UCLA students touch space with a microgravity experiment

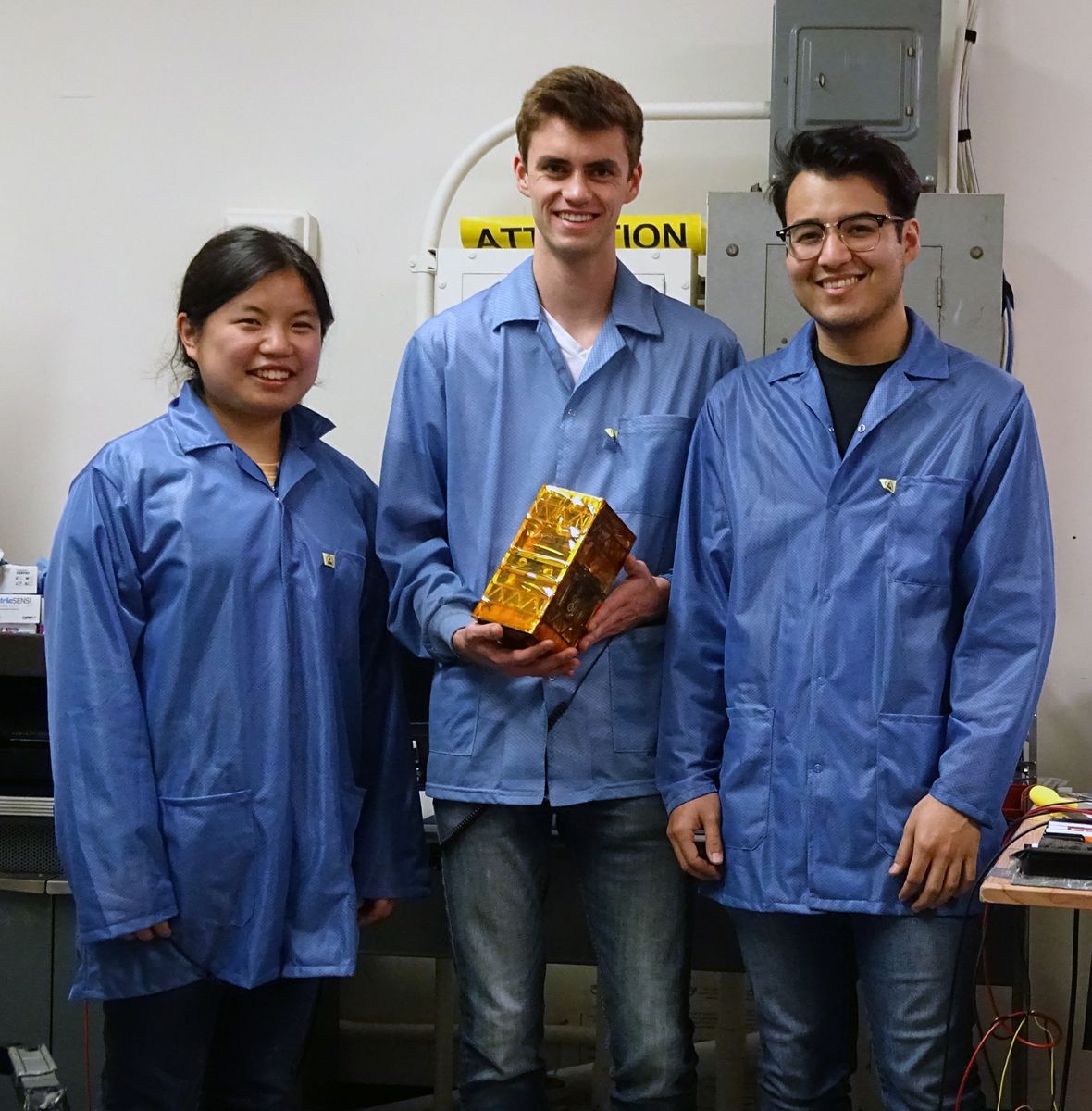

Bruin Space team members Chloe Liau, Andrew Evans, and Alexander Gonzalez holding their final flight model. Credit: Andrew Evans/Bruin Space

Magnetic pump built by Bruin Space launches on Blue Origin reusable rocket

It took only 10 minutes and a ride aboard the Blue Origin New Shepard reusable rocket for 11 students in the Bruin Spacecraft Group to make history.

At 6:32 a.m. on May 2, their experimental pump designed for use in zero-gravity environments, named “Blue Dawn,” completed its flight into a low-Earth orbit and freefall — thereby becoming the first space payload developed and built entirely by a UCLA student group.

“The goal was to see if we could design an efficient fluid pump without any moving parts to work in zero-gravity, which has never been done before,” said Alexander Gonzalez, fourth-year physics major and undergrad science lead on the project. Such a low-maintenance pump would be ideal for moving various liquids on the International Space Station, and could reduce the risk of motorized pump failures for rovers and even future bases on the moon or Mars.

The New Shepard rocket roared into the deep blue West Texas sky, ferrying a suite of 38 separate microgravity research experiments, including two built by student groups at UCLA and Case Western Reserve University.

For Blue Dawn, the UCLA team had to design a system containing the fluid, pump tubing, magnets and electronics in a custom aluminum frame that was about the size of a football and with a maximum weight of one pound.

Work began on the project in fall 2017. After designing it, the team of 11 students from several majors then manufactured and tested the pump entirely on campus. The Bruin Spacecraft Group, known as Bruin Space, secured primary funding for their project in 2017 by winning a grant from the American Society for Gravitational and Space Research Ken Souza Spaceflight Competition.

“It’s super exciting to directly apply the knowledge we gained in classes and actually build something that went into space,” said Andrew Evans, a third-year majoring in mechanical and aerospace engineering and who served as chief engineer. He stressed the value of hands-on team experience gained in such projects.

“That’s what Bruin Space is all about, solving real science questions while giving students an opportunity to fulfill their dreams of spaceflight,” Evans said.

To be judged a success, Blue Dawn had to operate fully autonomously during its 10-minute flight and freefall back to Earth. Once the capsule chutes deployed and it touched down softly in the desert, Chloe Liau, fourth-year mechanical and aerospace engineering student and structure/fabrication lead, breathed a sigh of relief.

“Seeing all our hard work pay off with a perfect launch and landing, it was nothing short of amazing,” Liau said. “But we still have a job to finish.”

The payload and flight data will be returned to UCLA this week, so that the team can analyze the pump’s performance in microgravity. They expect the flow in space to be more efficient compared to its performance in ground tests under the influence of gravity.

The team plans to publish the results of this first study and present at conferences, giving these students the experience of seeing a space mission end-to-end.

Team members said that it would not have been possible without the expert guidance of two geophysics and space physics Ph.D. students from the UCLA Department of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences: science advisor Emily Hawkins and project manager Lydia Bingley. The group was also supported by Richard Wirz, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering in the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering, and Chris Russell, professor of Earth, planetary and space sciences, whose prototyping lab facilities were used to build and test Blue Dawn.

What’s next for Bruin Space?

“We have several other exciting projects in development, from weather balloons and rocket campaigns, to designing a microsatellite propulsion system,” Evans said. “We are always looking for new members, check out our website at BruinSpace.com to learn more.”

This article originally appeared on the UCLA Newsroom.