New digital exhibit explores Jewish history in Boyle Heights

In the 1930s, the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights had the highest concentration of Jewish people west of the Mississippi. There were approximately 10,000 Jewish households in the area, which was about a third of Los Angeles’ Jewish population. But Boyle Heights was also one of the most diverse neighborhoods — home to many Mexican, Japanese, Armenian/Turkish, Italian, Russian and African American families.

The Jewish Histories in Multiethnic Boyle Heights exhibit gathers archival materials, artifacts and personal stories to explore the rich history of the Jewish community in this neighborhood, while also observing how those experiences coincided with the other diasporic communities that lived there.

“The history of this neighborhood really lives on in people’s hearts and minds … and basements,” said Caroline Luce, chief curator and associate director of the UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies.

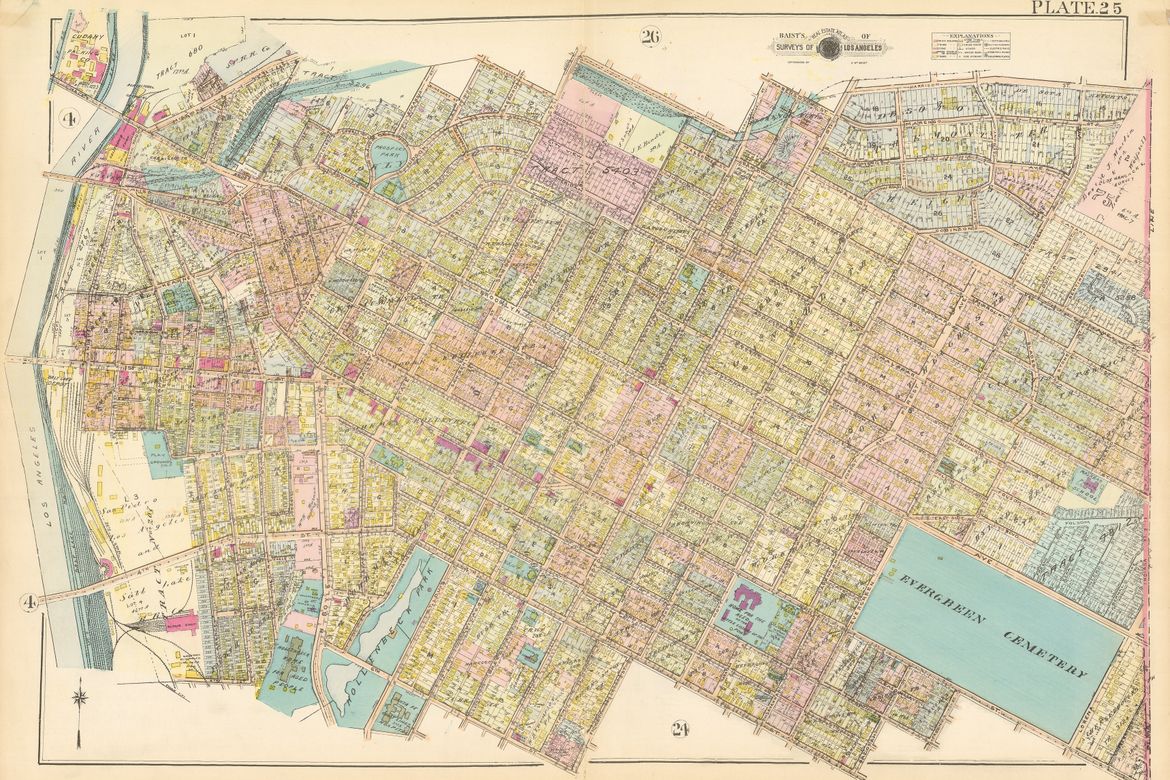

The Boyle Heights exhibit is part of the Mapping Jewish L.A. project, a decadelong partnership between the Leve Center, UCLA Library and Special Collections, University of Southern California and other community archives. Through digital tools and multimedia technologies, the project enables a broader understanding of the complex histories of the Jewish community in Los Angeles.

“Like all of our projects at Mapping Jewish L.A., this exhibit aims to open a new public space for the discussion and discovery of L.A.’s kaleidoscopic history,” Luce said. “It serves as a new mode of remembrance, one that is collaborative and inclusive, that nurtures intergenerational and interethnic understanding, and that strengthens the ties between UCLA and the local community.”

Below is a preview of what you will find in the extensive digital exhibit, which covers many aspects of Jewish life in Boyle Heights, from education to cars and community centers.

Mollie Silverman (left) and friends in front of an automobile on Malabar Street in Boyle Heights, ca. 1918. (Photo Credit: Shades of L.A. Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

The first automobile to ever drive through Los Angeles did so through the streets of Boyle Heights on May 30, 1897. J. Philip Erie, a New York civil engineer, spent $30,000 to design, invent and build the first gasoline-propelled automobile carriage west of the Mississippi River. The drive started in downtown Los Angeles and ended at Erie’s home near Hollenbeck Park.

By the 1930s and ’40s, cars were necessary to access jobs that were located beyond the downtown industrial zone. After World War II, as freeway construction in and around the neighborhood began, Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans and Jews formed social clubs revolving around the automobile. These clubs would sponsor food and toy drives, car washes and community events in their neighborhood.

Read more about the history of automobiles in Boyle Heights.

Students of the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order Yiddish school perform their annual Purim play at the Cooperative Center in 1938. (Photo Credit: Shades of L.A. Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

In the early 1920s, members of the Arbeter Ring (Workers Circle), a proletarian fraternal organization, and Jewish activists affiliated with the Cooperative Consumers League, a left-leaning cooperative buying club, created a place where Boyle Heights’ multiethnic residents could socialize, learn and organize. They called it the Cooperative Center, a large, three-story building near the corner of Brooklyn Avenue and Mott Street. There were several meeting rooms on the top floor; a large ballroom for lectures, rallies and social events in the middle; and a bakery and café on the ground floor. The building operated on a cooperative basis: Shareholder members voted democratically on administrative decisions, and union labor was employed throughout the building.

The Cooperative Center became a hub for neighborhood-based organizations and an important site of political organizing and social activities. The center hosted lectures by Upton Sinclair; organized meetings for the carpenters, furniture makers and bakers unions; and held social activities that blended consciousness raising, interethnic mingling and fundraising. Several unions and cultural organizations rented space there, as did the local branches of the International Workers Order, a left-leaning fraternal organization that offered low-cost insurance to its members regardless of race, religion or creed.

Read more about the history of the Cooperative Center.

This photo appeared in “Who’s Who in sponsoring the Mount Sinai Hospital and Clinic, Annual Directory 1945.” (Photo Credit: Associated Organizations of Los Angeles)

The origins of Mt. Sinai Hospital — part of today’s Cedars-Sinai Medical Center — can be traced to the 1918 pandemic, when a group of Jewish Angelenos provided kindness and comfort to the sick. The effort reflected the Jewish value of bikur cholim (“visiting the sick”) — a traditional halakhic (Jewish religious law) principle that deems alleviating the suffering of the ill and offering prayers on their behalf to be an important mitzvah (commandment or good deed). In 1920, the group established the Bikur Cholim Society and purchased a small home in Boyle Heights to provide round-the-clock care for the neighborhood’s “incurables.”

By the end of the decade, the Bikur Cholim Society moved into a large building on Bonnie Beach Place. Known as the Mt. Sinai Home for Chronic Invalids, the facility, which featured a kosher kitchen and small prayer room, provided a space for observant Jewish patients to receive care.

Read more about the history of Mt. Sinai Hospital.

The Japanese Hospital, located at First and Fickett streets in Boyle Heights, in 1929. (Photo Credit: Japanese American National Museum)

Similar to the community spirit of Mt. Sinai Hospital, the former Japanese Hospital, located at First and Fickett streets in Boyle Heights, reflects how Japanese Americans took care of others in their community. In the early 1900s, public health officials often associated disease with recent immigrants and certain ethnic groups, and they used race to determine how to administer public health programs. As a result, Japanese immigrants, who were viewed as the least able to assimilate compared to other immigrant groups, didn’t have access to mainstream health care.

To meet the needs of their community, Japanese medical professionals established the Turner Street Hospital in Little Tokyo in 1913. But as the Japanese American community continued to grow, so did the need for more substantive medical care. Five immigrant Japanese doctors decided to build a larger hospital with state-of-the art surgical facilities, and the Japanese Hospital opened on Dec. 1, 1929.

“Both institutions are examples of how immigrant residents in Boyle Heights worked together to meet the basic needs of the most vulnerable, including health care, shelter and child care,” Luce said. “By highlighting these overlapping patterns of community organization, we hope the exhibit illuminates the intersecting histories of the many diasporas that converged in Boyle Heights.”

Read more about the history of the Japanese Hospital.

The original building at 420 N. Soto St., which housed the folkshul, ca. 1922. (Photo Credit: Zunland, vol. 4 (1925))

In 1908, a group of Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe founded Los Angeles’ first Yiddish organization, the National-Radical Club. Among its primary goals was establishing a Yiddish school, so Jewish parents could supplement their children’s public school education. Advocates for the school included Dr. Leo Blass (née Lieb Isaac Shilmovich), whose devotion to Yiddish culture was legendary. Blass and members of the National-Radical Club began teaching classes at a private home near Michigan Avenue and Breed Street.

In 1920, Blass and the school board launched a fundraising drive to purchase a house at 420 N. Soto St., where the school would become a Yiddish cultural center and organizing space. The new center, known as the folkshul (“people’s school”), opened the following year with 120 students. In addition to being a Yiddish school, the folkshul quickly became a popular destination for organizations and events, hosting meetings of local Jewish unions, fundraisers and bazaars, and an annual Hasidism ball.

Read more about the history of the folkshul.

From left: The Soto-Michigan JCC featured a playground where children could enjoy a jungle gym, swing sets and pingpong tables. Both photos were taken by Julius Shulman in 1938. (Photo Credit: Julius Shulman Photography Archive, © J. Paul Getty Trust.)

The Soto-Michigan JCC’s three-story facility featured a lounge, game room and clubroom on the first floor and locker rooms in the basement. But the facility’s most popular feature was the Stebbins playground, where there was a jungle gym, volleyball and basketball courts, swing sets and pingpong tables. As many as 1,000 people regularly visited the Soto-Michigan JCC just to use the playground, in addition to the 2,300 children and adults who used the meeting rooms and auditoriums every week.

Read more about the history of the Soto-Michigan JCC.

As a complement to the Jewish Histories in Multiethnic Boyle Heights digital exhibit, there’s also a physical exhibit currently on display at the Boyle Heights History Studios, featuring materials that can’t be viewed online.

In addition, Holocaust Museum L.A. will host a discussion about the digital exhibit with Luce on May 26 at 11 a.m. Register for the event.

Luce will also discuss the project with USC professor George Sanchez on June 9. Details to follow at levecenter.ucla.edu.

This article, written by Cheryl Cheng, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.