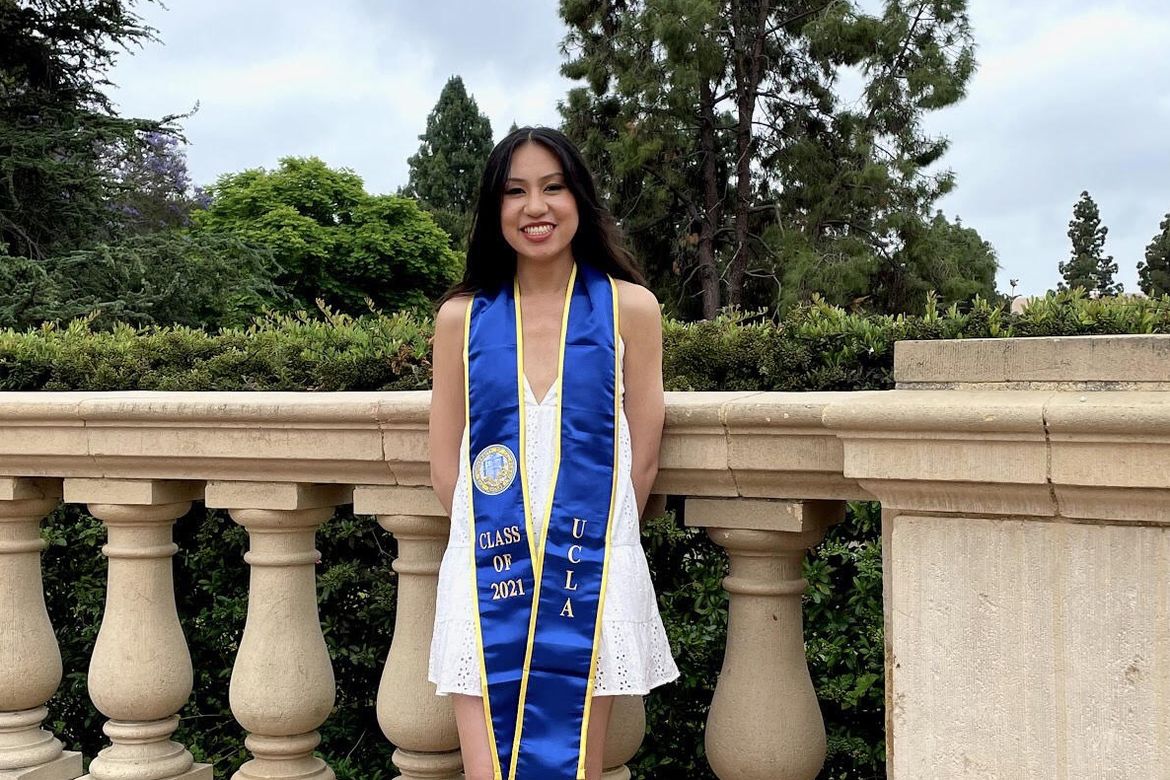

Graduating senior forged new connections to Vietnamese heritage through UCLA class

Anne Nguyen started observing the economic and emotional tolls of the pandemic before a lot of others.

Having grown up in a community of mostly Vietnamese immigrants, she knew families who owned nail salons, people who worked as nail techs and also was familiar with some of the health concerns given the exposure to chemicals in that industry. It wasn’t until she came to UCLA in 2017 that she realized the severity of some of the health problems associated with spending hours in a salon.

Then in March 2020, nail salon workers were being laid off even before shutdown orders because of the rapid decline in business after false reports that the virus was spreading in nail salons. Soon after there was the rise in anti-Asian racism.

“The impact on this community feels close to home,” said Nguyen, a soon-to-be UCLA graduate from San Jose, California, who is determined to help the broader immigrant community that raised her.

During her time at UCLA, Nguyen spent four years volunteering with the student-run Vietnamese Community Health organization, or VCH, which operates mostly in Orange County offering screenings for hypertension, blood glucose, cholesterol, as well as women’s health services like mammograms or OB-GYN consultations.

Nguyen and the group have also focused on offering connections to mental health providers who speak Vietnamese. She says the community, especially the elderly members, have historically stigmatized the use of mental health resources, but that these resources are invaluable to refugees and immigrants who are adjusting to a foreign culture and experiences.

“I think that my work with VCH was particularly meaningful to me because it introduced me to community-based medicine,” said Nguyen, who is on track to earn her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and a minor in Asian American studies. “I loved the focus that the organization had on educating their patients, as well as treating/screening them. It really helped me establish my service philosophy of giving communities the tools they need to commit to long-term change themselves.”

This past winter quarter, Nguyen’s desire to help Asian immigrants, took a more academic turn. She enrolled in a course put on by the Asian American studies department and the UCLA Center for Community Engagement called “Power to the People: Asian American Studies 140XP.”

The Center for Community Engagement supports community-engaged research, teaching and learning in partnership with communities and organizations throughout Los Angeles and beyond. This particular course was borne out of the hunger strike at San Francisco States University in the 60s, during which students demanded the school offer ethnic studies classes and that the school diversify its faculty and student body. This course, which has been taught at UCLA for seven years exposes students to different Asian American and Pacific Islander communities in greater Los Angeles and creates opportunities to work directly with those organizations.

During the course, Nguyen met with the instructor and her classmates two hours each week to discuss history and theory, and met virtually with community organizers, advocates and members of the nail salon industry through the California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative. The statewide, grassroots organization addresses health care, environmental factors, reproductive justice, and other social issues faced by low-income, immigrant and refugee women from Vietnam.

Dung Nguyen, program and outreach manager for the collaborative, supervised Anne Nguyen (no relation) and previous UCLA students who interned at the organization. Dung said there is nothing like working directly for an organization to bring social activism to life.

“Our student interns often reflect how civic engagement, advocacy, community organizations and collective power in a text book are very different than seeing this all play out in reality,” Dung Nguyen said.

Nguyen and another student phone banked to raise awareness about two bills in the state legislature — assembly bills 15 and 16, which were intended to protect tenants from being evicted during the pandemic and beyond. The pair created packages of Lunar New Year cards and masks for members of the nail salon collaborative to reinforce social bonds with the group during the isolation of the pandemic. They ran a small fundraiser to support nail salon workers who lost income during the pandemic and couldn’t meet their most basic needs. They also conducted a survey to see which members had been vaccinated, and then helped women get vaccination appointments so they could return to work safely.

“I did not expect to take a class like this when I came to UCLA since I never thought of volunteering/interning as something you can structure into a curriculum,” Nguyen said. “Every organization had a different method of organizing to best fit their communities and this class really reinforced that this was valid. The class gave me a greater appreciation for all the thought that went into the creation and continuation of the nail salon collaborative and all of the other class partners.”

Community organizer and course lecturer Sophia Cheng said that all the community partners tend to see themselves as part of the ethnic studies movement that started in the 1960s.

Cheng, who is the primary liaison for all the organizations, pushes students to go beyond critiquing, analyzing and dissecting situations, instead asking them to come up with real solutions to real issues. She said that she’s not trying to train every student to join the non-profit sector; there aren’t enough jobs in the Asian American nonprofit sector. Instead, Cheng focuses on different ways students can serve their communities in whatever career path they take.

Nguyen’s trajectory continues to be influenced by Cheng’s approach.

“I want to be a doctor, and I am focused on community health,” Nguyen said. “The course taught me to be more cognizant of cultural fit when it comes to health care, and other needs. A lot of Asian American and Pacific Islander patients might not trust or have resources like in typical western health care. The older generation also might not trust the younger generation. I’m using approaches from class to figure out how to approach medicine and how to help people, from the place where they are. I try to figure out what are the needs of the people, how can I serve them, and help them strengthen what they have to improve themselves.”

This article, written by Elizabeth Kivowitz, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.