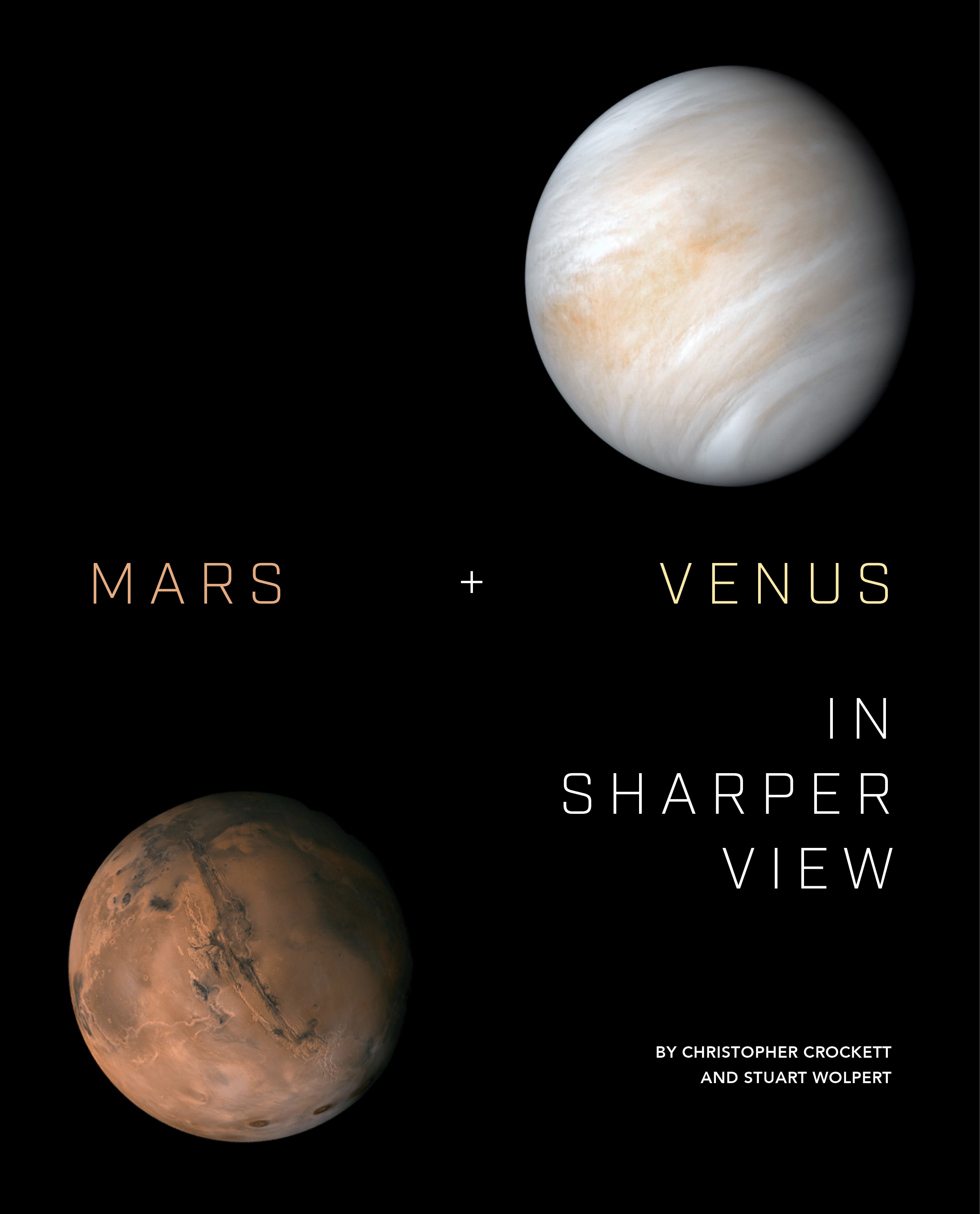

New Insights into Mars and Venus

By Christopher Crockett and Stuart Wolpert

David Paige is deputy principal investigator of Radar Imager for Mars’ Subsurface Experiment, or RIMFAX, one of seven instruments on NASA’s Perseverance rover.

About the size of a car, the Perseverance rover landed on Mars on Feb. 18. Over the next two years it will explore Jezero Crater in Mars’ northern hemisphere for signs of ancient life and new clues about the planet’s climate and geology.

Among other tasks, Perseverance will collect rock and soil samples in tubes that a later spacecraft will bring back to Earth. The experiments will lay the groundwork for future human and robotic exploration of Mars. RIMFAX will probe beneath the planet’s surface to study its geology in detail.

“Jezero Crater is a very interesting location on Mars because it looks like there was once a lake inside the crater, and that a river flowed into the lake and deposited sediments in a delta,” Paige said. “We plan to explore the delta to learn more about Mars’ climate history, and maybe something about ancient Martian life. What we’ll be able to see once we start roving and what we will actually learn is anybody’s guess.”

RIMFAX will provide a highly detailed view of subsurface structures and help find clues to past environments on Mars, including those that may have provided the conditions necessary for sup-porting life, he said.

Paige emphasized that RIMFAX is an experiment. “We’ve never tried using a ground-penetrating radar on Mars before, so we can’t really predict what types of subsurface structures we might be able to see. But we have done some fairly extensive field testing of RIMFAX on Earth to learn how to use it and how to interpret the data. Here, ground-penetrating radars can be very useful for clarifying subsurface geology.”

Is he hopeful of finding water, or evidence of water, beneath the planet’s surface?

“There are all kinds of evidence for past liquid water all over Mars,” Paige said. “At Jezero, there must have been a lot of water at some point, but we don’t expect that the ground beneath the rover will still be wet. Mars today is a very cold place, and any water in the shallow subsurface should be frozen at Jezero. What we’re interested in finding are geologic features that wouldn’t be expected to form under present climatic conditions, as those would be especially interesting targets to search for signs of past life.”

UCLA College graduate students Max Parks and Tyler Powell in Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences are part of the science team, and Mark Nasielski, a UCLA graduate student in electrical engineering, is part of the operations team.

VENUS IS AN ENIGMA

Venus is the planet next door yet reveals little about itself. An opaque blanket of clouds smothers a harsh landscape pelted by acid rain and baked at temperatures that can liquify lead.

Now, new observations from the safety of Earth are lifting the veil on some of Venus’ most basic properties. By repeatedly bouncing radar off the planet’s surface over the last 15 years, a UCLA-led team has pinned down the precise length of a day on Venus, the tilt of its axis and the size of its core — findings published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“Venus is our sister planet, and yet these fundamental properties have remained unknown,” said professor Jean-Luc Margot, who led the research.

Earth and Venus have a lot in common: Both are rocky planets and have nearly the same size, mass and density. And yet they evolved along wildly different paths. Fundamentals such as how many hours are in a Venusian day provide critical data for understanding the divergent histories of these neighboring worlds.

Changes in Venus’ spin and orientation reveal how mass is spread out within. Knowledge of its internal structure, in turn, fuels insight into the planet’s formation, its volcanic history and how time has altered the surface. Plus, without precise data on how the planet spins, any future landing attempts could be off by as much as 30 kilometers.

The new radar measurements show that an average day on Venus lasts 243.0226 Earth days — roughly two-thirds of an Earth year. What’s more, the rotation rate of Venus is always changing: A value measured at one time will be a bit larger or smaller than a previous value. The team estimated the length of a day from each of the individual measurements, and they observed differences of at least 20 minutes.

Venus’ heavy atmosphere is likely to blame for the variation.

The UCLA-led team also reports that Venus tips to one side by precisely 2.6392 degrees (Earth is tilted by about 23 degrees), an improvement on the precision of previous estimates by a factor of 10. The repeated radar measurements further revealed the glacial rate at which the orientation of Venus’ spin axis changes, much like a spinning top. On Earth, this “precession” takes about 26,000 years to cycle around once. Venus needs a little longer: about 29,000 years.

The team has turned its sights on Jupiter’s moons Europa and Ganymede. Many researchers strongly suspect that Europa hides a liquid water ocean beneath a thick shell of ice. Ground-based radar measurements could fortify the case for an ocean and reveal the thickness of the ice shell.

And the team will continue bouncing radar off Venus. With each radio echo, the veil over Venus lifts a little bit more, bringing our sister planet into ever sharper view.

This research was supported by NASA, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the National Science Foundation.

Back to UCLA College Magazine page