologically, Abramson writes, and the recent civil settlement provides no measure of relief from the deep and lasting anguish and rage that consume him — and likely will for the rest of his life.

Caldwell and Buckley, the former correctional officer, spoke with UCLA undergraduates in late September in an “Art and Trauma” honors collegium course that Abramson co-teaches.

Abramson and Bland-Abramson conclude that Caldwell was a victim of appalling injustice, which continues to disproportionately affect people of color in the United States. Recent research has shown that Black people in the U.S. are seven times more likely than white people to be wrongfully convicted of murder.

“Our hope,” the authors write, “is that by presenting this material, we can facilitate an understanding for, and empathy with, the trials and tribulations of victims of color who have suffered tremendously from police corruption and wrongful convictions. Until equal protection under the law is sustained unequivocally, restorative justice for people of color will be grievously foreshortened.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.